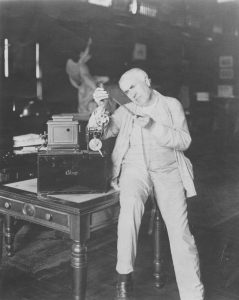

Edison and Film

Nearly two decades before the U.S. film industry staked a claim in Fort Lee, New Jersey, Thomas Edison had his West Orange laboratory employees searched for a way to combine image and sound in the nascent art form of motion pictures. According to the Library of Congress website, “Edison’s assistant, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, was given the task of inventing the device in June 1889, possibly because of his background as a photographer.”

Nearly two decades before the U.S. film industry staked a claim in Fort Lee, New Jersey, Thomas Edison had his West Orange laboratory employees searched for a way to combine image and sound in the nascent art form of motion pictures. According to the Library of Congress website, “Edison’s assistant, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, was given the task of inventing the device in June 1889, possibly because of his background as a photographer.”

James Monaco, in his book How to Read a Film, identifies Dickson as “an English assistant to Edison who did much of the development work, [and who] describes Edison’s first conception of the kinetograph as parallel in structure and conception with his successful phonograph: ‘Edison’s idea…was to combine the phonograph cylinder or record with a similar or larger drum on the same shaft, which drum was to be covered with pin-point microphotographs which of course must synchronize with the phonograph record.’”

Monaco notes that Dickson’s “first demonstration of his success to Edison on October 6, 1889 was a ‘talkie’…Edison had just returned from a trip abroad. Dickson ushered him into the projecting room and started the machine. [Dickson] appeared on the small screen, walked forward, raised his hat, smiled, and spoke directly to his audience: ‘Good morning, Mr. Edison, glad to see you back.’ ”

The concept of the talkie, we could say, had been introduced with that experiment, but it suffered from synchronization problems that halted its release to the public.

Edison’s new equipment consisted of the Kinetoscope, what The American Society of Cinematographers website identifies as a means “for films to be viewed by one individual at a time through a peephole viewer window at the top of the device,” and the Kinetograph, which Encyclopaedia Britannica describes as a camera that was “battery-driven and weighed more than 1,000 pounds.” Both the Kinetograph and the Kinetoscope were patented on August 24, 1891, the Library of Congress website reports.

By 1894, Edison began marketing Kinetoscopes. According to Britannica, “The Edison Company established its own Kinetograph studio (a single-room building called the “Black Maria” that rotated on tracks to follow the sun) in West Orange, New Jersey, to supply films for the Kinetoscopes that [the firm of] Raff and Gammon were installing in penny arcades, hotel lobbies, amusement parks, and other such semipublic places.”

The popularity of the Kinetoscope, however, had waned by 1895, and Edison was persuaded “to buy the rights to a state-of-the-art projector, developed by Thomas Armat of Washington, D.C… and in early 1896 Edison began to manufacture and market this machine as his own invention,” according to Britannica. Dubbed the Edison Vitascope, it “brought projection to the United States and established the format for American film exhibition for the next several years.”

A 1998 New York Times article reports that in 1901, “Edison opened a permanent studio on West 21st Street” in Manhattan and “aggressively defended his patents, form[ing] a consortium of film companies that agreed to use only his machinery. Those that couldn’t afford the patent fees were the first independents…Violent enforcement of the patents was not uncommon…”

Edison’s patent enforcement led some Fort Lee film studios in the early 20th century to maintain a lower profile than they preferred. The Barrymore Film Center website explains that Champion Film Company had its building “designed to look as little as possible like a movie studio so the Motion Picture Patents Company (dubbed “the Trust”, of which Thomas Edison was a key component) detectives would have a hard time finding it.”

In the New York Times’ assessment, “some of the responsibility for first leading the [film] industry out here, then driving it out, falls to the same man who created it in the first place: Edison.”