Red-Headed Woodpecker

A flash of dark wings disappears and reappears, white patches accenting each wing beat. The stroboscopic effect captures my eye. When the wings tuck against the body the robin-sized bird navigates forward missile-like, undulating along on an invisible rollercoaster. On the glides, the red crown, forehead, nape, and throat become prominent. This is what happens when a red-headed woodpecker flaps and coasts past.

Many years ago artist Glenn Rudderow told me that colors are impacted by the shades they are painted next to; it’s all about contrasts and strokes. When it comes to contrasts our subject species, the red-headed woodpecker, has a fashion sense of red carpet magnitude, ooh là là.

When its wings are outstretched they and the body make a white T, surrounded by black. The secondaries (inner wing feathers) are white, as is the rump, upper tail-covers, and belly. The tail feathers, primaries, and coverts are black.

Let’s have a bit of anthropomorphic fun: Picture a person dressed in a white shirt, tail out, with white pants, black riding boots, a short-waisted black jacket, a red balaclava, and then paint his nose silver as a finishing touch. Voilà, ready for the masquerade party—one red-headed woodpecker. (You’re in luck; that is about the extent of my French vocabulary.)

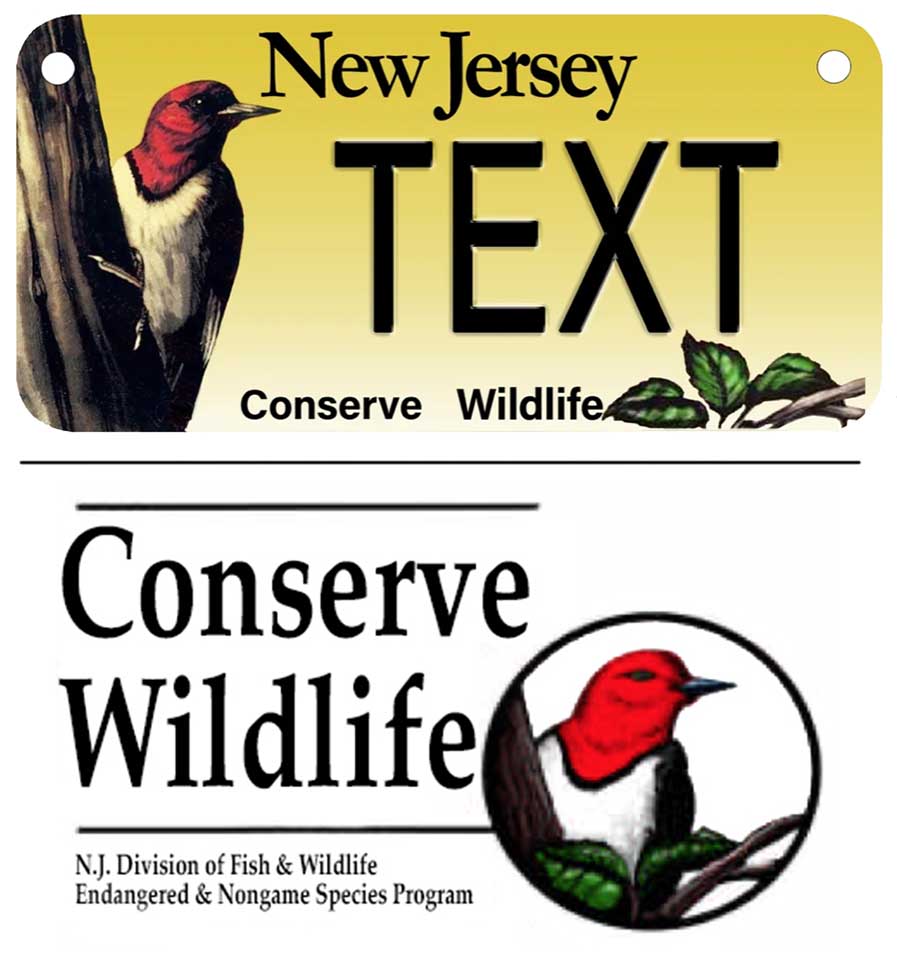

The males and females dress identically. Juveniles, on the other hand, lack the coloring but have the same patterning. These striking birds have historically been the poster child of the Endangered and Nongame Species check-off program and Conserve Wildlife, which encourage New Jerseyans to support the efforts to protect the state’s rare species and their habitats.

