Denizens of Thompsons Beach

Our correspondent stood surrounded by 1,400 acres of tidal marsh, feeling like a marsh rat on an enormous stage.

On a balmy late fall afternoon I decided to take a trek to one of my favorite Bayshore spots, a place imbued with history: Thompson’s Beach. After parking I exited my car and took in the vast expanse of Spartina alterniflora grass that dominates the landscape. The cord grasses swayed as ripples of wind passed across their surfaces.

Most of the leaves had fallen except from the oaks, which were hanging onto their brown foliage just as long as they could; American beeches also retained a few. The shoreline was a haunting grey of leafless skeletons, with accents of green pines plus shrubs like bayberry. Snags killed by saltwater intrusion dotted the marsh plain. The Spartina, a combination of green and golden marsh grass, showed southern New Jersey at its finest. Saltwater-tolerant Baccharis halimifolia (commonly called groundsel bush/saltbush/salt marsh elder/sea myrtle) lined the Bayshore roads and paths.

What breeze there was had diminished in the late afternoon and the landscape was bathed in a warm honey orange. Older photographers like me think of it as a Kodachrome tonality versus the cool of Ektachrome. Nowadays there’s not even film in my camera, simply a card whose technology I have not a prayer of understanding. With it I can take endless pictures and spend hours deciding which two I will share out of the hundreds I shot. In an hour or two the sun would set and I’d resolved to witness the Bayshore’s best-of-show. But I was primarily there for another subject.

The shutting of my car door prompted a clapper rail to announce that this was his territory and I should take note. Maybe even scram. Two others answered with a descending series of clacks; well, I wasn’t alone. I stood surrounded by 1,400 acres of tidal marsh feeling like a marsh rat on an enormous stage.

It seems fitting to feel as such because so many operatic tragedies have taken place on this bayfront. I’ve played a bit part in a number of them. Two eagles looked over from dead snags, sizing me up. They had little idea of the role I had in their recovery, nor did they care. I reported many of their early nesting sites and advocated for their return, but unknowing, they were dismissive in their steely gaze. In the late 1980s there were a mere two, while today birders shrug and joke, “Oh, another eagle.” But many of us know that New Jersey Fish and Wildlife worked very hard to bring them back from the brink of extinction. I stared at one for a moment and pretended it winked knowingly. It did not.

I took a few moments to survey the empty osprey nesting platforms, taking note of whether repairs were in order. Osprey were vacationing in Brazil after a long season of raising young. There were a few natural nests to which I smiled and nodded; this was an encouraging sight. I thought of the hundreds of volunteers that CU Maurice River has coordinated since the mid-’80s, putting up more than 130 platforms. Fishing must be going well for them.

Pondering fishing I wondered, where is the troll of Thompson’s Beach Road? I offer that with an affectionate smile. It’s odd I hadn’t seen him on my last three trips to this storied spot. I envisioned him in his glasses, baseball cap with a cloth cape protecting his neck. Captain George didn’t wear one of those yuppie pre-made kerchiefs; no siree, just a cloth gave him UV protection. I thought I’d buy him one of those fancy toppers so we could laugh and I’d have an excuse to check up on him. A heron gull flew over and I suggested he just hang in there, and George would probably feed him later on. I wondered what name George had bestowed on him and I settled on “Harry.”

