Beware This Plant

The blossoms and berries of pokeweed, or inkberry, may be pretty, but all parts of the plant are poisonous if ingested.

Penny-wise colonial Pennsylvanians added pokeweed’s berry juice to cheap spirits in an effort to pass them off as expensive port wine. Later the supporters of candidate James K. Polk showed their allegiance by sporting a sprig of poke in their lapel, a campaign button of sorts (Klimas and Cunningham).

Native American Indians and early Americans used the berry juice for inks and dyes, thus one popular name—“inkberry.”

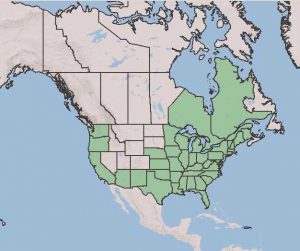

Pokeweed is native to southern New Jersey and across much of the continental United States as well as the eastern regions of Canada.

The plant is poisonous. However the young shoots are said to be edible, and in some rural southern states people eat them as a salad called “poke salad” (E. Hodgson). Some sources suggest various means of preparation to prevent toxicity, primarily involving boiling the leaves in water multiple times and discarding the liquid. As the plant matures the stem also becomes poisonous.

The Weed Science Society of America is more direct on the topic of toxicity: “All parts of the plant are toxic.” They discuss the boiling and changes of water, but ultimately they conclude,

“The ripe berries sometimes are cooked in pies. The use of any part of the plant as food, however, should be discouraged because improper cooking may not completely detoxify shoots and berries. Several berries may poison a child and 10 berries or more may sicken an adult. A child eating one berry is considered reason for concern. Deaths of children have been reported from massive consumption of ripe berries.” And one source suggested that even one berry could prove lethal to a child.

In case “discouraged” didn’t have the desired effect, know that pokeweed contains a “powerful gastrointestinal irritant, phytolaccine that causes effects ranging from a burning sensation in the alimentary tract to severe hemorrhagic gastritis (E. Hodgson).” In short, it feels lousy going down, induces cramping, and causes bloody diarrhea. Other reported effects include hypotension, dizziness, thirst, erratic heartbeat, vomiting, spasms, and even death.

A number of veterinary articles express concern regarding its harmfulness. Horses can be intoxicated by ingesting the plant. Fatalities have been reported due to respiratory failure and convulsions. On the other hand, veterinary research has used plant hemitoxin, toxins that destroy red blood cells or disrupt clotting, to make an immunotoxin that has been useful in treatment of bone cancer (S. Wynn, B. Fougére, Veterinary Herbal Medicine, 2007).

Pokeweed contains PAP, an antiviral protein that has been examined for its ability to control diseases in other plants. Where DNA of an unrelated organism could be artificially introduced, PAP was added to see if resistance to viruses might be the outcome. Treated tobacco and potato plants were in fact able to mount a strong defense to a potato virus (F. Cillo and P. Palukaitis).

Interestingly, the berries are used by the food industry for coloring. Now that’s a comforting thought (sarcasm intended).

The Cherokee people made a drink using grapes and inkberries, crushed, strained, and mixed with cornmeal. Jim Meuninck, author of Medicinal Plants, further relays that the plant’s leaves are rich in minerals and have more vitamin C than lemons. We will have to assume that the Cherokee knew the proper recipe. Meuninck also advises leaving the use of this plant to experts only. One of his students confessed to cathartic effects from eating leaves late in the season—a bad idea!

Birds do not suffer ill effects from eating this plant. They consume the fruit and pass the seeds on, essentially planting next year’s likely bumper crop. Thus, a circle of sustenance is created by the animals that enjoy it. I like to have some plants growing on the edge of the woods that surround my property, to attract wildlife. And I find the fruit attractive. But in garden areas that we frequent I try to pull it when it is young. Most people find it to be an aggressive nuisance.

As the plant matures the carrot-like tap roots are very hardy and really have to be dug out. When I have attempted to pull them and had the root remain in the ground, next year’s root sprouts and becomes massive, a trial for even the most adroit shoveler. So the sooner you remove it from an unwanted location the better.

When you brush past the plant and a berry is bruised, the juice will leave a purple stain on your clothing. Our dogs routinely run over them only to have visitors inquire if they have been injured, as the color can resemble a blood stain.

Folk medicine uses pokeweed as a purgative, poultice, and bronchodilator. Native Americans used it on joints for arthritis. Berry poultice was applied to sore breasts and berry tea was drunk for rheumatic conditions.

Today homeopathic doses are still used for many of the same conditions, as in a tincture for arthritis and chronic rheumatism. Pokeweed is also employed by some people as an intestinal cleanse, increasing consumption by a berry a day, which is a very risky business. It can also be used to induce vomiting.

As you likely know, many of our modern medications are poisonous if administered improperly or given in too large a quantity. Today’s cancer medicines can be deadly if not overseen with extreme care. Professional medical expertise is necessary when using dangerous medical toxins. This article in no way offers medical advice; it simply relays traditional lore and offers insight into modern practices.

I find the history of plants and their uses fascinating. Hopefully you have learned something different or new today about this powerful plant that is found in so many of our yards.

Sources:

Wildflowers of Eastern America, John E. Klimas and James A. Cunningham.

Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Wildflowers, Eastern Region, W. Niering and N. Olmstead.

Weed Science Society of America, online.

Peterson Field Guide, Eastern/Central, Medicinal Plants, Foster and Duke.

Falcon Guide, Medicinal Plants of N. America, J. Meuninck

Science Direct, journal summaries.

USDA, US Forest Service.