Each family seems to have its traditional holiday stories, and for me the quintessential tale is one my mother used to tell about her childhood on Thanksgiving Day. She was the youngest of four children and the only one in her entire family not born in Spain. Yet she too made the voyage across the Atlantic to join her father who, like many other immigrants, had established a residence on the other side of the ocean ahead of a family who remained in Europe. My mother’s passage was made in her mother’s womb, initially to Cuba.

In the first half of the 20th century assimilation was a first priority for recent immigrants. My mother felt separated from her new country because she grew up in a Spanish-speaking household. Diversity was not celebrated like conformity. She was deeply embarrassed at being unable to speak English when she started grade school. Apparently she was the only child in her class who had no knowledge of America’s official language.

Holidays like Thanksgiving helped to define people as Americans, and the Gago family was very excited to celebrate all events that they associated with patriotism, feeling that they provided a connection to their new country and its people. In fact my mother always loved the national holidays. She cried tears of pride at firework displays and when the American flag passed at parades.

Patriotism defined my mom and influenced me. In grade school, when they spoke of our country as a melting pot, I swelled with pride over my mixed heritage.

Like many first-generation Americans my mom’s family struggled to make ends meet. They lived in downtown Pittsburgh, in a house with a small backyard where my grandparents had a garden. One year, months in advance of Thanksgiving, my grandfather purchased a poult, or young turkey. Someone named it. At this you may be shaking your head and rolling your eyes in that knowing way: “What were they thinking?”

I recently read on the internet that domestic turkeys make great pets and are quite docile; unfortunately that didn’t help theirs to avoid what was to become its inevitable fate. The family members all took turns feeding it, and then, when it was time for Thanksgiving dinner, my grandfather—Abuelito or simply “Lito”—played the dastardly role of executioner.

The Presidential pardoning of turkeys didn’t begin until Harry S. Truman’s term, so this poor fowl didn’t have a prayer or hope of recourse. He was a dead duck … or, well, you know. As my mother remembers it, her father looked quite pale, returning from the backyard with his feathered prize. Everyone was horrified.

When Mom would tell the story, I would always imagine the family’s collective faces when the main dish was delivered to the table. All of them had wide-set, saucer-shaped, deep brown eyes and ebony hair: Spanish eyes that could melt your heart, and my mother and her sister always looked a bit misty-eyed anyway.

The Gagos said grace. But instead of passing their plates for sides and the main dish they simply stared at the carcass. No one ate, and one by one they simply dismissed themselves from the table. Grandma and the girls sobbed. My grandfather swore off raising poultry ever again.

As an adult my mother would laugh and cry when she relayed the story of that Thanksgiving. Each Thanksgiving Day we would beg her for the tale about the Thanksgiving dinner that never was: “Mom, tell us about the year Lito raised a turkey and no one ate.”

She would begin, “Oh my, that was a big mistake. We never raised another turkey.”

So where did the domesticated turkey of today originate? From DNA analysis we actually have great insight into the origins.

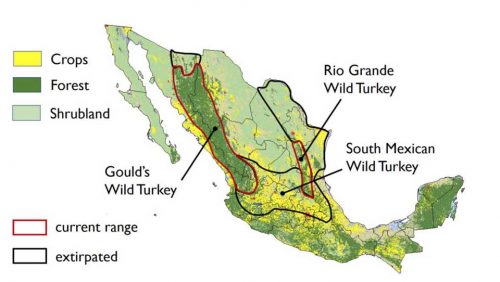

In previous articles we discussed the six subspecies of wild turkeys in the Americas: Eastern, Osceola, Rio Grande, Merriam’s, Gould’s, and the Ocellated. There is yet another subspecies, thought to be extinct but originating in Central America: the South Mexican turkey in Spanish guajolote (translated to “old monster or big monster referring to the turkey’s massive size). Sightings thus far have been contested. It is this species that, via genetic studies and archeology, is known to have been domesticated nearly 2,000 years ago.

Mitochondrial DNA (female) analysis of 149 turkey bones and fossilized dung from 38 archeological sites dating from 200 BC to AD 1800 revealed a unique breed in pre-colonial southwestern United States and southern Mexico. The analysis proved that Europeans were not responsible for domesticating turkeys. The DNA further revealed intensive human selection and breeding of wild turkeys in order to develop the domestic strain. The scientists who conducted these analyses concluded that Native Americans had employed sophisticated animal breeding practices.

We also know that exploration of Mexico is what exported the fowl to the Levant, a regional name for portions of some Middle Eastern countries—Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and yes, Turkey. The fowl were then brought via Spain to Britain, where they were called “turkeys.”

You might ask, “How does a wild animal become domesticated?” The simple answer is through many years of selective breeding. By way of example today’s dog would be the result of breeding individuals with desirable traits over thousands of years (an estimated 11,000 to 33,000 years).

In the 1950s Soviet scientist Dmitri Belyaev bred silver foxes that displayed more docile tendencies to one another. By selectively breeding the friendliest ones over 10 generations, along with tameness, their coloration and other behaviors evolved as well. This is referred to as domestication syndrome, although the outcomes were contested in 2018 by a newer study. While there is not complete confidence in the syndrome, it is not entirely discounted.

The mitochondrial DNA studies of 2010 concluded that all domestic turkeys today originate from tamed Aztec lineages in “South Mexico.”

Bi* *ologist Joe Smith, PhD has written about how a different North American domestic species came into play at one point in time but is no longer part of the domestic stock. He noted, “Anasazi-bred domestic turkeys from the Four Corners region had their roots in the Eastern and Rio Grande subspecies. Today there is no trace left of this second domestic breed. It was once thought that the Merriam’s subspecies might be a feral form of the Anasazi type, but the genetic evidence doesn’t support this idea.”

So what happened to the South Mexican subspecies, which was the forerunner of our domesticated bird? Dr. Smith suggests that intensive agriculture may eventually have led to its demise, since turkeys are reliant on field and forest habitat.

But with each bite of Thanksgiving turkey, know that genetically the guajolote is still around. n

Postscript: After writing this story I called my older sister to check her recollections. She assured me that the traditional holiday tale is about Easter and a lamb. Furthermore, she says my grandfather bought my mother a fox terrier to help her overcome her grief. This will now go down as a great family holiday dispute. Meanwhile we have agreed that both of us are right, or I have at least declared that I am never wrong. So, guess what the 2023 Easter story is going to be about! Let’s see, I have visions of bighorn, Dall, and Stone sheep.

* * *

Sources:

Daly, Natasha (2019) “Domesticated Animals, Explained,” National Geographic.

Howell, S. N., & Webb, S. (1995) A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America.

Makowski, Emily (2019) “Exploring Life, Inspiring Innovation,” The Scientist.

Smith, Joe (November 2017) “Tracing the Origins of the Domestic Turkey,” Cool Green Science.

Speller, C.F., Kemp, B.M., etal., (2010) “Ancient mitochondrial DNA analysis reveals complexity of indigenous North American turkey domestication.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107, 2807–2812.