Holly Wood in the Pines

Daniel Fenton, Jr. shares memories of his “holly wood” childhood and his family’s pivotal role in Millville becoming known as “The Holly City of America.”

On the first day of spring CU held a number of tours at the newly acquired “Holly Farm” property. In a previous article we related that this 1,350-acre property had been preserved by a NJ Green Acres purchase finalized on January 9, 2020; the New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife will have management responsibility for the tract. It has been added to the Menantico Ponds Wildlife Management Area (WMA) and connects with the Peaslee WMA to the east. With this acquisition, there is now a secure corridor between two federally designated Wild and Scenic Rivers—the Menantico and Manumuskin. Spaces of this kind are critical to wildlife protection and movement.

Currently, the Division of Fish and Wildlife is working on creating new habitat where the orchard once stood and also on an adjacent field. Ultimately, the site will be the location of the Division’s South Jersey Regional office and it is anticipated to include interpretative features explaining habitat management for wildlife. Bluebird boxes on the site, placed by CU, have had significant success after just one season.

As noted in its name, the site was originally a holly orchard. During our tour we were fortunate to have Daniel Fenton, Jr. join us as a co-leader while we walked a portion of the property. A number of other Fenton family members accompanied us. Many locals in their 50s and older remember the “Holly Farm,” maintained by Dan’s father. Dan shared a condensed account of how his dad, and later he himself, became involved in holly propagation on the site. What follows are excerpts from his written account, with some details that he added in speaking with us on March 20, 2021.

We at CU thank Dan for sharing his memories with us as we continually strive to understand nature as well as our place within it. An unabridged copy of Dan’s story is available on our website.

—J. Morton Galetto, CU Maurice River

One day in December in the early 1930s, Clarence Wolf looked out his office window and saw a man driving a pickup truck loaded with beautiful holly boughs. He ran out to ask the man where he had found them. The man confessed that he’d gotten the holly on Mr. Wolf’s sandplant-owned land and didn’t mean any harm. He showed Mr. Wolf the location and Mr. Wolf sent out a crew to cut some boughs to send out to his customers. That Christmas present of holly boughs was a huge hit and Mr. Wolf got requests for additional boxes the following year. He liked gifting holly, being averse to liquor and cigars.

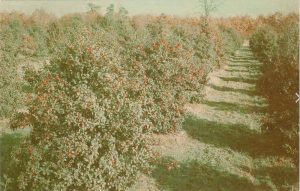

The whole concept of the holly orchard started in the spring of 1939 due to a late frost that killed the blossoms. Without blossoms, there is no fruit. While Mr. Wolf sent out boxes of berryless holly boughs and other evergreens that year, he vowed to make every effort to prevent that from happening again. Work began to plant an orchard, collecting specimens of the best-looking trees found growing wild.

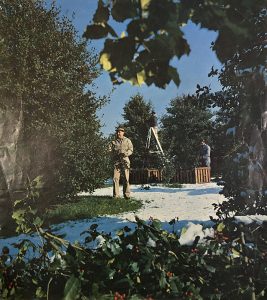

Mr. Wolf soon realized that he needed help to run the orchard and the NJ Silica Sand Company. That’s when he hired my father, Dan Fenton, a Millville High School Agriculture and Science teacher, who Mr. Wolf knew from his tenure on the Millville Board of Education. In 1949 Dad and a crew from the sand plant were tasked with further planting and maintenance of the orchard, which then occupied a 40-acre parcel of a 55-acre tract of land. They continued to seek out wild specimens. A two-story structure, ultimately called the “Holly House,” was built as a museum and welcome center. It was surrounded by hollies, and that is how it all began.

Mr. Wolf had seen “wind machines” in the Florida orange groves, used to prevent frost damage, and purchased three. These units had two diesel engines with two fixed airplane propellers, mounted on 40-foot rotating towers that mixed the warmer upper air with the colder ground air. Greenhouses were built to propagate the holly and produce new trees. In the summer my father and the crew would root cuttings of the most desirable cultivars. This method of using a vegetative cutting creates a clone; it is the only way to ensure that the genetic characteristics of the original tree or bush survive in the new plant. My father published two books on holly propagation techniques. As a result of his work he was able to select 14 distinct varieties, which were named after places in the area or in honor of noteworthy individuals.

Growing Up With Holly: I grew up on the Holly Farm and have many fond memories of Mr. and Mrs. Wolf and my dad. Mr. Wolf’s son, Franklin, lived next door to us and we played with his children, Margret Mary and Kay. John Wolf, Mr. Wolf’s youngest son, was like an uncle to us.

