Coyote Lore—and Facts

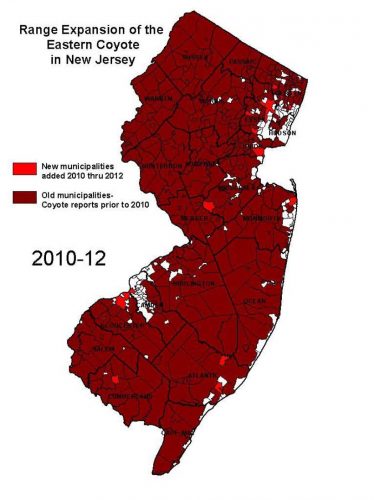

Eastern coyotes expanded their range in the 1980s and today are found throughout New Jersey, including urban areas.

I’ve been noodling on some Halloween themes for an October story. In past years we’ve covered the Jersey Devil, spiders, bats, and so forth, so I decided to read some werewolf lore to get some holiday mojo going.

Many sources suggest that the earliest references to “man-wolf” are in the epic Gilgamesh, written around 2100 BC in ancient Mesopotamia. The hero Gilgamesh rejects the romantic overtures of the goddess Ishtar, a risky decision since she has a reputation for changing men who anger her into wolves. The ancient Greeks also told many kinds of “man-wolf” stories, some of which possibly derived from tribal customs in which people donned wolf pelts for battle.

Native American shamans have worn wolf hides with the head draped over theirs in an effort to align themselves with the wolf’s power. Pawnee of the central plains identified with the wolf; the hand signal for wolf and for the tribe were identical, with the forefinger and middle finger in a “V”. Pawnee would sneak into enemy camps wearing the pelts; if dogs detected them the men would howl and the dogs would become quiet.

The lore of werewolves is widespread in European folklore and especially prevalent in the Ukraine. The tales vary but many follow a similar script, involving a curse being placed on a human, or a person having been bitten by a werewolf and thus acquiring the affliction of lycanthropy. This is a condition whereby the sufferer transforms into a werewolf on nights when the moon is full. In case you’re a cautious type, our next full moon is the beaver moon on November 8, Election Day; could that be an omen? Insert spooky music, please.

Well, if you were hoping I was going to suggest that we have werewolves in New Jersey you would be disappointed. In fact we don’t have wolves either. However, you will be interested to know that we have lots of coyotes, a subspecies that is larger than the western variety. There are 16 recognized subspecies in North America. Wildlife biologists using DNA analysis have shown that our eastern coyotes have hybridized with wolves, which is likely accountable for the larger size and color variations that we see here. Our coyotes range in size from 20 to 50 pounds, while western coyotes average 25 to 30 pounds.

I have never gotten a photograph of a New Jersey coyote; they are extremely wary with the exception of environments where they have become increasingly engaged with people. They also prefer the night hours (more spooky music, please). Human engagement primarily involves rummaging in garbage or outdoor offerings of pet food that can attract them. Feeding house cats or feral cats outside is an especially bad practice. People who have chickens, ducks, rabbits, and other farm animals are also at risk of attracting coyotes. Areas that draw rodents, like bird feeders or woodpiles, can also invite visitation from these larger mammals.

We began with a myth and our coyotes have a myth of their own. Many people believe that our state Fish and Wildlife department introduced coyotes to New Jersey. This is not true! It is possible but unlikely that private citizens may have imported them. Coyotes are an extremely adaptable mammal and they probably simply expanded their range. Wildlife biologists assert that since humans have tended to keep larger predators in check, coyotes have lost their primary enemies and have flourished. In fact, nearly every major city in the U.S. has coyote records, including New York. Years ago I read an article about scientists tracking them with radio collars in New York City, where folks actually came close to them but never knew!

