Last month I was leading a woodpecker interpretative walk at Peaslee Wildlife Management Area. One of our participants mentioned a spot where he and his wife often see red-headed woodpeckers, so I suggested we caravan to the location.

On the way the second car in line pulled over, causing a strange configuration of people following suit. I was baffled about why we were no longer following the lead car, which had reversed back to the rest of us. The second driver was Tom, who said, “Have you ever taken notice of these ants?,” as he pointed to a large conical mound on the roadside.

“Hmmm, I think I’ve noticed these uniform grains as I looked at the foot-high mound,” I replied. “What are they?”

With a wry smile Tom replied, “Allegheny mound ants. I think the Coastal Heritage Trail interpretative board features them.”

“Really,” I giggled, acknowledging the obvious; I had not read the board at the entrance road off Hesstown Road. One would think a trip leader might do this before leading a walk on a trail, although that is not to say I did not prepare but rather to acknowledge that I am often hyper-focused on my own agenda.

A few participants laughed, looked at me, and said, “I see a story coming.” Ah, expectations.

In retrospect I remember seeing these ants before while on a botany trek with Gerry Moore, but I didn’t recall identifying them or knowing anything about them. Gerry pointed out the reach of neighboring mounds, and I believe we were in the vicinity of Bennett’s Mill, contiguous with Peaslee.

My subsequent research led me to a treasure trove of extension service fact sheets. These rather large red and black ants are repeatedly maligned by extension services—state universities and colleges given the task of helping agricultural producers in each state. And as one would expect, extermination companies are among those also in favor of elimination. However the University of Maine extension information was out of step with the other extension fact sheets that I reviewed, referring to them as beneficial insects.

As we discuss their propensities you will begin to understand their history of persecution by property owners. Then we’ll explore an advantageous aspect.

These mounds are designed to be incubators for the queens’ eggs and larvae; note the apostrophe. It is unusual for ants in a colony to serve more than one queen but this species has several; it practices polygyny meaning “many women.”

The mounds can be very large. The one we viewed at Peaslee was about one foot high and three feet across. The depth of tunnels beneath these hills may extend three feet. The circumference of an Allegheny mound ant’s hill can encompass a much larger area—three to nine feet in diameter. One source suggests sizes of 15 to 18 feet and three and a half feet of mound height.

But its reach far exceeds the obvious knoll. In order to make their nursery/home, this incubator needs sun. The ants inject formic acid into plants and trees, all around the stem or trunk, which kills the vegetation in the surrounding area so that sunlight can penetrate to the forest’s floor and warm the nursery. The area in which vegetation is killed can encompass a 40- to 50-foot zone. And if the colony has divided and multiple mounds are present, vegetative destruction can be more widespread.

A 19-inch mound may harbor up to 250,000 residents.

I always enjoy reading Dr. Michael Paupp, from the University of Maryland’s Bug of the Week, in which he explores the marvels of the insect world. One of his articles featured this mound ant. In the spirit of investigation he allowed an Allegheny mound ant, Formica exsectoides, to bite him. Basically the mandibles of the ant penetrate the skin, then the abdomen of the ant curls under and injects venom. He described the bite as not all that painful, but the injection of the acid produced greater discomfort than the bite.

True to form I will take his word for it. I’m more than happy to learn from others’ experiences. Exterminators suggest taking a brush when dealing with their removal, to sweep them off clothing and skin. By the way, all ants can bite, but the resulting pain is not created equal. Take it from a person who 35 years ago decided to steal an orange from an orange grove, this being my first time seeing orange trees. How was I to know the grove was patrolled by fire ants? The result was a painful performance of the Watusi with a lot of expletives accenting the chorus. I suppose most farmers would find my fate well deserved!

On a night walk in Belize last month while looking for scorpions, spiders, owls, snakes, nightjars, and such I stopped to observe a kinkajou, just long enough to alert some fire ant soldiers to my presence. They send out pheromones to let others know a big bad intruder has invaded the colony. Within a few moments dozens of sentries were setting my ankles on fire. To which the guide repeated, “Watch out for the ants.” By the way, it is hard to watch a kinkajou in a tree and protect your feet at the same time.

Back to our Allegheny mound ants, each mound’s grains of sand are meticulously placed to magnify the sun’s rays, acting like a solar panel of sorts. Worker ants are continually arranging and rearranging these surface grains. The effect is as if a pile of uniformly sized sand particles were poured through a funnel onto the ground’s surface resulting in a perfectly formed cone.

Other workers have the task of collecting honeydew, or the secretions of plant-eating insects like aphids, for sugars. And some workers aggressively attack other insects for protein meals, and herein lies Maine’s divergence from the opinions of the other extension services that I perused.

The University of Maine describes workers as effectively controlling a vast number of pest species in pines, like sawfly, jack pine budworm, gypsy moth, and white pine-weevil. Among wild blueberries they prey upon caterpillars, beetles, treehoppers, leafhoppers, crickets, wasps, fireworms, flea beetle larvae, grasshoppers, and flies.

Their fact sheet concluded that “[t]he negative impacts of these colonies are the destruction of blueberry rhizomes and shoots in the immediate vicinity of the mound, but this is minor compared to the large benefit of pest control that is provided by the ants.” They go on to discourage spraying of insecticides because aphids are a necessary source of sugar for the ant, and aphids do little to no harm to the blueberry bushes. All of this gets considerably more technical than I have shared, but you get the main point.

Primarily these mounds are found in the wilds of southern New Jersey. But surely they are not something you would want in your child’s sandbox—which is unlike their natural habitat in any case. You likely wouldn’t want your child exposed to many of the extermination methods described online either.

So if perchance you see Allegheny mound ants on your property, I would advise you to look into their pros and cons before seeking an exterminator; after all, one man’s annoyance just may be another man’s asset.

Sources

“195 Beneficial Insect Series 1: Allegheny Mound Ants,” University of Maine Extension No. 2005.

“Mound Ants,” Howard Russell, Michigan State University Diagnostic Service – June 26, 2009.

University of Maryland Extension, Michael Raupp, “The Bug Guy,” 2016.

Numerous extermination service websites to gather information on extermination methods.

Fun Fact

Ants who secrete formic acid have a citrus taste. Once, in Costa Rica, the author was treated to the experience of ingesting one, and indeed it was lemony. But likely different species pack a different punch, so we don’t recommend eating Allegheny mound ants.

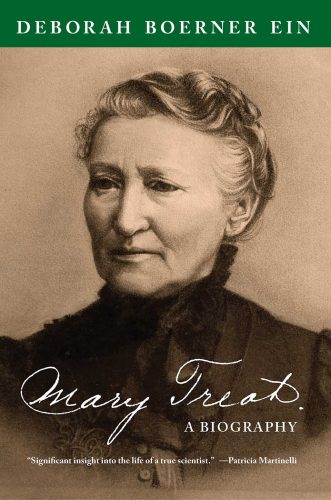

Ant Entomologist Mary Treat: Ahead of Her Time

Ant Entomologist Mary Treat: Ahead of Her Time

Early Vineland resident Mary Treat studied ant species along the Atlantic coastal plain, especially within the Jersey pine barrens. Read more about this esteemed naturalist’s life and research in the newly released book, Mary Treat: A Biography. Available at lulu.com, Amazon (amzn.to/3J8PZ0B) and other major booksellers.