Books All Their Own

What BookSmiles is all about—books to establish a home library.

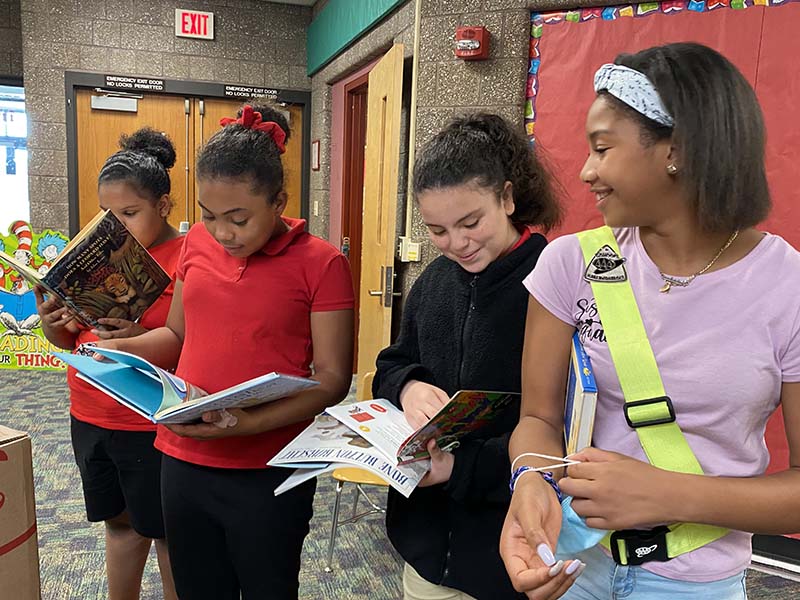

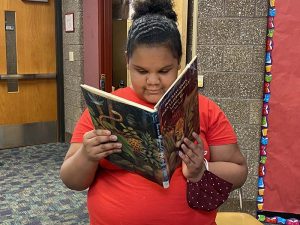

It was smiles all around when the books arrived at Dr. William Mennies Elementary School in Vineland. Several students came into the media center as volunteer Jane Arochas, a retired Vineland teacher, opened the boxes of new or like-new books that will be given away this week. Nine classroom libraries are out of commission due to a fire last month at the school.

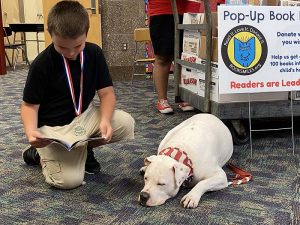

“That was really one of the main reasons I wanted to donate,” says Arochas. This is her fourth year hosting a pop-up book fair at Mennies. She rattles off the other schools she’s been to: Durand, Sabater, Wallace, and more. Jase Farside, a first grader, was happy to be able to take home a Scooby Doo book and paused to read it to Cole, Mennies’ famous deaf dog.

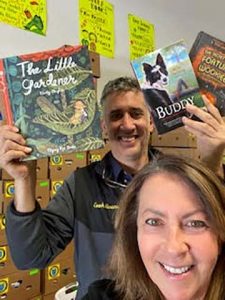

The books are courtesy of BookSmiles, an organization started by Larry Abrams, a Lindenwold teacher whose goal is for every child to have book-wealth. It is a term he made up; it means 50 books in a child’s home library.

“Even if they are living near poverty, I want them to have a reasonable library,” Abrams says. “We want them to become book donors themselves.”

It is an auspicious goal, but in the four years he has been at it while still working full-time he’s made tremendous progress. Over 500,000 books have been given away, and he now distributes 25,000 books monthly. More than 89,000 students in New Jersey and Philadelphia have received books. He has 46 active collection bins. Over the last four years, he’s had 2,500 people involved in collecting and distributing. There are 85 active volunteers, not including teachers.

Abrams’ passion to become the Robin Hood of children’s books was ignited by a student, a senior in his class who had a two-year-old. He asked her which books she was reading to her child and she laughed, explaining that not only could her child not read, they just didn’t do that. Having first taught in an affluent district where kids were prepared for high school English and then moving to Lindenwold, a less privileged district, Abrams saw stark contrasts.

“Access to books at home leads to academic success,” he contends. “They are less likely to drop out, less likely to go to jail.”

It is important to give access early; he argues that babies and toddlers need books in the house.

“It is a solvable problem, one book at a time,” he says.

Abrams now coordinates a network in which books are donated in wealthy districts and distributed in less affluent districts or “book deserts” to irrigate them.

“I started doing this out of my classroom, but I ran out of space,” Abrams recalls. “Then it was my garage, but I ran out of space. Townsend Press, a publisher in Berlin, was generous. They publish the Bluford Series books which are for reluctant readers. They saw merit in what we do.”

Townsend Press donated warehouse storage, but Abrams is again running out of space.

Arochas finds Abrams’ work terrific. She met him first at a literacy conference and then at a synagogue in Cherry Hill where they both were teaching several years ago. She started collecting and distributing for BookSmiles in our area.

“I saw the need for kids to have books at home that they could keep at home. They will read more,” Arochas, a literacy expert, explains. “Studies have shown that reading at home and having access to books leads to academic success. The kids love when they get a book and they can keep it. We tell them, ‘When you’re done with it, give it to a little brother or sister or someone else.’ ”

Abrams hopes his book fairs across the region have a positive impact against what is termed the summer slide.

“If they don’t have enrichment—if they’re not in a text-rich environment, from June to September—on average their reading drops half a grade,” he notes.

Putting books right into the hands of the students is the BookSmiles’ antidote.

Within the last three months, BookSmiles has given away 28,000 books through the Food Bank of South Jersey.

“The Food Bank of South Jersey has great logistical infrastructure,” says Abrams. “Our Special Sauce is to have teachers come to the Book Bank. They will drive up to 45 minutes to the Book Bank and leave with 100 books to give to their students. The books are free, but we ask for a $25 donation. They leave with $300 to $400 in books. Our stuff is new. We think it’s insulting to give underserved kids bad books. We think it’s beautiful for a teacher to give the books.”

BookSmiles has only one part-time paid employee, who helps to coordinate volunteers.

“We’re currently in the middle of a campaign to get a 16-foot box truck,” Abrams says.

With the box truck, he hopes to be able to up his totals to 75,000 a month. “Next year, we’ll raise money for a 4,000-square-foot location so we can have up to 20 volunteers. Then we’ll truly make a dent.”

He explains the network and how it grows: “I collect in book-rich towns: ‘People give me half of your garage and become the book person in your region.’ I have people pack their garages with books. When they have 6,000 or 7,000 books, I bring a box truck. It’s going to work. I see it in my mind. Right now Mullica Hill is a mega collector. I need more mega collectors. The center of the hub is the book bank.”

The collectors do not need to sort. “I need them to collect in earnest. Each collector has collected thousands of books. They need to be social. They need to go and collect from someone unable to drop off. They give books to children. One of my goals is to be able to feed Cumberland County.”

Before COVID, VHS teacher, Linsday Thies, worked with the students to coordinate a book drive. “The kids get community service hours,” says Arochas. “I want to continue that next year. We want to do more.”