One Man, Many Trees

Author traces her roots to a great-uncle who founded a national movement to save wetlands.

In 2018 I went on a trek to Minnesota along with my husband and my 89-year-old uncle Bob. It was an excursion that I had waited a lifetime to make. My uncle Robert “Bob” Morton was and still is sharp as a tack but the trip seemed to be a now-or-never decision. It was about roots—my roots.

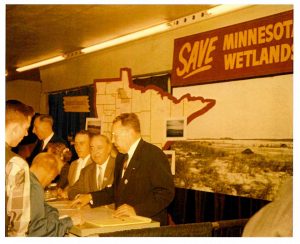

The story starts with my grandmother Mollie E., who throughout my childhood would mail us copies of The Conservation Volunteer, a publication by the Minnesota Department of Conservation (now the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, or DNR). She would send us wetland stamps and handwritten notes about one man’s efforts to restore a destroyed river valley. The man was her brother, my great-uncle Dick. By her estimation he was the greatest conservationist ever, and he was the founder of the “Save the Wetlands” program in the United States.

My grandmother was great at evoking hyperbole to tout the achievements of our family. My cousins who swam were all just on the cusp of becoming Olympians and I was a great scholar. The latter was proof that she was prone to exaggerate our greatness by many magnitudes. But I admit that her dramatic stories of her brother captured my interest. And conservation was one of the first multi-syllable words that I learned to spell. Had you been one of my childhood tutors, or even my current proofreader, you would understand this statement to have greater import than one might assume!

In later years I worked on a state task force to draft the current wetland laws for New Jersey. That prompted me to write to the Minnesota’s DNR for materials about my great-uncle Richard “Dick” Dorer. These materials recounted that he was not only the champion of wetland preservation in Minnesota but also the father of the “Save the Wetlands” program nationally. The more materials I perused about my great-uncle, the clearer it became that he was indeed a man of greatness.

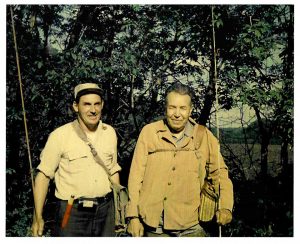

When my husband, uncle, and I arrived at the Richard J. Dorer Memorial Forest, Whitewater Valley Visitor Center, the DNR staff had arranged for a tour guide, Sara Holger, a woman whose role was one of educator. I remember her to be very personable. Her park ranger cap dwarfed her stature but in no way affected her enthusiasm. She took us to the Beaver Creek Cemetery where Uncle Dick was interred. There we read a lengthy description of some of his life’s accomplishments on a metal plaque that was affixed to his headstone and engraved with some highlights of his life.

After graduating high school in Bellaire, Ohio he went on to West Point. He was classmates with Dwight Eisenhower and was also a decorated war veteran, serving as a captain on the battlefields of France in WWI and earning a silver star, two French war crosses, the French military award Croix De Guerre, and a Purple Heart. He was said to be most proud of a citation for gallantry signed by General John J. Pershing.

For his conservation efforts he was awarded a Nash Conservation Award and the Valley Forge Foundation Medal.

The story I hope to relay is what I learned at the Valley Visitor Center about the Richard J. Dorer Memorial Hardwood Forest. In part it is the story of American settlement. At the Winona County Historical Society on the banks of the Mississippi River, not far from the forest, we received additional historical context about the destruction of America’s woodlands. The Valley was once a great lumbering area.

Why tell this story now? Well, we are nearing Arbor Day and in truth I’m feeling a bit nostalgic and a tad dramatic myself. Yes, it runs in the family.

My great-uncle joined the Minnesota Department of Conservation in 1938 at the ripe age of 48. He ultimately lived until 84 and my grandmother lived to 99. They were both active until the end of their lives. In fact my octogenarian uncle, a big man in stature, legendarily took a would-be convenience store robber to his knees by holding the wrist of his gun-wielding hand until the scoundrel relinquished his weapon. He simply said, “Son, I don’t think you want to do that.” Little did the young man know that this bear of a man was a decorated veteran who also planted thousands of trees to restore a forest. One can only imagine the crush of his huge labor-honed hands.

