Salt Hay Farming

A recently cut section of salt hay at Cohansey Meadows Farm. Photos: J. Morton Galetto

Salt hay farming continues, with new and innovative approaches in tune with nature and climate change.

Salt hay farming is a traditional part of the Delaware Bayshore’s history. This historic land use transformed natural tidal marshes into diked impoundments in which farmers grew Spartina patens (salt hay). They used controlled flooding of the meadow for irrigation and introduction of salt. The natural salt marsh, with its mixed flora and Spartina alterniflora, was replaced by this commercial crop. The nutrients washed in by the tide that enriched the marsh soils and fed the fish nurseries were eliminated. The incremental increases in the marsh levels, brought about by the annual dying back of vegetation, were disrupted; the hydrology was altered.

Today much of the salt hay farms have been replaced through efforts at tidal restoration, implemented primarily by Public Service Enterprise Group’s (PSE&G) Estuary Enhancement Program. The company began its restoration efforts in 1994, returning more than 20,000 acres of what had become predominately phragmites-infested marsh back into Spartina alterniflora habitat. Phragmites is an exotic invasive plant that has little to no wildlife value; conversely, a mixed marsh with Spartina alterniflora supports many species and is necessary for the production of fish.

The company’s Estuary Enhancement Program was intended to offset the impacts on aquatic life from the intake structure at the Salem nuclear generating station located on the Delaware River in Lower Alloways Creek Township.

You may already know that the Delaware Bay is the second largest estuary on the east coast of the United States, with the largest being the Chesapeake Bay. Estuaries are crucial breeding areas for fish and shellfish. Many species have to leave the ocean’s saltier waters to produce their young; they need to come to a place where fresh and saltwater mix, an estuary—the Delaware Bay. Here juvenile fish have the lower levels of salinity that they need to thrive and also find shelter from larger fish and access to the nutrients that are washed over the marsh plain by the tide. It’s a nursery—with habitat, food, and shelter.

Now let’s fast-forward to the salt hay farms of 2025. PSE&G has removed the dikes and created a better environment for fish. A mixed marsh has been established, where a greater diversity of wildlife can prosper. There are also public use areas where people can appreciate the resource. PSE&G has tried to achieve the right mix of high and low marsh—a challenge, to be sure.

In the meantime, however, climate change has caused higher waters around the globe, which causes saltwater to encroach further inland. One of the results is the dying-off of upland plant species that do not tolerate salt. In past articles we have discussed climate-change impacts on trees at the fringes of the world’s coastal plains. At those locations dead trees stand as gray skeletons, reminders of forests that once existed—“ghost forests.”

The situation is further aggravated when pumped freshwater, used by residents, farms, and industry, is replaced by bay or seawater; this is called saltwater intrusion. People must dig deeper wells to access fresh water.

Prior to salt hay farming the marsh plain was built up gradually by layers of decaying matter. When salt hay was farmed, vegetation no longer accumulated because the product was harvested, shipped, and distributed for many uses.

Today, although the salt hay farms have been replaced by natural marshes whose detritus accumulates each season, this accretion is unable to keep up with rising sea waters. Ultimately we lose marsh, the upland is flooded, and upland vegetation that is intolerant of saltwater dies.

Innovative Salt Hay Farmer: The changing situation calls for new approaches, and, for some folks, new opportunities. Recently, CU Maurice members toured John Zander’s mixed-use property and salt hay farm.

Zander’s land is adjacent to former salt hay farms. He noted that on his land as saltwater encroached, there were areas on which different species of salt hay and salt-tolerant plants were still growing, as the salt-intolerant species died.

FAR LEFT: John Zander shows off a bag of salt hay

at his Cohansey Meadows experimental farm in Backneck, Fairton.

LEFT: Wyatt Bruck, 2025 Environmental Science graduate of Stockton University, did his senior internship at Cohansey Meadows Farm. He now works at the innovative farm. In foreground are bags of salt hay typically purchased by duck hunters and gardeners.

