Precious Pinelands

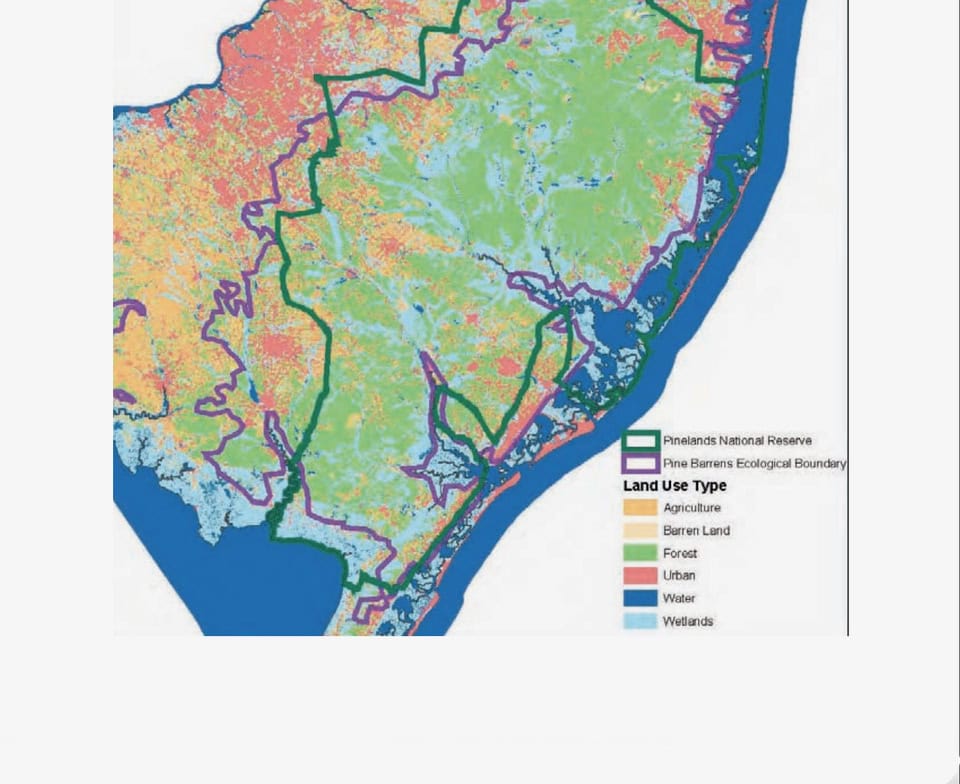

Green line shows the perimeter of the Pinelands National Reserve; purple line delineates the Pine Barrens Ecological Boundary. Courtesy Pinelands Preservation Alliance, Teachers Guide

PART 1 of 2: How a region’s natural and cultural resources were protected with the help of many advocates.

By Leslie M. Ficcaglia, CU Trustee Emeritus and former Pinelands Commissioner

The catalyst for the creation of the Pinelands Commission occurred in 1964, when the Pinelands Regional Planning Board proposed a “supersonic jetport” in Ocean County to reduce flight traffic over the New York metro area. The proposal involved a satellite city of about 250,000 people covering about 50 square miles in areas of the Pine Barrens that were environmentally sensitive, hosting large numbers of threatened and endangered flora and fauna. Considerable opposition ensued, uniting conservation efforts among such disparate groups as statesmen, farmers, hunters, and environmentalists. An enormous influence on the future of the Pinelands was Pulitzer Prize winner John McPhee’s book, The Pine Barrens, published in 1968. In it McPhee discussed the people, culture, history, and environmental importance of the area; however, in summary he predicted that the Pines were headed for extinction because of the monumental efforts it would take to preserve them.

Brendan Byrne, who became governor of New Jersey in 1974, was a friend of McPhee. He was impressed and moved by McPhee’s book and decided to make sure his prediction did not become a reality. In 1979, with the help of environmentalists, activists, scientists, citizens, and policy makers, he was able to pass the Pinelands Protection Act, safeguarding this special area from the threat of a jetport and ensuring that the 17 trillion gallons of potable water in the aquifer beneath the Pines would remain unpolluted.

To protect the Pine Barrens from urban sprawl and environmental degradation, the U.S. Department of the Interior worked with New Jersey officials both at the state and national levels to develop a management plan for this region of vast forests and small towns and cities. The National Parks and Recreation Act was scheduled as an omnibus bill that included legislation for the Pinelands National Reserve; it passed the U.S. Senate on October 24, 1977 and the House of Representatives on July 12, 1978. President Carter signed it into law on November 10 of that same year. The Pinelands National Reserve, occupying 1,100,00 acres in seven New Jersey counties and 56 New Jersey municipalities, was described as “the largest tract of wild land along the Middle Atlantic seaboard,” and became the nation’s first National Reserve.