I remember going out to the orchard on weekends as a small boy to fight frost with the crew in the early hours before dawn. Oil-burning “salamander” heaters were placed throughout the orchard in April when the holly blossoms were forming, in order to warm up the air. Dawn is the coldest part of the day and it was an intense battle to keep the smudge pots or “salamanders” burning. The “perfect storm” was a clear night with a full moon, with no insulating layer to hold in the heat! At daybreak we would all gather together, drink hot chocolate, and walk through the orchard to assess the damage.

The “farm” was in fact an orchard and our “fruit” was the holly berry. Like any orchard operation, in the spring we needed to disc with a tractor and hoe around the trees to get rid of the weeds and the vines. My summer job was to keep the trunks clear. Fertilizer was applied to each tree by the handful. Grass seed (winter rye) was planted between the rows so they could be walked mud-free. Bee hives were placed around the orchard to ensure adequate pollination. We harvested a rich-tasting dark “holly honey.”

In the fall we constantly battled berry-eating birds. We had several carbide cannons and firecracker strings placed throughout the orchard. We would even walk the rows shouting and shooting 12-gauge shotguns loaded with blanks. The birds were undeterred. They also had a distinct varietal preference, stripping some trees and ignoring others.

Deck the Halls: In late November and December, dozens of bus tours would come to “The Holly City” to tour America’s largest Ilex opaca holly orchard and the “Holly House,” with a first floor that had been transformed into a museum. All the furniture in the Holly House was made from the white hardwood of the holly. The museum housed an extensive collection of fine china with holly motifs like Haviland, Limoges, and Wedgewood. Many visitors donated holly-related artifacts and the collection grew. The Holly Farm never charged for the tours. There was a small gift shop in the museum where holly-themed objects, small holly plants, and holly honey were sold.

Dad’s favorite artifact was a carving of the Lord’s Prayer made entirely from holly wood and said to be over 200 years old. My mother and my sister Kathy were always a big part of the whole “holly” enterprise. Mom ran the gift shop and remained an active lifelong participant in the Holly Society of America.

December was like Santa’s workshop, when once a year all the effort resulted in the annual holly harvest. We cut and boxed the holly in fancy red and white-striped waxed paper-lined boxes and sent the gift boxes all over the country.

A New Beginning: Mr. Wolf lost his daughter Alice and his son David many years ago. Clarence R. Wolf himself passed away on May 7, 1966, five days after his son, Franklin, died of a heart attack. Soon after his death, the NJ Silica Sand Company was acquired by Warner Concrete. Warner had no need for the Holly Farm and decided to sell the land and the orchard. Our father, along with a group of local businessmen, bought the Holly Farm and created a company called American Holly Products, Inc. We propagated various types of holly and sold containerized plants and cut holly boughs to garden centers.

Then disaster struck on February 10, 1983 when a heavy wet snow, lasting for two days, blanketed the farm with 18 inches of snow, crushing our quonset huts where the hollies were protected from the elements during the winter months and destroying all the saleable plants. That winter was the end of American Holly Products and the farm was sold to Atlantic Electric Company, which transformed the property into a conference center for a few years.

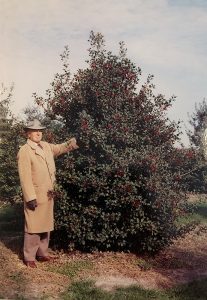

A Fitting Tribute: Many years later Dr. Elwin Orton of Rutgers University, having done many experiments in cross-pollination intraspecific hybridizing, developed an American holly with a noticeably darker, glossier leaf and a vibrant red berry. He named it Ilex opaca “Dan Fenton,” dedicated to our father. Dr. Orton also gifted us with a specimen that is growing in our yard today and is about 30 feet tall. Dad was deeply moved and honored by Dr. Orton’s unexpected gesture! Dad passed away in October a year later.

Sharing a Memory: I lived and worked on the farm for about a year during that period. I remember listening to the whip-or-will calls and hearing the mournful wail of a barn owl and the hooting of the great horned owls in the middle of the night. We were also treated to the spring peeper frog chorus and the sound of the occasional drumming of a ruffed grouse in the distance. I used to brew tea from the wild chamomile that grew in the sandy soil, right outside the back door to the HolIy House. I have many fond memories of the Holly Farm and our family is very grateful to know that the land will be stewarded in a manner that would have pleased the founders.