As a new kind of salt hay farmer, instead of diking meadows and controlling water flow over the ground Zander relies on new- and full-moon flood tides to distribute water over his fields. He cuts back phragmites and encourages places for salt-tolerant species of grass to grow.

In areas that were devoid of vegetation he has planted 30,000 plugs of salt hay. Now the higher flood tides provide the saltwater needed for it to thrive. In areas where phragmites is mowed he introduces big cord grass (another native salt-tolerant plant) that can out-compete the invasive varieties. He is testing his many innovations on some 1,600 acres of land, managing to sell over 2,000 bags of salt hay. His experimental approach apparently has promise.

Zander’s new-style operation, “Cohansey Meadows Farm,” lies along the Cohansey River in what locals call “Backneck”—Fairton, New Jersey. He named his family farm “Meadows” because historically meadow companies managed a marsh with a collective of users. They fished, trapped, and farmed, sharing a plot but exploiting different components. Zander is not new to exploring this marsh bounty; his father and grandfather augmented their income by trapping muskrats. His father was an engineer for Campbell’s Soup but he appreciated the bounty of the wetlands, and both he and his dad were involved in the muskrat trade.

Zander’s approach is far from traditional. He doesn’t bale hay with a baler, instead cutting it and stuffing it into bags. While a bale of salt hay sells for around $15 and has greater volume, a bag of his hay contains much less product but it retains its grassy appearance. It sells for $25 a bag and is excellent for camouflaging a duck hunter’s sneakbox (small hunting skiff). It lies more neatly in the garden than the baled product.

Much of Zander’s hay is sold to suppress weeds, thereby acting as a mulch. He uses no herbicides so that organic farmers can make use of his crop. People have purchased his hay to protect garlic, for goat food, and as finishing food for cattle, for duck hunters’ boats, for hamster bedding, and more.

Who’s involved? The Natural Resources Conservation Service sees the need to develop different approaches for combating sea level rise instead of simply watching forests die. Zander is one of the farmers who is proactive in developing a product that is tolerant to the habitat changes caused by climate change. The Conservation Service and other landowner incentive conservation grant programs are supporting his quest for solutions.

A stand of black walnut trees stand majestically on the salt hay farm. Owner John Zander spoke about the possibility of tapping the trees for syrup. The trees have scars that show evidence of being tapped in the past.

Among other efforts, Zander has removed acres of invasive autumn olive with a forestry mulcher. He continually explores creative ways to replace phragmites with more desirable native vegetation. He has planted persimmons, black walnuts, and elderberry.

Zander is also developing a market for selling plugs of salt grass to prevent erosion. In areas where salt is applied to winter roads, runoff often kills vegetation that is salt-intolerant. His salt grass can flourish in those environments. When seeded, salt grass is only about 15 percent to 25 percent successful, but his plugs have a 90 percent success rate. To harvest them he uses an undercutter bar and then further separates the slabs into plugs.

Zander is an example of the way people for centuries have looked to the marsh for bounty. He intends to work with the marsh as it has evolved and is changing, keeping ahead of the wetlands by reacting to the newly developed conditions. He strives to use a holistic approach that is in tune with nature. The challenges are many and his enthusiasm is contagious. I wish him success.

The Salt Hay Farming Tradition

In Colonial America farmers used dikes to prevent saltwater from advancing on grains and other crops. By diking marshes they accessed the highly productive soils of the marsh.

Salt hay farming was also used as early as the 1600s. Fibers of the plant were woven into rope. When concrete was curing salt hay was layered on top to keep the concrete warm. People also bought it for animal feed and bedding. In fact, cattle farmers often fed salt hay as a finishing meal to a herd before slaughter, because the meat tasted better. Today it is still used for mulch around plants to control weeds. At one point, a local casket mattress factory experimented with salt hay for stuffing, but it was a bit too buggy, according to well-known salt hay farmer George Campbell.

