A Book Launch

Newly released book causes our columnist to reflect on the launching of two bayshore initiatives and how each has grown and thrived.

Sometime between December of 1989 and March of ’90, CU Maurice River assembled a work crew to erect an osprey platform near the Mauricetown Causeway Bridge. Prior to the great infestation of phragmites this was likely our most viewed nest. (Today our members monitor 40-some).

Sometime between December of 1989 and March of ’90, CU Maurice River assembled a work crew to erect an osprey platform near the Mauricetown Causeway Bridge. Prior to the great infestation of phragmites this was likely our most viewed nest. (Today our members monitor 40-some).

I remember the day as chilly but warm enough to be muddy underfoot. Osprey platform installations had to be completed before the mid-March return of migrating osprey.

The entire time we were constructing the nest we could hear the steady drone of water pumps. Aboard the deck of what resembled a sunken or grounded ship, a small number of spectators curiously watched us from time to time. We went about our business of erecting the pole and when we completed the task at hand, we decided to see what they were about.

We inquired, “Hey, what are you folks up to?”

With levity intended, they replied, tit for tat, “What are you up to?”

We said we had just installed an osprey nesting platform. They thought our goal was optimistic; after all, New Jersey had once had 500 osprey pairs and was probably down to between 25 and 50 pairs, very scarce in those early days of recovery. Likewise, during the heyday of the oyster industry, 590 vessels called the ports of the Maurice River their home in 1903, but there were fewer than 20 in 2020.

We returned to our original inquiry, “What are YOU up to?”

They responded, “We’re restoring a 1928 oyster schooner; want to come aboard?”

We looked around at our work crew to see if folks were game and the head-nodding seemed to show interest, so we were soon on tour, with Meghan Wren and Greg Honachefsky as our guides. I knew that John Gandy had purchased a schooner with the intention of restoring it, but little else. He purchased it for a dollar, and by my estimation he paid $500,000 too much. This was clearly going to be expensive if it were ever to happen.

The previous owner, Donnie McDaniels, had bought it for the clamming license that accompanied the craft, recognizing the hull to have outlived its usefulness. But Gandy was enthralled by the old sailing schooners and had a vision of returning the it to its former glory and port. Today, I marvel at the visionaries who led the restoration process.

As we toured, there looked to be more water in the hull of that ship than in the river. We tried to be polite and hide our skepticism, but I think our smiles likely gave us away. They explained that this forgotten vessel had not always been a motorized craft but at one point in its glory days was an oyster schooner, traveling only with the wind. They planned to remove the pilothouse and restore the low-profile entrances to the galley and berths, equip it with masts, and sail it as a floating classroom.

Eddie DiPalma was with our crew and his father had been an oysterman for a number of years. He was familiar with shipbuilding and he shook his head in amazement at the task ahead of them.

Eddie DiPalma was with our crew and his father had been an oysterman for a number of years. He was familiar with shipbuilding and he shook his head in amazement at the task ahead of them.

We offered our best wishes: “Good luck.” And their reply seemed to have a trace of equal uncertainty, “Good luck with the birds.” Our mutual skepticism was justified.

Ultimately Wren and Gandy agreed that a non-profit, then called the Schooner Project, should be established to take the helm in the restoration process. In 1992 they received an Historic Restoration Grant and the boat was hauled out in 1994 for land-based construction. A professional crew augmented by highly skilled volunteers and greenhorns proceeded to restore the A.J. Meerwald. It was estimated that about 10 percent of the vessel was extant. After seven years of blood, sweat, and likely some tears, on September 12, 1995, the ship was christened with a bottle of champagne by Wren in front of a crowd of onlookers.

Recently, I had time to reflect on this day and the many years leading up to and following it, as I completed this recounting of the story. These were the days when the bivalve was king and Port Norris had more millionaires per square mile than any other town in New Jersey, all because of the oyster industry. Growing up I remember old timers saying that oystermen lit their cigarettes at taverns with 100-dollar bills and traded in cars when the ashtrays were full.

Back then, sails filled the Maurice River Cove and bayfront as they went in search of oysters. The Meerwald’s launch in 1995 was followed by 30-odd years of hard work while the Bayshore Center at Bivalve (BCB) restored the ship as well as the shipping sheds where they established a museum and ventured to keep people educated about the importance of this mollusk to our region, both yesterday and today.