Otters at play on a Pinelands stream. Photo: Leslie M. Ficcaglia

In contrast, the New Jersey state Pinelands Protection Area included a region of unbroken forest which covered only 39 percent of the National Reserve. The remaining land, making up the Preservation Area, consisted of towns and farmlands—in other words, less pristine locations. The state Pinelands Area also omitted land east of the Garden State Parkway and near the Delaware Bay. In 1983 UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) named the Pinelands a biosphere reserve.

Because of the amount of territory included and because of political and public pressures, the boundaries of the Pinelands National Reserve are not strictly based on environmental sensitivity. Adjacent lands sometimes have similar critical habitats. The Manumuskin River, one of the four waterways that were later included in the Wild and Scenic River protection program, is not protected. For some of its length the Pinelands line includes both banks but downriver it stops at its eastern edge, despite its being one of only two pristine rivers in the Pinelands National Reserve (the other one being McDonald’s Branch, which runs through Lebanon State Forest in Burlington County). Its status is due to the lack of development in its headwaters, which preserves its water quality, as well as the fact that the river is home to one of only seven known stands of the globally endangered sensitive joint vetch, or Aeschynomene virginica.

The Nature Conservancy (TNC)’s Manumuskin Preserve is an example of environmentally sensitive property in the pine barrens that is not within the political boundaries of the Pinelands Preserve. Although the parcel is not eligible for the state and federal protections afforded by statute, it is safeguarded by the conservation organization. Photo: Leslie M. Ficcaglia

The Pinelands Commission was established in order to protect the Pine Barrens and direct inevitable development to appropriate areas. It is governed by a panel of 15 people—seven appointed, one by each of the seven New Jersey counties within the Pinelands borders, seven appointed by the Governor, and one appointed by the U.S. Department of the Interior, making it a state/federal partnership.

So what is the Pine Barrens, and why is it so special? Partially because of its location in the center of the state and partially because of a fortunate juxtaposition of various soils, climates, and flora and fauna, it has become the safe harbor for many of New Jersey’s threatened and endangered species. From the State of New Jersey Pinelands Commission website: “The low, dense forests of pine and oak, ribbons of cedar and hardwood swamps bordering drainage courses, pitch pine lowlands, and bogs and marshes combine to produce an expansive vegetative mosaic unsurpassed in the Northeast. The Pinelands also contains over 12,000 acres of ‘pygmy forest,’ a unique stand of dwarf, but mature, pine and oak less than 11 feet tall.” It features 850 species of plants, including rare flora such as the curly grass fern and broom crowberry.

Pine Barrens woodland in early autumn finery. Photo: Leslie M. Ficcaglia

In addition, the Pinelands is characterized by unusual range overlaps where species of southern flora and fauna meet northern species at the edges of their specific geographical limits. For example the area is home to both the scarlet tanager, an eastern species, and the summer tanager, a southern species, and is the only place where they can both be found. A number of rare carnivorous plants are native to this area, including the pitcher plant, sundews, and bladderworts, as well as plants that receive their nutrition in the more usual way, such as the magnificent bright blue Pine Barren gentian and the purple Virginia meadowbeauty. In terms of animals, the bald eagle, the red-shouldered hawk, the barred owl, the black-crowned night heron, the northern pine snake, the Pine Barrens tree frog, and the frosted elfin (a butterfly) are some of the state endangered or threatened species. Although not technically at risk, the beaver and the river otter are somewhat reclusive and can be found here as well.

Sources:

State of New Jersey Pinelands Commission website: (nj.gov/pinelands/index.shtml)

Pinelands Preservation Alliance website: (pinelandsalliance.org)

Pinelands National Reserve (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinelands_National_Reserve)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Leslie Ficcaglia was the founding chair for the board of Millville’s Riverfront Renaissance Center for the Arts. She retired from her profession as a psychologist in 2000. But it is for her environmental activism that she is listed in Who’s Who in America. Her ecotourism brochure was distributed by Maurice River Township and became the impetus for her first website about the Wild and Scenic Maurice River. She worked on the task force to obtain federal Wild and Scenic status for the Maurice River and its tributaries.

Leslie served as a member of the Maurice River Township Planning Board for almost 20 years and as its chair for seven years; she was vice-chair of the Cumberland County Planning Board until 2007.

For 18 years, Leslie was the Pinelands Commissioner for Cumberland County, serving for a number of years as chair of its Personnel and Budget committee. She is a past trustee for the Association of New Jersey Environmental Commissions. She also served on the county Tourism Council, has chaired the Maurice River Township Environmental Committee, acted as trustee for Citizens United to Protect the Maurice River; and was a member of the Delaware Bayshores Advisory Council of The Nature Conservancy.

Leslie received the 2003 federal Environmental Protection Agency’s Region 2 Environmental Quality Award for Individuals for contributing to the protection of natural resources in the Southern New Jersey Delaware Bayshore Region and Pinelands Preserve.

Having lived on the Manumuskin River for many years on a farm that she and her late husband Anthony tended, Ficcaglia currently resides in southwestern France in the foothills of the Pyrenees.

Belted kingfisher on a Nature Conservancy preserve in the Pinelands. Photo: Leslie M. Ficcaglia