Cultures Meet

Seabrook Farms, for some, offered a good jobs and housing; for others, economic exploitation and lost freedoms.

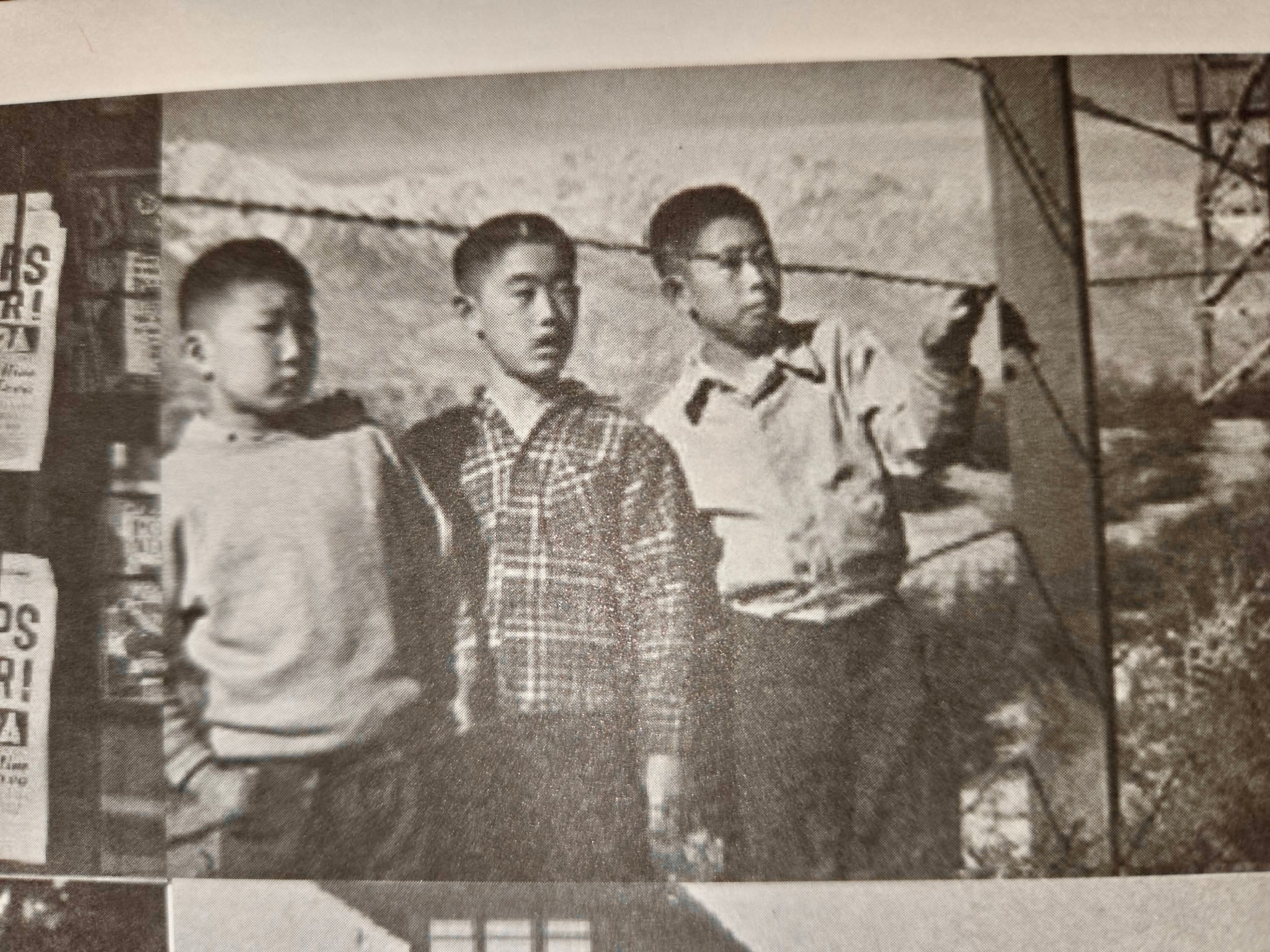

The arrival of Japanese Americans from the American West to Seabrook Farms in Upper Deerfield Township during World War II irrevocably linked the Cumberland County frozen food enterprise with the controversy that now surrounds the U.S. practice of interning American citizens of Japanese heritage and the divided perspective it engendered.

The Japanese Americans who joined the Seabrook workforce in 1944 (as well as the 150 German prisoners of war housed in nearby Parvin State Park who labored there at the time and future European workers hired after the war) became part of a culturally diverse group of employees whose customs and practices were retained and honored by the families who settled there. It was exemplary of the concept of America-as-melting-pot, but the circumstances surrounding the workers fell far short of being the American Dream.

Labor issues had existed at the Seabrook industry during the early 1930s and employees had to battle for more than simply their wages. In a 2020 opinion piece for the nj.com website, John Seabrook, grandson of the company’s founder Charles F. Seabrook, offered a frank account of workers’ circumstances in the business’ early years: “Seabrook workers were at the forefront of struggles to win laborers’ fair wages, job benefits and security, as well as racial and gender equality for farmworkers. For years, Black workers were let go before White workers during layoffs. Women, though considered more dexterous on assembly lines than male counterparts, received lower pay.”

According to the book Child Workers in America, Seabrook Farms adult workers went on strike in 1934 in what turned out to be a futile attempt to increase their hourly wages of 15 to 18 cents to a more appropriate 25 cents. Those workers, John Seabrook explained, “formed one of the first farmworkers’ unions in the country and elected Jerry Brown, a Black member, as president. That same year the union organized the largest farmworker walkout in U.S. history. The company responded by hiring local Ku Klux Klan members to attack picket lines.”

Workers eventually received a higher salary, but it wasn’t until 1940 that minimum wage reached 30 cents an hour. According to online sources, the U.S. Labor Department increased the minimum wage to 40 cents an hour one year prior to the arrival of Japanese Americans at Seabrook Farms. It would be another 11 years before it would be raised to one dollar an hour.

Hiring Japanese Americans then interned in camps throughout the South and West involved a process that served as a sort of audition. According to a 1995 issue of Humanities, the publication of the National Endowment for the Humanities, Charles Seabrook “invited the three-person Relocation Commission of the Jerome Camp in Arkansas to visit Seabrook Farms,” where they could observe “apartments and bungalows for Seabrook employees—and a library, community center and dining hall. The Japanese Americans were offered lodging, lunch and utilities for six months; the government would provide the train fare from the camps. In return, the Japanese Americans would agree to work at Seabrook Farms for six months.”

The Relocation Commission liked what it saw and subsequently encouraged detainees to move to South Jersey.

Work, conducted in 12-to 15-hour days, consisted of picking and packaging beans and spinach, and, to its credit, Seabrook Farms offered a salary of 47 cents an hour, which Humanities notes was “then considered a good wage…”

But good pay and generous accommodations weren’t enough to prevent the dichotomy created from transferring interned families to the fields and factories of Seabrook. As John Seabrook commented in his opinion piece, “For some families, the company’s promise of jobs and housing represented a new start. For others, Seabrook was a place of economic exploitation and lost rights and freedoms.”

Next Week: After the War