A Tree, a Boy, a Fish

The tree and the boy stand witness to a forgotten Bayshore fishing industry.

Recently, a huge limb fell from a white oak on a wooded section in our yard. For hundreds of years, it was common for people to plant or designate a marker tree on or near a property line, and this is just such a tree. In fact, a survey marker is located alongside our mighty oak as it stands on a high bank overlooking the Maurice River. It is not tall and straight, but rather a gnarled behemoth that has doubtless lived through the ravages of time and wind, snow and rain, and likely the American Revolution, Civil War, and two World Wars. Often people speak of trees in an anthropomorphic fashion and tell of what they have “seen.” And I’m sure the oak has borne witness to many river and riverside events.

It evokes such thoughts, especially as it appears to be approaching its final days on earth. Or maybe I just read The Giving Tree too many times to my young daughters. They would always have to recite the last page by memory, since even in relaying this now my eyes are blurred a bit. The story is about a young boy who has a relationship with an apple tree, and the tree’s gifts that evolve as the boy matures until, eventually, they are both in life’s final stages.

I’ve been known to hug a tree or two and my great-uncle was a famous conservationist who wrote The Dead Tree Speaks, so I’m clearly fated to have a special affinity for trees. And you should be too, since trees give the gift of clean air and so much more. I will now step down from my soap box.

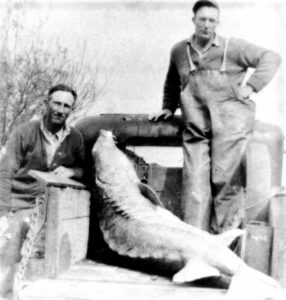

Catch at Old Ferry Reach

Catch at Old Ferry Reach

There is another “fish tale” about a catch at Old Ferry Reach. This one has become a real legend, and there are photos that document it. In the spring of 1946, Herbert Bradway and Leonard Pfeiffer caught one of the largest sturgeon ever pulled from the Maurice River. The 300-pound catch was six and a half feet long. The 43 pounds of roe brought in a high market price.

Back to the anthropomorphic story. There is a special denizen of the Maurice River area—a man who grew up on its banks, traveled its waters, and loves the river. He fished with his grandfather and tells the stories of the Maurice and its gifts. He experienced the shad and herring runs, fished for stripers, pulled nets, trapped muskrats, farmed its banks, lay in sneakboxes awaiting ducks, poled for rail birds, and witnessed families of otters. His clock and seasons were synchronized with the river’s. He crossed the Maurice’s ice on skates. He saw a Volkswagen driven from Fortescue to Miah Maull Lighthouse on an iced-over Delaware Bay. He knows the time-told names of the river’s reaches, an oral history, the lore passed from generation to generation.

Jennifer Lookabaugh Swift, who many readers will surely know—a woman who was indeed one of the reasons our river was designated by the National Park Service as a Wild and Scenic National treasure—attended school with this man, and she is his contemporary. Jennifer told me: “Richard Weatherby was simply known as the River Guy.”

When Rich was five years old, the Great Appalachian Storm of 1950 destroyed his family’s home on Thompsons Beach, so Rich’s family moved to a cabin on the property where his grandparents lived. The land was on the banks of the Maurice River and the entire parcel was leased from George Pettinos, Inc., with a 100-year agreement. The home’s foundation is all that remains, a familiar sight to many a hiker at the Nature Conservancy’s Bluff Preserve property.

My first meeting with Richard was when my husband was trimming trees on the banks of our newly acquired property on the river some 36 years ago. Rich came by in his aluminum pram and told Peter, “You oughten want to do that.” He went on to clarify in a few brief words, “Those roots are the only thing protecting your property from the next storm and there are some grand storms that I’ve seen.”

Being a woman who endeavors to keep her husband’s trimmers and saws in check, I valued Richard’s wisdom. And so began my love for Rich. As a bit of a sportswoman, a Field and Stream gal, I enjoy Richard’s ability to relay river stories along with a great respect for its bounty.

About a week ago, my husband Peter and I got to sit with Rich at a Wild Turkey Federation dinner. We told him the mighty oak had lost a lower limb, a limb as large as most trees, 60 feet long and a girth that one could hardly encircle with his arms. Richard knew the tree well. We all had a brief moment in which we pursed our lips and raised our eyebrows in a show of concern. We told him that at the fallen branch’s former connection with the trunk, it was partially hollowed out and a huge bees’ nest occupied that space; he said that the honey would be sweet and suggested some techniques we might use to harvest it.

About a week ago, my husband Peter and I got to sit with Rich at a Wild Turkey Federation dinner. We told him the mighty oak had lost a lower limb, a limb as large as most trees, 60 feet long and a girth that one could hardly encircle with his arms. Richard knew the tree well. We all had a brief moment in which we pursed our lips and raised our eyebrows in a show of concern. We told him that at the fallen branch’s former connection with the trunk, it was partially hollowed out and a huge bees’ nest occupied that space; he said that the honey would be sweet and suggested some techniques we might use to harvest it.

