True Lark

It is not uncommon for horned larks to attend the Millville Army Airfield Museum’s Airshow, perching upon runway lights to get a better view of the action. Photo: J. Morton Galetto

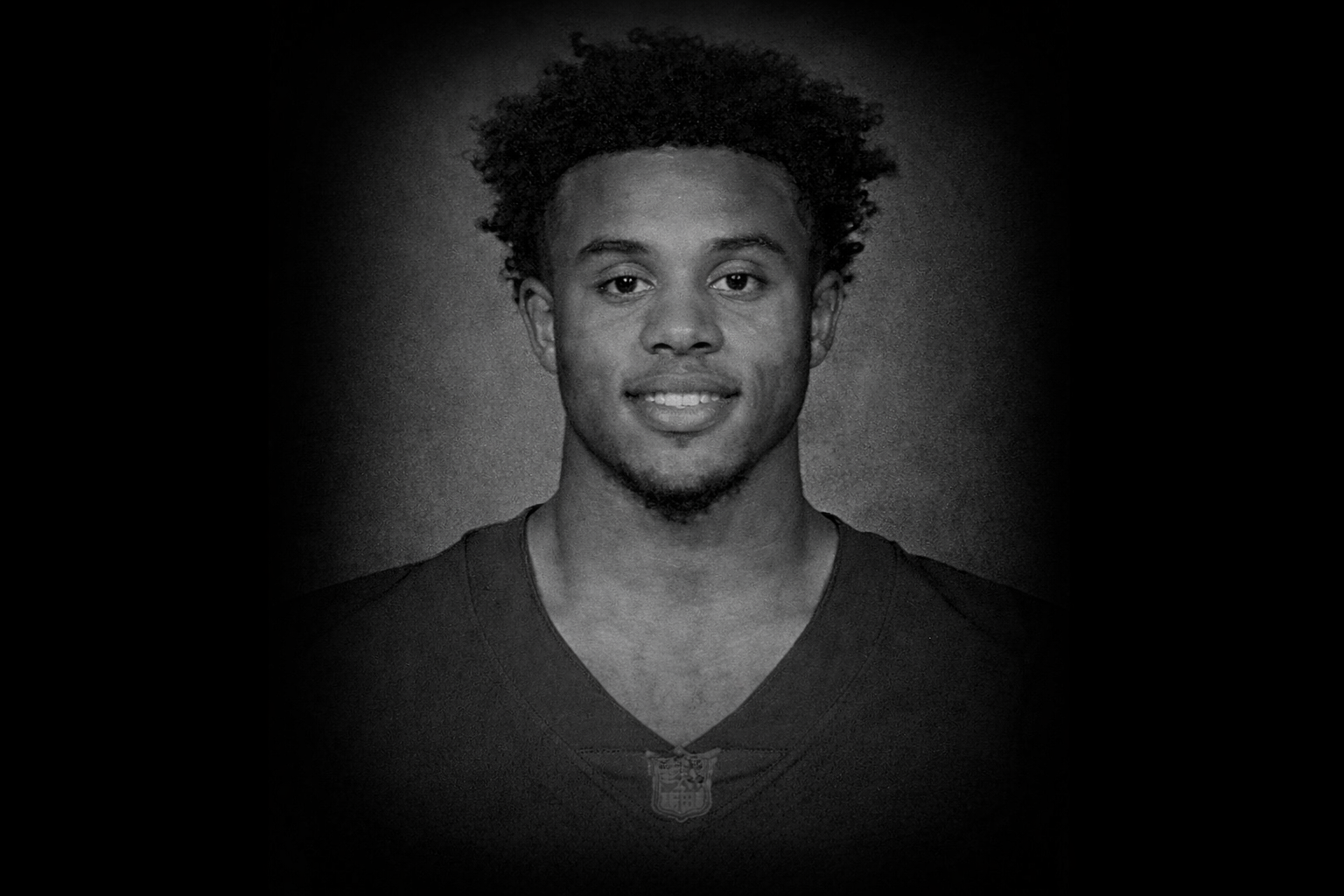

The male horned lark resembles Batman. The species is a year-round resident in our region. By Pam Hull, CU Maurice River

Before we continue, you may be shaking your head and saying “What about the meadowlark?” The meadow “lark” is lark in name only, based on its melodious, lark-like song and is actually in the blackbird family.

The only true lark in North America, the horned lark, is a bird of historic and beneficial distinction with a modern-day penchant for airports and other unusual grassland locations.

The horned lark’s name comes from two tiny feather tufts on each side of the male’s head. The male also sports a black mask which, along with the horns, gives him a fierce Batman-like look. The female has neither horns nor a mask but has similar buff and brown feathers.

