Women Filmmakers

In the early 1900s, it was not unusual to have women working in the silent-filmmaking industry—as directors, writers, producers, editors and camera operators. It’s time to bring their names to light.

The names Dorothy Arzner, Florence Lois Weber and Alice Guy-Blache are not easily recognized today, yet each has made her mark in film history by becoming the first woman to direct a sound film and join the Director’s Guild of America (DGA) or being credited with pioneering the technique of the split screen or earning the acknowledgement of the first woman to direct a film. The fact that one of them settled in New Jersey, 3,000 miles from the movie mecca of Hollywood, makes it all the more intriguing.

Two years ago, Margaret Talbot observed in a New Yorker article, “One of the stranger things about the history of moviemaking is that women have been there all along, periodically exercising real power behind the camera, yet their names and contributions keep disappearing…In the early years of the twentieth century, women worked in virtually every aspect of silent-film-making, as directors, writers, producers, editors and even camera operators.”

Talbot explains, “Some scholars estimate that half of all film scenarios in the silent era were written by women, and contemporaries made the case…that women were especially suited to motion-picture storytelling. In a 1925 essay, a screenwriter named Marion Fairfax argued that since women predominated in movie audiences…female screenwriters enjoyed an advantage over their male counterparts.”

Typing screenplays was how future DGA member Dorothy Arzner entered Hollywood filmmaking. Soon she was working behind the camera, her career spanning the silent era to the talkies and earning her the role of the first woman to direct a sound film.

According to online sources, between 1927 and 1943, Arzner helmed 20 feature films during a period when she was the only working female director in Hollywood. Some actresses whose careers she is credited with launching, like Katherine Hepburn, Rosaland Russell and Lucille Ball, went on to become household names. Arzner didn’t. She and her work simply disappeared.

As Talbot notes, “It wasn’t until a wave of scholarship arrived in the nineteen-nineties…that women’s outsized role in the origins of moviemaking came into focus again.”

By August 2000, the television network Turner Classic Movies was running a month-long tribute, Women in Film, that included 37 movies by female filmmakers, 14 of which had been recently restored. “Before filmmaking was taken seriously, women were serious about making films,” one of its ads read.

Florence Lois Weber’s seriousness about making films extended to establishing and operating her own studio, Lois Weber Productions, making her the first American woman to do so. A number of Weber’s films are co-directed with her first husband, Phillips Smalley, but she is usually credited as the auteur. In 1913, she experimented with sound in film production and used the split-screen technique. And, like Arzner, her accomplishments faded after her death in 1939.

“Now,” Talbott informs, “we are in the midst of a new round of rediscoveries—this time of women’s behind-the camera roles well into the golden age of Hollywood. There’s a romance to ushering lost women back into the light…[but] only a small portion of the movies made in the silent era, when women were particularly active behind the camera, still exist…As the film historian David Pierce writes, the industry considered ‘new pictures always better than the old ones,’ which had very little commercial value…”

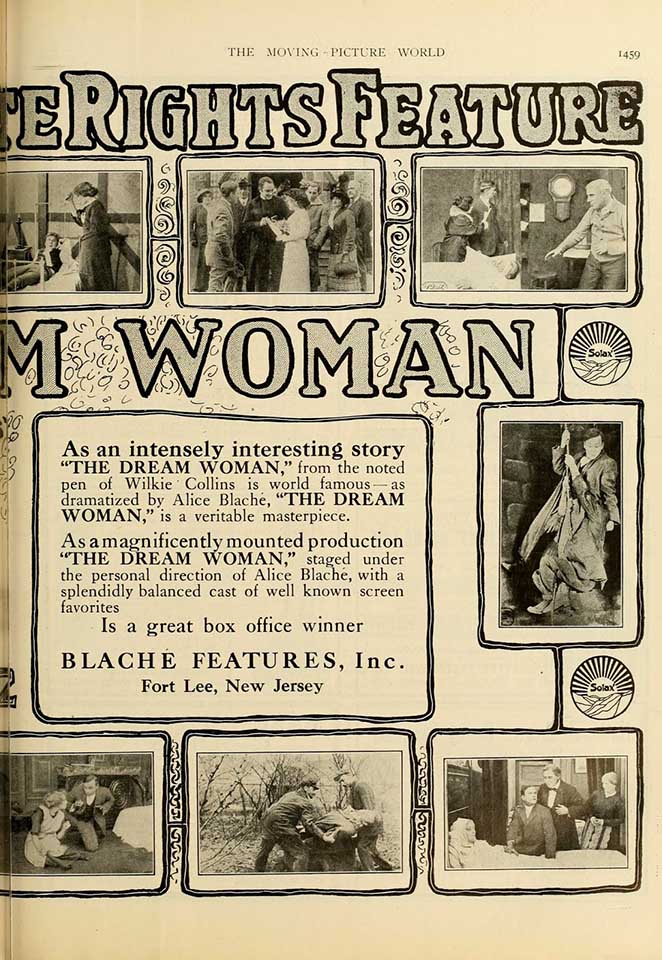

Three years ago, Kino Lorber released a six-disc Blu-ray set collecting some of the extant films from this period under the title Pioneers: First Women Filmmakers. It included 14 short films by Alice Guy-Blache, the first woman credited with directing a film.

Talbot notes that Guy-Blache was the “director behind some six hundred short films, including The Cabbage Fairy (1896), one of the first movies to tell a fictional story.” She was also the head of “a profitable production company” that eventually settled in Fort Lee, New Jersey. We’ll take a look at Guy-Blache’s accomplishments there when this series continues.