When Rich was 11, his brother-in-law gave him a whaling harpoon with a collapsible spearhead. Rich affixed a 30-foot nine-thread manila rope to it. He practiced throwing the harpoon in hopes of being successful in his quest for a gigantic sturgeon. A sturgeon got away from him at Owl Cove. And then, at 13, the opportunity presented itself again; all the aiming, tossing, and practice paid off this time. A massive sturgeon appeared in his net, beneath our mighty oak, the only witness to the event.

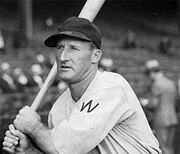

Goose Goslin at Bat

Goose Goslin at Bat

Leon Allen Goslin, was born in Salem and grew up to be a Major League baseball player. Better known as Goose Goslin, he was a left fielder known for his powerful left-handed swing and dependable clutch hitting. He played 18 seasons with the Washington Senators, St. Louis Browns, and Detroit Tigers, from 1921 until 1938.

According to Society for American Baseball Research, “Goose Goslin never truly earned the respect due a player of his caliber. He was generally acknowledged as a ‘money player,’ evidenced by his run of World Series appearances in 1924, 1925, 1933, 1934, and 1935. Goose referred to himself as a farmboy having fun playing the game he loved.”

After retiring from baseball, Goslin operated a boat rental company on the Delaware Bay for many years, until about 1969.

Richard raised his harpoon and successfully speared the great sturgeon near its dorsal fin. He lashed the rope over the oarlock and to the bow’s cleat. The massive fish towed his 14-foot wooden bateau, his net, and Richard on a “Nantucket sleighride,” the name given to the dragging of a whaleboat by a mammoth whale. It pulled him from the waters at the base of the oak all the way to Burchams’ swimming beach about 2,000 feet downriver—seven football fields!

Well, there was another witness: Goose Goslin was one reach upstream and couldn’t help but see that Rich had a big fish. Rich said everyone’s dream was to land a sturgeon. So Goslin pulled in his nets and came to Rich’s aid. Richard described the fish’s upper jaw and nares, or nostrils, as being like the snout of a pig and just like rubber. He said children used to cut that section of the nose off and use it just like a super ball.

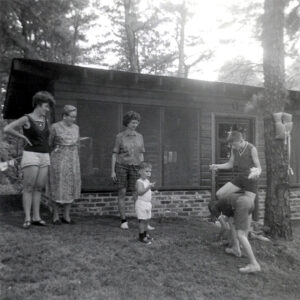

That day in 1958 at Burcham’s Point one of the twin sisters, Jeannette Burcham, took Richard’s picture with his prized catch.

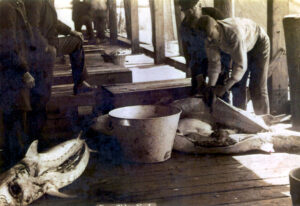

The Atlantic sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus) is a prehistoric-looking fish that was valued for its roe, or eggs, which were salted and sold for caviar. Locally, this was a lucrative fishery before its collapse. In fact in the mid-1800s to early 1900s, the harvest of sturgeon employed as many as 400 fisherman. It even out-competed Russian caviar.

The industry was centered at Bayside, formerly Caviar Point, on Stow Creek in Greenwich Township, Cumberland County. In the 1870s and 1880s, this port supplied more caviar than any place in the world. At its height in 1888, Delaware Bay fishermen caught six million pounds of sturgeon, while the rest of the East Coast fishery landed one million (Greenwich 2010 Environmental Inventory).

Sadly, overfishing and pollution decimated sturgeon numbers and the population collapsed in the early 1900s. Conservation measures were adopted too late. Sturgeon mature at 10 to 20 years of age in our region, and breed just once a year to once every five years. So sustaining a fishery means the difficult task of retaining breeding stock with a species that takes years to mature, further complicated by not producing young on an annual basis.

In 1890, more than 3,000 tons of sturgeon were harvested per year and 75 percent came from the Delaware Bay (attribution: Nat’l. Park Service and Lawrence J. Niles). Today, they are rare and the shortnose sturgeon (Acipenser brevirostrum)was listed in 1966 as nationally endangered, while the Atlantic sturgeon is considered threatened in most regions.

Richard’s catch proved to be about 400 pounds (minus tail and head). It provided 19 pounds of prized roe, which was salted pound per pound. Adults can live up to 100 years, grow up to 14 feet long, and weigh up to 800 pounds (Michele Byers). The purchaser paid for the cost of the salt plus $3.50 a pound for the roe and 60 cents for the flesh.

Richard said the only flesh he kept was the cheek that tastes just like beef filet. It is doubtful that sturgeon will ever make a comeback here, but many fisherman dream of just such an improbability. Occasionally, one washes ashore on the banks of Delaware Bay—a dinosaur of sorts.

If you allow me the liberty to further indulge myself in attributing human qualities to this tree, I hope to relay more exploits that it may have witnessed.

To read more about:

• Rich Weatherby check out CU Maurice River recollections at cumauriceriver.org/reaches/pg/recollections.cfm?sku=19

• and the family farm at cumauriceriver.org/reaches/pg/narratives.cfm?sku=12