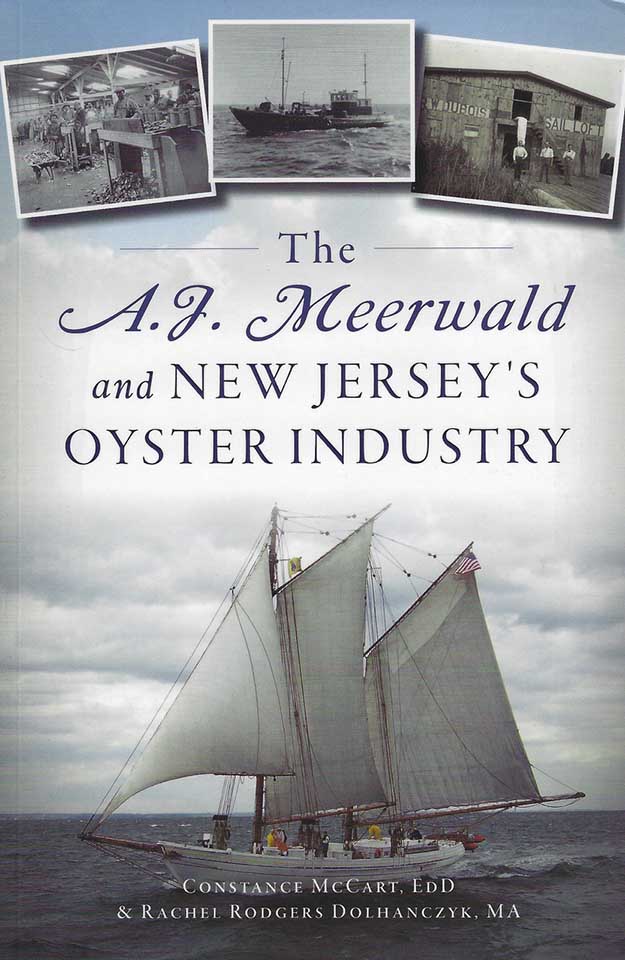

This history is part of our regional heritage, and in my humble opinion it is important to give generations an understanding of our past, present, and prospective future. BCB’s Museum Curator Rachael Rodgers Dolhanczayk, along with educator Constance L. McCart, have just written a book—The A. J. Meerwald and New Jersey’s Oyster Industry. It does a marvelous, detailed, yet succinct job of covering the history of the industry and restoration of the A.J., including important timelines for both. It is a must-read and a super gift.

During its six decades of history the boat had many uses and incarnations. Early days of the A.J. Meerwald, its service in WWII, and its return to oystering are described.

Captains often referred to their ships in human terms. “Well, wooden boats they creak and they groan, do all the same kinds of things as humans do. That’s one of the reasons they talk of the boat as being alive,” Captain Fenton Anderson told Rita Moonsamy in a 1983 interview.

The building of ships and prep work such as half models and floor sketches are discussed. The Delaware Bay oyster schooner’s shallow draft and wide beam are especially designed for our local waters and the task of harvesting oysters. Since these bivalves live in shallower depths, piling them onboard takes a wide craft.

People’s age-old love of oysters is also described in the volume. Oysters are especially nutritious and have been prepared in endless ways. In their heyday, beginning in the mid-19th century, menus would include such fare as oysters on the half shell, followed by oyster patties, turkey with oyster stuffing, Oysters Rockefeller, and broiled oysters and rolls. There were all manner of implements like silver oyster forks and fancy Haviland Limoges porcelain oyster plates with individual cells to accommodate each shucked oyster.

The book is also filled with interesting facts about the oyster and the industries surrounding it. Oysters filter up to 50 gallons of water each day, thus playing a critical role in the health of the bay. They are sessile; they do not dig or move like clams, but remain fixed and immobile. Their shells have been utilized for centuries as money, roadway material, utensils, decorations, a component in glass, chicken feed, and mulch. They were also prized by our predecessors, and half-buried oyster shell middens show us where Lenape encampments once stood.

Aspects of the industry’s oyster lease grounds, harvest methods, and the many ancillary enterprises that supported the oyster business are part of the text. Trains were used to deliver oysters to restaurants all over the east coast. The advent of canning led to the shucking of oysters and huge piles of shells. Thus sprang up the riverfront villages of Shellpile and Bivalve.

For many years oysters could only be taken under sail, but during and after the war motorized crafts were permitted. The evolution of the industry as each of these modifications took place changed the face of the business landscape and the health of the harvest.

Prior to spread of the disease MSX in the late 1950s, millions of bushels of oysters were harvested each year from 50,000 acres of oyster beds. By 1957 the disease had reduced the harvest to 10,000 bushels. In recent times the harvest has rebounded to around 100,000 bushels annually.

With shucking came the shuckers. The Afro-American contribution to the industry is both striking and poignant. The sharp, rhythmic sounds of many workers opening the shells to release the meat inside are described by those who worked there. From the ramshackle housing to the joys of a child growing up in this environment, it all comes to life in the words of people who lived along the waterfront—part of a heritage that is explored in this book.

My thoughts return to my first encounter with the A.J. In retrospect this was a memorable day. Two organizations, both now well-established in the community, were then in their non-profit infancy. The Schooner Project, known today as the Bayshore Center at Bivalve, and Citizens United to Protect the Maurice River, and its Tributaries, Inc. aka CU Maurice River met on that day. Each had their own lofty ideas of what they could accomplish. These two organizations continue to have many intersections in their missions, which shine a light on our natural and cultural history. We are using different tools but exploring the same region.

Today, osprey numbers exceed 650 pairs; of the oyster schooners only a handful are left. But because of the visionaries of the Bayshore Center at Bivalve, one magnificent vessel graces the Maurice River. In 1998 the NJ Legislature declared the AJ Meerwald New Jersey’s Official Tall Ship.

J. Morton Galetto served on the Board of the Bayshore Center at Bivalve for a decade or more. She was involved in many partnerships between the Center and CU Maurice River.