Kansas, 1918

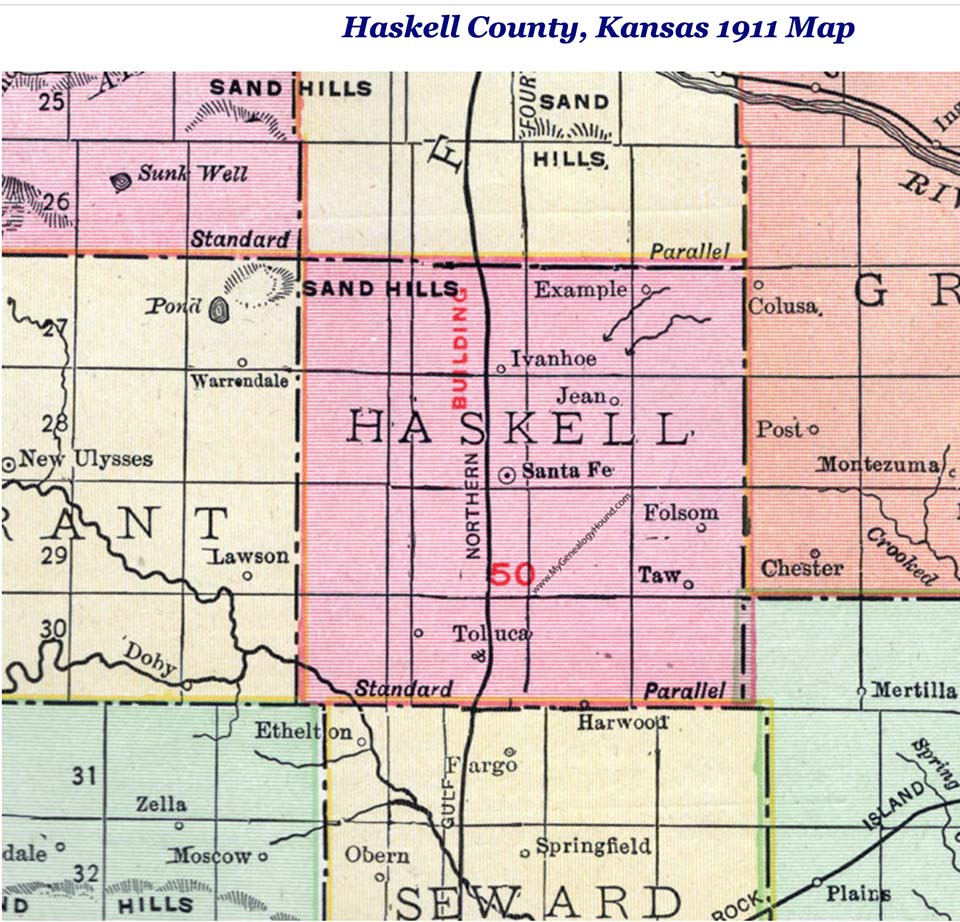

Haskell County, Kansas is where 1918 Spanish Flu likely originated.

The past pandemic year has been filled with speculation as to the source of Covid-19, prompting everything from conspiracy theories to assigning blame for its origins. Most global epidemics over the centuries experienced similar treatment, even if the finger-pointing lacks the accuracy and indisputable proof to certify that such conclusions are correct. But putting together the clues of such a complex origin might baffle even the best detectives.

Just over a century ago the Spanish Flu devastated the globe, claiming the lives of millions around the world throughout 1918. Its title, however, promotes the notion that the origin of the epidemic occurred in Spain. It didn’t. According to various online sources, countries fighting in World War I suppressed newspaper reports about the virus in order to maintain morale. Because Spain was neutral in the war, its toll of flu cases was reported internationally and the country became forever associated with the influenza pandemic, which was also referred to as the Purple Death because of the bluish tint it left on its victims.

In 2014, National Geographic laid the blame on the Chinese, its headlines stating that a historian was claiming the flu originated in China and that “Chinese laborers transported across Canada [are] thought to be [the] source.” They aren’t. According to John M. Barry on the National Center for Biotechnology Information website, “Influenza did surface in early 1918 in China, but the outbreaks were minor, did not spread, and contemporary Chinese scientists, trained by Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research… investigators, stated they believed these outbreaks were endemic disease unrelated to the pandemic.” Barry also identifies that the virus being spread by Chinese or Vietnamese laborers crossing the U.S. is merely speculation.

