Tending Boys

Child labor was one ugly aspect of glass plants in Millville, anti-Semitism was another.

By the start of the 20th century, Whitall Tatum & Co., owner of two glass manufacturing plants in Millville, employed around 3,000 workers of all ages.

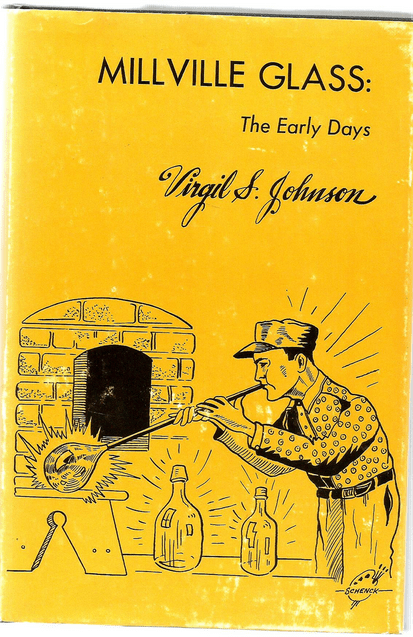

As in other glass factories and businesses, child labor was common at Whitall Tatum during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In his book Millville Glass: The Early Days, Virgil S. Johnson notes that tending boys, as they were called, “were sometimes mere ‘kids’ eight or nine years old, and while it was illegal to hire boys under twelve, it was done. When a state inspector would visit the plant, the kids were told to hide. Many times, it was said, the foreman would hide them under a barrel while the inspection was being made.”

The Child Labor Reform and the NCLC booklet identifies that the glass industry witnessed a move away from child labor significantly earlier than other manufacturers, but even with a decrease early in the 20th century the numbers are staggering. Official records show that the number of children under 16 employed by glass factories peaked in 1899 with a total of 7,116 before dropping to 6,435 by 1904 and 3,561 in 1909.

In his book, Johnson incorporates reminiscences of individuals who had worked at the company’s Glasstown and South Millville plants, including one resident who “used to tell of the influence Whitall Tatum Company had. It even extended into the schools.” According to Johnson, if the company “was short of boys,” it “would send word to [the] principal” of South Millville High School, who would “call out” a series of students and excuse them for the day to work at a plant.

Johnson also identifies advantages inherent to workers with sons, writing, “Adults who had four or five boys in their family were more likely to obtain work at a glass plant in those days than a man who had no boys.”

The tending boys were considered crucial to the operations of a glass factory, enough so that they managed to shut down the operations of two Baltimore plants in 1888 when they decided to strike over salary issues. According to a New York Times article that year, the strike closed “two of the largest glass manufacturers of Maryland and [threw] out of employment nearly 700 persons.”

Several years later, the tending boys at Whitall Tatum & Co. launched their own strike on September 20, 1891, jeopardizing far more workers. The New York Times reported, “nearly 3,000 employees at the flint and green glass works of Whitall Tatum & Co. are out of work as a result of the tending boys’ strike against the employment of fourteen Jews. This morning the firm closed the gates of the works and locked out every blower, presser, grinder, mold maker, lamp worker and laboring man.”

The Evart Review, a Michigan newspaper, claimed that the Millville tending boys were also looking for an increase in pay and called the lockout “the most complete ever known in this part of the State,” predicting that the loss to the company would “reach high figures” if the strike lingered. The article concluded by noting that “several Jewish families moved out of town today.”

A day later, the tending boys at the Cumberland Glass Works in Bridgeton also decided to strike. According to an article in The Roanoke Times of Virginia, the boys placed “iron bars across the gates…threatening to stone to death any Jews who attempted to go to work. Six Jews were discharged by the company, and the boys will now go to work without further trouble.”

Whitall Tatum’s response to its own strikers’ insistence on a pay increase and the firing of Jewish workers couldn’t be more different. “The firm refused to grant either demand,” the Evart Review reported.

The September 25, 1891 edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer reported, “The strike of tending boys at Whitall Tatum & Co’s flint and green glassworks is now at an end. It was a complete surrender on the part of the boys. A majority of them went back to work yesterday, and last night the leaders told the balance to go to work this morning. Today every boy is back in his place and all the factories are running to their fullest capacity.”

We’ll continue our look at Whitall Tatum when this series resumes.