We began with a myth and our coyotes have a myth of their own. Many people believe that our state Fish and Wildlife department introduced coyotes to New Jersey. This is not true! It is possible but unlikely that private citizens may have imported them. Coyotes are an extremely adaptable mammal and they probably simply expanded their range. Wildlife biologists assert that since humans have tended to keep larger predators in check, coyotes have lost their primary enemies and have flourished. In fact, nearly every major city in the U.S. has coyote records, including New York. Years ago I read an article about scientists tracking them with radio collars in New York City, where folks actually came close to them but never knew!

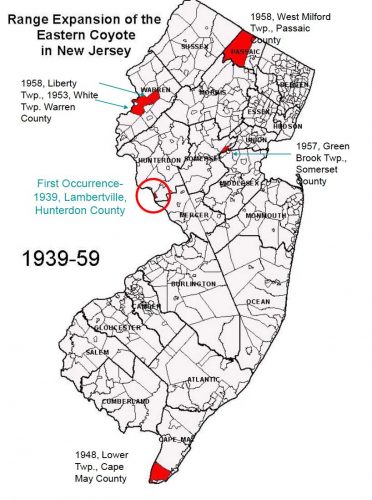

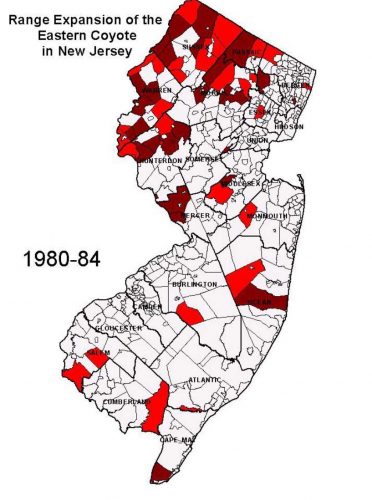

The first known occurrence of coyotes in New Jersey was in Hunterdon County in 1939. After this incident reports of seeing them were occasional, but in the late 1980s their numbers really increased. Today they are found in every county and nearly every municipality. The New Jersey Department of Fish and Wildlife has an excellent series of maps showing this range expansion for each decade since 1959. It splits the 1980s in half, showing the later part of that period with an astounding increase in their population.

Although I’ve never photographed a New Jersey coyote I have seen them a number of times, and I have observed their scat with great consistency. The first time I saw scat was at Higbee Wildlife Management Area, in Cape May in the 1980s. Many naturalists noticed it because it is very distinctive. It resembles dog droppings in shape but not in contents; it almost always contains fur and when it dries the texture looks a lot like spent charcoal. Using sightings and these types of signs, NJ Fish and Wildlife mapped the tip of the Cape May peninsula as being a frequented area.

Most often I have seen a coyote crossing a path or a road and even then I get just a glimpse, since most are very wary. They generally look like a scrawny German Shepherd in shape, and they tend to carry their tail characteristically downwards. In the east most are shades of grey with a black-tipped tail. Those I ‘ve observed in Wyoming have had a lot of blond on their chest and belly and are shorter and smaller—and in my unsolicited opinion are prettier than the eastern subspecies. In fact some that I have seen here, and those in pictures that local folks have taken, often look downright frightful, although I have noted some robust and healthy-looking specimens in Commercial and Downe townships.

While doing a bird survey some 20 years ago I was calling owls for people to tally. I heard a siren-like sound, and asked, “What was that?”

A few folks replied, “The Dividing Creek Co. siren.”

“Oh really?,” I asked skeptically.

I switched from whinnying and trilling like a screech owl to howling like a coyote. Within about 10 minutes, we could hear the calls of coyotes as they moved through the woods around us. “Really, the fire house?” I asked my companions. Everyone giggled. That is as close as I have come to a “man-wolf,” and as close as I wish to get. n

Sources for article:

New Jersey Fish and Wildlife

Pat O’Neal, Wolf Song of Alaska

Animal Diversity Website

Rutgers NJ Agricultural Experiment Station, Bulletin E367

Larson, Rachel, “Effects of Urbanization on Resource Use and Individual Specialization in Coyotes” PLOS ONE, vol. 15, no. 2, 2020