Gouldtown: A Cumberland County Locale Rooted in Afro-Indian History, Genealogy

“One or another or all of them…were descendants of the Indian from the large Lenape settlement who married a Swede…and who had five children with her; one or another or all were descendants of the two mulatto brothers brought from the West Indies on a trading ship that sailed up the river from Greenwich to Bridgeton where they were indentured to the landowners who had paid their passage and who themselves later paid the passage of two Dutch sisters to come from Holland to become their wives; one or another or all were descendants of the granddaughter of John Fenwick, an English baronet’s son, a cavalry officer in Cromwell’s Commonwealth army and a member of the Society of Friends who died in New Jersey not that many years after New Cesarea…became New Jersey.”

“One or another or all of them…were descendants of the Indian from the large Lenape settlement who married a Swede…and who had five children with her; one or another or all were descendants of the two mulatto brothers brought from the West Indies on a trading ship that sailed up the river from Greenwich to Bridgeton where they were indentured to the landowners who had paid their passage and who themselves later paid the passage of two Dutch sisters to come from Holland to become their wives; one or another or all were descendants of the granddaughter of John Fenwick, an English baronet’s son, a cavalry officer in Cromwell’s Commonwealth army and a member of the Society of Friends who died in New Jersey not that many years after New Cesarea…became New Jersey.”

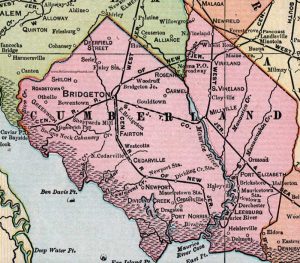

The above passage, from Philip Roth’s 2000 novel The Human Stain, is a brief and largely nameless sketch of the lineage on which Fairfield Township’s Gouldtown rests. Located in what was once a colony rests. Located in what was once a colony described as stretching north from Bridgeton to Salem and south and east to the waters of the Delaware on land purchased by Fenwick from John Lord Berkely in 1675, Gouldtown became a farming community formed by several principal families, including the Goulds, the Pierces and the Murrays.

The missing details from Roth’s account are provided by the nj.com website, which identifies that “the Murrays came here from Cape May and claim a Lenape Indian ancestry. Othniel Murray married a Swede named Katherine.” It also explains that “Anthony and Richard Pierce came here from the West Indies on a merchant ship and stayed. They paid the passage of two Dutch women who became their wives.” And the site informs us that the town was founded by Benjamin Gould, “the youngest of five children by Elizabeth Fenwick Adams, and a man of color named Gould. Elizabeth Adams was the granddaughter of John Fenwick…”

Ebony magazine wrote in its February 1952 issue, “The union [of Adams and Gould] caused a scandal which rocked the area for miles around and inflamed Fenwick with shame and rage.” It is reported that Fenwick, in his will, denied his granddaughter any inheritance of his estate. “Intermarriage between Negroes and whites in those days was rare,” Ebony noted, and “the couple were subjected to scorn and ridicule but remained together as man and wife and raised children who became the first of a long line of hardy farmers.”

“Gouldtown Traces History Back to First Intermarriage,” reads the headline of an article from an unidentified newspaper posted on wordpress.com, and it identifies Elizabeth’s husband as a coachman, but notes that his Christian name “cannot be found in the public records or ancient family histories of Gouldtown. He is the one Gould in the history of the area about whom very little is known. But there was one son, Benjamin Gould, who married a Finnish woman.”

We’re told by William Steward and Rev. Theophilus G. Steward in their 1913 book Gouldtown: A Very Remarkable Settlement of Ancient Date, Roth’s source for his novel’s history, that Benjamin, whose surname was alternately spelled Gould, Gold and Goold, was born between 1700 and 1705. While relatively nothing is known of his early life, his will “shows that he had accumulated considerable property, which is still in the hands of his descendants, who have added to it. The inventory of his personal property, consisting of cattle, sheep, oxen and the like, aggregated £148…which was quite a sum for those days.”

The Stewards’ book also explains that “Gouldtown is comprised in two sections—following the two family names of Gould and Pierce, which were always known by their separate names, Gouldtown and Piercetown, but both known comprehensively as Gouldtown.”

The wordpress.com article refers to the Gould and Pierce families as “the two main branches of the community” who “followed separate paths of development. The Goulds were stolid, conservative, and for nearly a century, teetotalers, while the Pierces were long noted for their gaiety, love of music, dancing and generous drinking.”

As Roth’s novel notes, children in Gouldtown were “catechized in the schoolhouse by the Presbyterians – where they also learned to spell and read…” Education was a priority and the Stewards’ book reveals that “Judge [Lucius] Elmer, a distinguished Supreme Court Jurist of New Jersey… and his son were accustomed, on Sunday afternoons to meet in a schoolhouse and catechize the children of Gouldtown, in the neighborhood, in the years following the Revolution.”

The Stewards also offer evidence of the achievements of the town’s education process, quoting from an unidentified local newspaper of the time: “There is no section of our County more highly honored than is Gouldtown, from which men have gone forth to become widely known and honored. Bishop Benjamin F. Lee was for some time…President of Wilberforce University at Wilberforce, Ohio, of which he is now a member of the Advisory Board.

Another is Theophilus G. Steward, who, for many years was chaplain of the United States Army and now…ably fills a professorship at Wilberforce University. Yet another is Theodore Gould, who is a member of the Philadelphia Conference of his church…”

The Human Stain contains a description of how a character “learned the maze of family history,” hearing it repeatedly “from great-aunts and great-uncles, from great great-aunts and -uncles, some of them people close to a hundred…” In their history of Gouldtown, the Stewards find it “remarkable, too, for the known longevity of its people, who do not begin to grow old, as is often said, until they come to three-score years, and a number of whom have reached the century mark, one of whom (Ebenezer Pierce Bishop) is still living, at this writing, who is one hundred and six years old, and one of whom (Mrs. Lydia Gould Sheppard) was buried in the year nineteen hundred and eleven, at the age of one hundred and two…” n

This series will continue next week in the the author’s “Jersey Reflections” column.