Sadly this dapper bird is on our list of rare species. It is classified as threatened in New Jersey and most of the northeastern United States. Its decline started in the late 1800s; it is one of the avian species that was impacted by the feather trade when plumes were in fashion for hats, especially true from 1909 to 1912. This period of “murderous millinery” threatened extinction of many creatures, especially those whose breeding plumage was in high demand.

The advent of the car has impacted the bird as well; vehicle collisions plague them. Further, like all cavity nesters it was affected by colonization and the industrial revolution, both of which greatly impacted its forest homes. Their numbers continue to decline in spite of restoration efforts.

The red-headed woodpecker has some other interesting habitat needs. It likes a mature forest with a low understory. In southern New Jersey our pineland forests with their oak/pine canopy and blueberry/huckleberry understory are favored. If the understory grows into a higher shrub-like environment the woodpeckers generally abandon it. A savanna-like environment of warm-weather grasses, sparse understory, and widely spaced trees is often attractive to them as well. They inhabit both upland and forested wetland. For nesting, trees must be mature enough to provide the required cavities. While widely distributed in the state they are few in number.

Because of their attraction to low understory, occasionally they are found in a shady cemetery that is free of sod but has more natural, grassy orchards, and even in suburban parks if there are widely spaced trees and snags for nesting.

The birds are omnivores, eating insects, reptiles, mammals, birds, and forest mast. Mast consists of seeds, fruit, acorns, chestnuts and the like. Lizards, eggs, rodents, and nestlings of other birds are on the menu. They can catch invertebrates on the wing and cache them tightly into bark crevices to be eaten later. They are known to defend their food reserves.

Outside of breeding season they are primarily nomadic seekers of forest mast, essentially travelling to find food resources.

Like other woodpeckers they are well-designed for navigating the trunks of trees with their zygodactyl feet; their long toes face two forward and two backward, and grip the bark with dexterity. Conversely, passerines normally have three forward and backward-facing toes, designed to wrap around branches. Waterfowl often have webbed toes for walking on muddy surfaces.

On my recent forest sightings these birds have remained mostly silent. Primarily they drum, squeak, rattle softly, or let out a squeak described as a “querr.” They are capable of carrying on but in most of my encounters they have been rather stealthy. Still, the red-headed woodpecker is uncommon and my encounters reflect that rarity.

On my recent forest sightings these birds have remained mostly silent. Primarily they drum, squeak, rattle softly, or let out a squeak described as a “querr.” They are capable of carrying on but in most of my encounters they have been rather stealthy. Still, the red-headed woodpecker is uncommon and my encounters reflect that rarity.

This is the time of year for courtship, when a male introduces a female to a number of nesting cavities and she seals the deal by picking her favorite. She will lay four or five eggs early in May to late June. Incubation is two weeks and paternal care lasts about a month. Adults split all parental duties from incubation to feeding. Occasionally a pair will have two broods in a season.

Some pairs will use a nesting site over the course of a number of years, presumably if the forest bounty is sufficient and the understory remains low.

Habitat loss is the species’ single greatest threat. Jane Fitzgerald of the American Bird Conservancy, coordinator of Central Hardwoods Joint Venture—an initiative to restore natural communities in open oak and pine-oak woodlands—described the bird’s dilemma and habitat needs well: “The red-headed woodpecker is the poster child of savanna-woodland systems. It’s critically important that the public support the kind of management—such as thinning and prescribed fire on ecologically appropriate sites—needed to restore healthy populations on both public and private lands.”

Sources

Endangered and Threatened Wildlife of New Jersey, B. Beans and L. Niles, entry Sherry Liguori.

American Bird Conservancy – Red-headed Woodpecker

* * *

Would You Like To Hear the Morning Chorus?

Sign up for a World Series of Birding Team guided walk on Saturday, May 21. Participants will stroll the many habitats of Hansey Creek Road (near Dividing Creek), listening to warblers at one of our area’s favorite hotspots for these neotropical migrants. The walk begins at 7 a.m.

• To sign-up: cumauriceriver.org – click on “Calendar of Events,” select May 21 and then the Green RSVP box. Free of charge. Or call the CU office at 856-300-5331.

What to bring: Insect repellent, visor, good walking shoes and binoculars.