The horned lark is a grain- and weed seed-eating bird whose numbers were once so vast that the USDA published a research report in 1905: “The Horned Larks and Their Relation to Agriculture.” The USDA was responding to the concerns of thousands of farmers with their millions of acres of wheat and other grains, as well as orchards and produce crops spanning farmlands in California to the Great Plains to the East Coast. The farmers feared that the horned larks would eat too much grain seed or too many beneficial insects, resulting in serious harm to crops and livelihoods! However, in the Letter of Transmittal for the Report dated September 1, 1905, Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson praises the species and the report itself likely put most farmers’ concerns to rest:

The horned lark bears some resemblance to one of our comic heroes. Photos: horned lark, Steve Gifford. Batman – William Tung

“The horned larks, though of small size, form an important group economically, because of their very general distribution, their great numbers and their food habits. As a result of the present investigation, it appears that, though the birds feed to some extent upon grain, the actual damage done is slight, because the grain eaten is mostly waste. On the other hand, the birds are shown to feed very largely upon insects and weed seeds, among which are some of the worst pests that the farmer has to contend with. The horned larks, therefore, should be classed among the species highly beneficial to agriculture.”

In fact, the entire publication honors the birds and their amazing eating habits and digestive tracts which, given their huge populations at that time, assisted farmers with weed and pest control. The report considers numerous species of beetles, bugs, weevils, caterpillars, and larvae that provide protein to the diet of horned larks. A few examples of destructive insects and the main targets of their destruction include chinch bug (wheat and grass), tarnished plant bug (all orchard crops and strawberries), larvae of the leaf-mining moth (nuts, fruits, and stored grain), flea beetles (cabbage, garden vegetables, strawberries, melons, sugar beets), click beetles and their larvae called wire worms (grain). Furthermore, a number of those same creatures are poisonous to other bird species.

When it comes to the weed and weed-seed part of their diet, horned larks’ digestive tracts can handle even the most deadly and destructive weeds and their seeds. Some of these include foxtails, the seeds of which can lodge in farm and working animals’ bodies, nostrils, lungs, etc. and can eventually cause death from infection if not found and treated; corn cockle, which grows in wheat fields and can cause death to cattle that ingest it along with wheat and to humans who have eaten wheat flour with corn cockle mixed in it; and pokeweed, which can be injurious to cattle. None of these and many other problematic weeds phase the horned lark with its muscular gizzard and ability to digest natural toxins.

For most of the year, the horned lark’s feathers provide excellent camouflage in turned and newly planted fields where they nest. Photo: Howard Patterson RIGHT: The horned lark is seen more often in winter although it is a year-round resident of southern New Jersey. Photo: Steve Gifford

About the size of an American robin, the horned lark has become a localized species in New Jersey and in other parts of the U.S. Here in New Jersey, its primary nesting areas lie in the Wallkill River Valley in Sussex County; parts of Warren, Salem, and Cumberland counties, and at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station in Ocean County. However, the species (and numerous subspecies that have come about from some very specific habitats/regions) is found in the Northern Hemisphere across the globe in African and Asian deserts, fields, beaches, tundra, stubbly grasslands, and on sparsely vegetated high mountain ranges, such as the Himalayas at elevations up to 13,000 feet. Horned larks are still holding their own worldwide—a species of Least Concern but they are Threatened in New Jersey and Threatened and Endangered in other parts of the U.S.

Even though it nests here and lives on the ground in New Jersey throughout the year, the horned lark is seen mostly in winter. Many people think of them as winter birds. During much of the year, their buff and brown feathers provide great camouflage. In the winter, however, when there is snow cover, they are more easily seen. Even without snow cover, horned larks follow the “safety in numbers” theory and form large flocks to feed in bare farm fields, airfields, and sometimes on roadsides. The local populations may be joined by northern breeding populations that move south for the winter. In these larger flocks other species, such as dark-eyed juncos and in some areas Lapland long spurs and possibly snow buntings, may also be congregating and feeding.

In their late winter/early spring breeding and nesting season, horned larks are solitary and are found in pairs or small flocks. An early nester before winter is over, in February or March, the female horned lark makes a depression in the ground and weaves a small nest of grasses and feathers in it. She builds a kind of patio of stones at the entrance to the nest and lays her clutch, averaging four eggs.The male and female both feed the chicks, which stay in the nest from nine to 17 days and then leave before they can fly. Unlike many other ground birds that hop, the horned lark walks or runs while it is searching for food. Horned larks return to the same nesting area/birthplace annually. Scientifically, this behavior is referred to as Philopatry or “love of homeland.”

Horned larks make a stony patio leading to their nesting site. Photo: Mike Allen, Lakehurst, NJ

Unlike a century ago when horned larks had farm fields for their nests and feeding opportunities practically anywhere in rural U.S., horned larks now find substitute habitats in the closely mown grass at airports. In South Jersey birders have seen them perched on runway lights or feeding in the grass at airfields in Millville, Woodbine, and Cape May. In addition, birders have spotted horned larks in the Sumner Avenue spray fields near Belleplain State Forest perched on the spray equipment. They love short grass; no higher than two inches, please. Horned larks have been known to abandon a nest site if the grass becomes too tall or too dense.

For those of you who want to spend time outdoors this winter, grab your binoculars and head for a nearby airport or very short grasslands to see if you are lucky enough to spot a horned lark.