New Jersey is the most densely populated state in the nation. Nonetheless over one-third of our land is preserved—1.5 million acres—by local governments, land trusts, Green Acres, NJ Wildlife Management Areas, state parks, Farmland Preservation, and the like. Citizens have always placed a priority on preservation, consistently voting for open space funding.

This undeveloped space provides a lot of habitat for wildlife to utilize, but the fragmentation created by urbanization and roads presents problems because animals need to move through the landscape for the basics—food, shelter, mates, genetic diversity, and resources. Animals often need various kinds of habitats at different life stages or seasons. Their forage needs can change during the year as well. Moving from one habitat to another while passing through unsuitable areas presents challenges and perils.

New Jersey has instituted an initiative to provide greater connectivity called Connecting Habitat Across New Jersey or simply CHANJ, pronounced “change.” We are clearly not the only state that’s conceived that a “change” needs to be made to our landscapes in order to help terrestrial animals move along safe corridors. At least half of our nation’s states have connectivity plans that try to create safe corridors for animals to move within and from one “core habitat” to another.

To accomplish safe corridors, protected space can be connected by adding to preserved lands. CHANJ focuses on safeguarding or improving habitats and achieving safer road crossings. It provides insight into what spaces should be prioritized for protection. NJ DEP Division of Fish and Wildlife is the organization leading the effort, but partners are a must to accomplish improved habitat connectivity.

CHANJ’s success relies on lots of expertise and cooperation. The people involved in the initiative normally fall into the broad categories of natural resource managers, transportation planners, conservationists, and researchers.

New Jersey utilizes five Landscape Regions to develop its Wildlife Action Plan. These are primarily based on physiographic areas within the state—Skylands, Piedmont Plains, Delaware Bay, Atlantic Coastal, and Pinelands. A huge number of overlay maps show a vast diversity of information—forest types, wetland types, endangered species, common species, vernal ponds, streams, rivers, lakes, roads, urbanization… you name it; if it is a habitat type it’s mapped.

The CHANJ project used several of these mapping layers to define “core habitats,” which are patches of primarily natural land areas. Then biologists and geographic information system specialists (GIS) studied adjacent habitat with potential for wildlife movement between “core habitats.” Each connection or corridor is rated in its potential for wildlife passage on a scale of 1–5, one being the easiest to traverse and five being more difficult. This allows wildlife managers opportunities to identify connections and to select priority CHANJ projects.

CHANJ makes use of two major components, mapping and a guidance document. The map shows the connective opportunities and the guidance document offers management practices that can be implemented on site to help animals navigate more safely. The CHANJ map is not a secret document; in fact people are encouraged to study these layers of maps for opportunities to help support safe passage. The teams of people who can make a difference are as a diverse as the habitats.

Roadways present the most challenging crossing. Maybe you have seen “guidebooks” identifying road kill, but the dark-humored theme is seated in reality. On U.S. roadways millions of animals are killed each year. In New Jersey many deer accidents are not only fatal to deer but extremely dangerous for drivers.

Mortality is most obviously caused by vehicular/animal collisions, but some animals die as a result of the barriers used to prevent them from crossing roads Although fences can keep animals off the road, they can also have the reverse effect of forcing them to remain on the road side of that obstruction. Animals are often attracted to resources like food, spilled grain, or heat from basking on blacktop. Some, like red tail hawks, use roadside habitat to hunt, while others, like deer and rabbits, use it for browsing. In any event when animals cross roads there are endless perils for them.

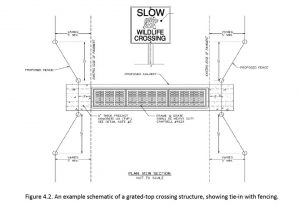

Culverts under the road are an excellent example of how safe passageways can be created under roadways. Thirteen states, including New Jersey, have been working in a regional partnership called North Atlantic Aquatic Connectivity Collaborative or NAACC, collecting data to assess road-stream crossings and rate their suitability for safe passage. Each is graded on a scale from no barrier, to significant barrier, to no crossing. Many sites still need to be surveyed and data accumulated. In 2019 about 269 of an estimated 9,128, or three percent, had been inventoried and scored for aquatic and terrestrial passability.

These data are included in the CHANJ mapping along with the ratings. The CHANJ Guidance Document cites as an example a culvert where stream edges lap its sides. This can be widened to offer dry passage along with water passage. Municipal, county, and state road designers can consider these new concepts when replacing old drains, especially if they’re located in an area where a wildlife connection would be valuable.

In addition to the opportunity to improve these culverts, the maps show where efforts are underway in New Jersey and where they are planned—road wildlife mitigation projects. You will notice that the Garden State Parkway has been working on a number of safer crossings. NJ Fish and Wildlife has a short video tutorial (12 minutes) demonstrating how to use the maps and a copy of the guidance document. The maps are fun and include a feature that can even hone in on where you are, so you can check out your digs. They display lots of data on the “core habitats”—their current rated connections, protected space, waterways, roads, watershed drainage lines, parcel data, county lines, vernal pools, and all kinds of other interesting factors.

Living in southern New Jersey you may have seen smaller passages used in conjunction with silt fences to assist diamondback terrapins to cross safely beneath the road, especially during breeding season when they move greater distances. NJ Fish and Wildlife also has specially designed under-the-road tunnels to assist turtles in central Jersey. It is equipped with a counter and at times with surveillance equipment to continually evaluate its effectiveness. These studies will allow biologists and engineers to make future design modifications if necessary.

I have greatly simplified the complexity of what is available to you using the CHANJ program. If this interests you, please look at the NJ Fish and Wildlife website to see the extent of this massive undertaking. Each of the projects is fascinating in and of itself. Connecting landscapes is the only hope we have in this urbanized landscape for animals to be protected, in order to maintain biodiversity and for the enjoyment of this and future generations.

Here at CU Maurice River we are continually teaching people about backyard habitat, which is one way that property owners can make their property part of that connectivity. You may be aware of entomologist Doug Tallamy’s writings where he explains how we can each become part of the nation’s largest collective national park if we simply make an effort by choosing native plants for our yards.

Beyond a moral obligation to the natural world, know that as living things we are all inter-related and our very survival depends upon being good stewards of the environment and of the creatures around us.

Sources

NJ Fish and Wildlife materials

CHANJ – Connecting Habitat Across NJ, Guidance Document

Forman and Alexander 1998

Website: chanj.nj.gov