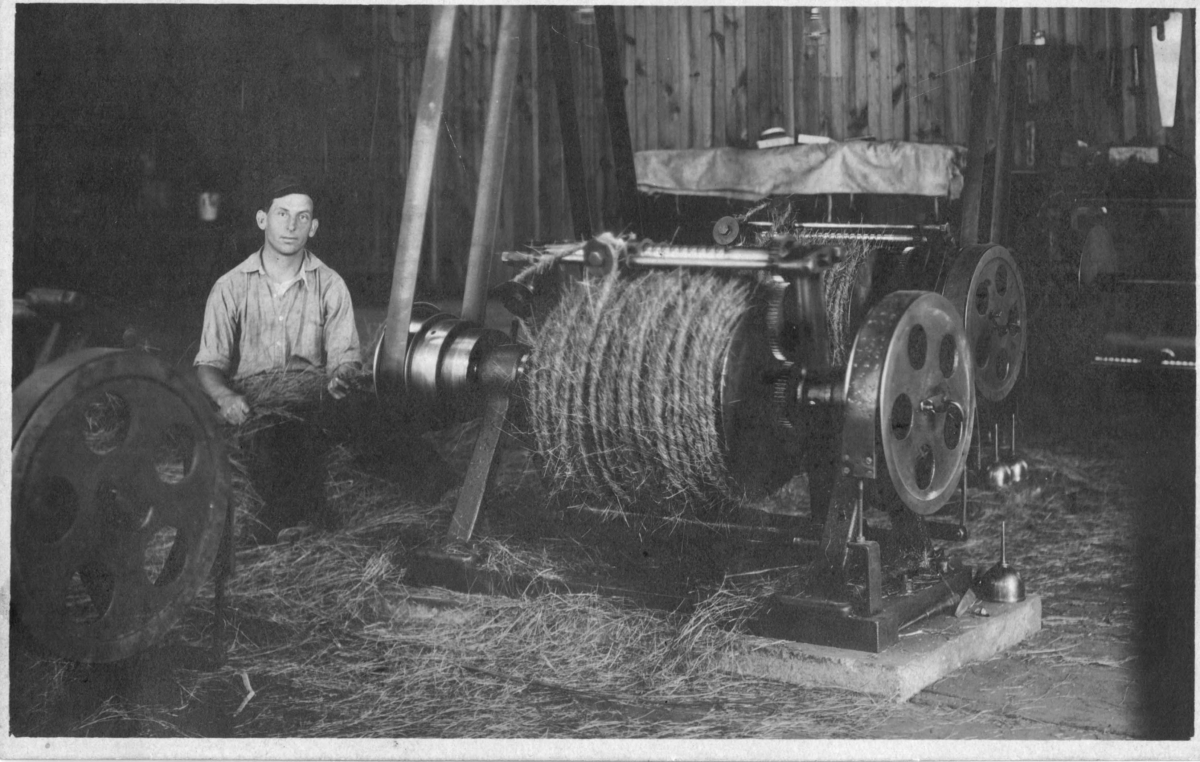

Port Norris Hay Rope Company, owned by O.J. Carney and A. Campbell. John Hollinger working the machine. Salt Hay Rope was used in making cast iron pipe. It was coated with clay and inserted in a larger mold. Molten iron was poured into the mold, and after cooling, the inner core of hay was burned out, leaving a hollow pipe. This machine is currently on display at the Bayshore Center in Bivalve, NJ. Photo courtesy of Jack Carney Family and Port Norris Historical Society

Until the 1950s, salt hay was loaded onto wagons via pitchfork. Photo: Gibson’s Private Collection, Port Norris Historical Society

To learn more about salt hay farming and rope making visit the Port Norris Historical Society’s webite: historicportnorris.org/salt-hay-farming.htm or historicportnorris.org/hay-rope-company.htm