Like much of our nation the slopes of the Whitewater Valley were deforested for lumber, cordwood, and farming in the late 1800s. The invention of the tractor later allowed farming on steeper slopes to a greater extent than with horse and oxen. Then when crops were switched to corn from wheat, erosion intensified since corn doesn’t hold soil as well.

The steepest of slopes could not be farmed but they could be grazed. Cutting and burning of vegetated slopes opened up greater areas to pasture. The overgrazing of cleared hillsides killed the remaining vegetation. The deforested slopes could only absorb a three-inch rainfall in one hour without runoff. This compounded erosion problems, allowing more water and soil to be transported downhill.

By 1900 the Whitewater Valley experienced its first land-use-related flood. In 1938 Richard Dorer arrived on the scene at the Minnesota DNR. In that same year the town of Beaver had flooded 28 times. In fact we visited once-existing towns long since buried under many feet of soil. One church’s steeple was the only visible remnant of a vanished village.

Though many valley residents did nothing to cause the erosion and subsequent flooding, they were the most severely affected.

Uncle Dick lobbied for the use of land and water conservation funds to buy out these properties. It was during the Depression and most people were likely happy to have their destroyed properties purchased. Eventually he was key in orchestrating the expertise and will of many organizations to restore the Whitewater Valley. This was his job as a public servant, but it was also his passion and even in retirement he forged onward. Other agencies and groups involved in the task were the U.S. Soil Conservation Service, U.S. Agriculture Stabilization and Conservation Service, U.S. Civilian Conservation Corps, Whitewater Soil and Water Conservation District, Izaak Walton League, Winona County Fire Warden System, and the Works Progress Administration.

My uncle single-handedly planted thousands of trees and seeds as did many organizations. Some literature refers to him as a Johnny Appleseed. Streambank stabilization was key to the success of his efforts. Areas that remained in agriculture turned to contour plowing. The lower portion of the Valley is the Dorer Pools, comprised of wetlands for migrating ducks, water absorption, and flood minimization. Diversions, terraces, and ponds were built to reduce erosion and keep soil and water on upland slopes versus their rushing down into the valley. Forest management included replanting. Fencing was used to contain cattle and exclude them from woodlands and steep slopes.

No matter where conservation happens it takes a collective of people and a supportive government to make it work. And conservation has to happen again and again.

Today the Richard J. Dorer Memorial Hardwood Forest is an example of how proper land and forest management can create a sustained income, recreational opportunities, watershed protection, and wildlife habitat. The forest is a blend of more than one million acres of public and private lands, of which 45,000 acres are state-owned. The remainder is owned by private individuals and community groups. Much like the New Jersey Pinelands National Reserve,it is governed by a land use management plan and detailed ordinances.

I have seen in my brief lifetime how people neglect to look to history as a way to avoid repeating our mistakes. People thought that WWI would prevent WWII, and that WWII would always be a reminder that genocide and atrocities should never happen again. Yet humans continue on their harmful paths.

As a veteran my uncle drew parallels between the injustices to people and those to nature; he saw these as one and the same. He was an orator, a writer, and a poet. Next week, for Arbor Day I will feature his poem that was once read at Arbor Day celebrations around the country—“The Man Who Plants a Tree.”

For now, I leave you with his words: “It is my belief that a river belongs to no one. And it belongs to everyone. And no one has any right to contribute to the desecration of a river… at the expense of neighbors and fellow American citizens…”

It is with this philosophy that he led hundreds of people to restore the Whitewater Valley. Today I reflect not only on my uncle’s legacy but also on the importance of planting trees and on the many gifts they bestow.

Source

Minnesota’s Department of Natural Resources, publications

Whitewater State Park Visitor Center Minnesota

The Ghost Tree Speaks, by Richard J. Dorer