England was another culprit or, more accurately, its Army bases. What was diagnosed as a form of bronchitis among soldiers in 1916-1917 has been hypothesized more recently as the first documentation of the 1918 influenza epidemic. It isn’t. Barry reports that Journal of Infectious Disease editor Dr. Edwin Jordan “rejected it for several reasons. The disease had flared up, true, but had not spread rapidly or widely outside the affected bases; instead, it seemed to disappear.”

France and India were also suspects, but there is no evidence that the flu originated in either country.

So, for anyone wishing to point a finger at a guilty party, the United States has enough clues to arouse suspicion. Two years before the Covid-19 pandemic began, The Wichita Eagle reported that “one of the world’s deadliest influenza pandemics started quietly, inconspicuously…And it was here, in Kansas…The community was most likely Santa Fe, now a ghost town in Haskell County…” The newspaper described the Santa Fe location as part of the Kansas prairie “where dirt-poor farm families struggled to do daily chores—slopping pigs, feeding cattle, horses, and chickens, living in primitive, cramped, uninsulated quarters.”

Last September, Tom Levitt noted in The Guardian, “Wildlife, and our increasing proximity to wildlife, is the most common source [of pandemics], but farmed animals are not only original sources, they can be transmission sources or bridging hosts, carrying the infection from the wild to humans.”

In discussing 1918 Santa Fe, Kansas, The Wichita Eagle wrote, “It’s not known whether it started in the pigs or chickens or birds flying overhead. But it spread to young farmers…” by January 1918. Those farmers and others in Haskell County were treated by the local physician, Dr. Loring Miner, who recognized the threat of the strain and published his findings in Public Health Reports, a periodical of the U.S. Public Health Service, as a warning, despite its purported disappearance by late February.

Barry argues that “If the virus did not originate in Haskell, there is no good explanation for how it arrived there. There were no other known outbreaks anywhere in the United States from which someone could have carried the disease to Haskell, and no suggestions of influenza outbreaks in either newspapers or reflected in vital statistics anywhere else in the region.”

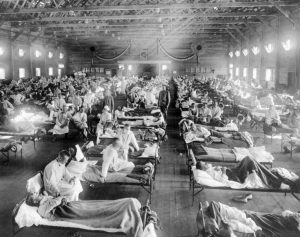

By March 4, a soldier stationed at Camp Funston, 300 miles east of Haskell, was reported as having contracted influenza. The Wichita Eagle identified the base as “the largest training facility in the Army, full of makeshift non-insulated barracks, housing 250 soldiers each. It teemed with soldiers from all over the Midwest, training for duty in France.”

“All Army personnel from the county reported to Funston for training,” Barry explains. “Friends and family visited them at Funston. Soldiers came home on leave, then returned to Funston.” The result was that within three weeks, 1,100 soldiers at the camp required hospitalization while thousands more appeared at infirmaries. Barry concludes that “the timing of the Funston explosion strongly suggests that the influenza outbreak there did come from Haskell.”

Rather than containing it, however, soldiers showing no symptoms were transferred to other Army bases in the U.S. and in Europe. By April, according to Barry, 24 of the 36 main military camps were overrun by the epidemic. In the same timeframe, “influenza was erupting in France, first at Brest, the single largest port of disembarkation for American troops.”

In the quest to understand the origins of the 1918 pandemic, a considerable amount of sleuthing over the past 100 years has gotten us to this explanation, which is still not an irrefutably proven fact. And, like the theories involving Spain, China, England, France and India, those regarding the U.S. have also had to contend with disinformation.

In 2006, a Worcester, Massachusetts newspaper, The Telegram, ran an article claiming, “Fort Devens [in Massachusetts] was the U.S. Ground Zero of the flu pandemic that spread around the world in 1918, killing more people than died in World War I. In early 1918, Fort Devens was one of the main centers of the U.S. war effort. On Sept. 1, its barracks were jammed with 45,000 soldiers waiting to be shipped to France. By the end of that month, Fort Devens was a charnel house filled with the dead and dying.”

This could be a fascinating historical revelation. But it isn’t.