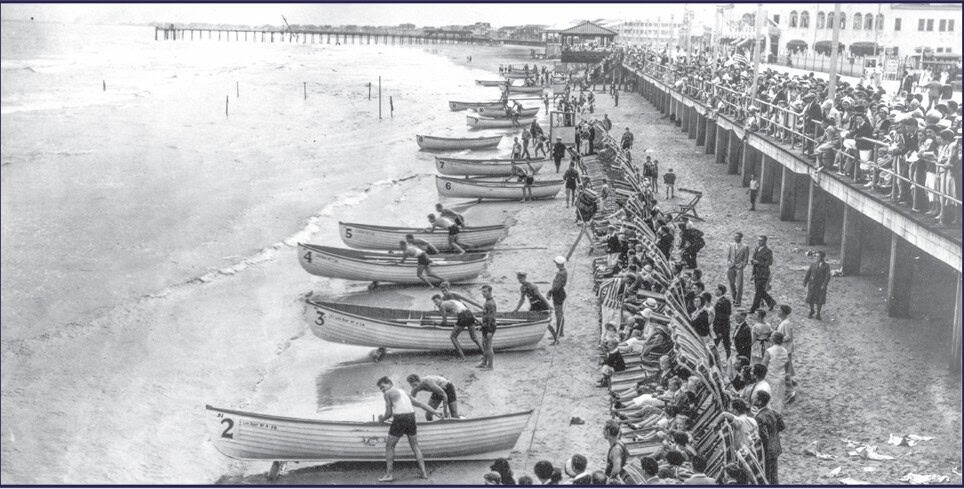

In the early 1800s this marsh was diked and farmed, and then in the 1990s PSEG purchased 20,000 acres of it; the section on the Maurice River Township site was 1,400 acres. Our New Jersey Bayshore was once dotted with homes, most of which were summer residences while some were permanent dwellings, and most were located on barrier islands just beyond vast marshes. Thompson’s Beach prior to the Great Appalachian Storm of 1950 had hundreds of structures, but after the tidal wave only 14 remained. That event predated me but Richard Weatherby, whose family was displaced by the storm, has shared their harrowing story. A tragic opera to be sure.

After years of the road being over-washed by extreme tides many of the remaining residents vacated. There were some holdouts and their stories ran in the newspapers, portrayed with high drama. Even the most hard-hearted of theatergoers took out their pocket hankies. In the end the last properties were condemned in 1997—the death of an era, in an on-going opera.

After the PSEG land purchases, CU Maurice River and New Jersey Fish and Wildlife advocated for public access to the Bayshore properties. PSEG was a willing and admirable neighbor in this regard, erecting boardwalks and viewing platforms at the sites. Currently construction equipment dots the parking area, in preparation of building a replacement viewing platform. And the township hopes to improve the existing gravel path with a grant to ensure that visitors can still make it out to the bayfront.

The path to the bayfront beckoned and I heeded its call. Who can resist picking up a water-tumbled brick from the shoreline and passing his fingers over edges smoothed by decades of wear and tear? I thought about how each one was once united in making someone’s foundation, fireplace, walkway, or whatever else. The standing hearth and bricks are props on this sandy stage. In May and June, shorebirds and horseshoe crabs will steal the show.

A few visits back I met naturalists Brian Johnson and Tony Klock along the path. They asked if I had seen the Nelson’s sparrows. “The what?” I queried in a display of ignorance, punctuating it further with, “I’ve been watching those birds and was unable to figure out what they were.”

“Yes, they aren’t endangered but they aren’t very commonly spotted; some folks call them orange sparrows.”

“Gosh, they are lovely.”

Since then I’ve returned several times to take photos and observe them, in varying degrees of human solitude. It is not uncommon for area residents to come to the Bayshore to catch a sunset or scan the marsh, but many times you have it all to yourself, much like the last residents of Thompson’s Beach. Captain George, I’m told, was one of the holdouts. He knows the marsh better than anyone. His daily meanderings take him up each traversable gut to check his gear for a catch.

I looked at the osprey platforms again and remembered when George guided us on October 28, 2012, a day before Hurricane Sandy, in putting up platforms. When we left, Thompson’s Beach Road was over-washed in water. Southeast winds, low-in tides, the moon, and sinking land were not in our favor. The following days would bring sadness to many on the Bayshore—yet another act in our coastal opera.

The light was changing fast; I had to stop reminiscing and focus on getting some pictures. A few fish jumped, startling me as they broke the silence. My eyes were getting attuned to the Nelson’s sparrows’ movements. The grasses made it difficult to take photos because the automatic lens focused on each blade of grass and not my subject. Eventually I got the hang of it, and I’d hung around long enough that they seemed to acclimate to my wispy whistles. I’d earned the trust of half a dozen or so willing to walk the runway for my photo shoot. Before I left the path I flushed a group of possibly 25. They were so much more abundant than I had realized.

When the lighting didn’t allow for any more bird photos I switched my attention to the sunset. The eagles took off for their evening roost, at this time of year most likely the nest on the Glades Road impoundments. By January they will all be setting eggs.

The clapper rails were really tuning up their orchestra, establishing their territories for the night. What seemed like three birds when I arrived turned out to be dozens, each calling with greater ardency than the previous. Then a few gave a half-hearted call as if to concede to the dominant birds.

The grasshopper sparrows fell silent, and the whistles of Nelson’s too. No longer could I see any northern harriers soaring, lazily surveying the marsh for rodents. A great horned owl let out a hoot. Soon a screech owl would surely whinny and trill. One act’s arias ended just as the pit tuned up for the evening performance.

I didn’t know what they were saying; I was simply dwarfed and humbled by their greatness.

Sources of interest:

Tidal Wave The Great Appalachian Storm of 1950 and Its Impact on New Jersey’s Bayshore Towns. D. Tomlin, S. Siejas and Ashley Hines.