Your World, A Stage

These days, we’ve all become players in dramas, with our homes transformed into stages.

One of the victims of the current pandemic has been the string of venues housing the performing arts from concert halls to Broadway and regional/local theater. But theater seems to have simply transferred itself to real life.

Dramatic works written for the stage are largely confined to the setting of a room from which action and dialogue flow. The most conspicuous acknowledgement of this in the theater world is the title of Harold Pinter’s 1957 play The Room. But our current health crisis has, at least during the spring, given many of us the unique experience of becoming players in a dramatic work of our own making as facilitated by a mandated lockdown, our homes transformed into the stage equivalent of the “room.”

That may partially explain why I’ve been revisiting dramas on film and in print since the start of the pandemic, my choices also guided by what has transpired over this year. The movies have included Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen’s Enemy of the People, with Steve McQueen as the town doctor reviled and persecuted for his discovery of bacteria in the public baths that will jeopardize the town’s tourism and, as a result, its profits. Print selections consisted of a drama I saw 10 years ago on Broadway, David Mamet’s Race, which contains arguments that are only now being discussed in a national dialogue after George Floyd’s death.

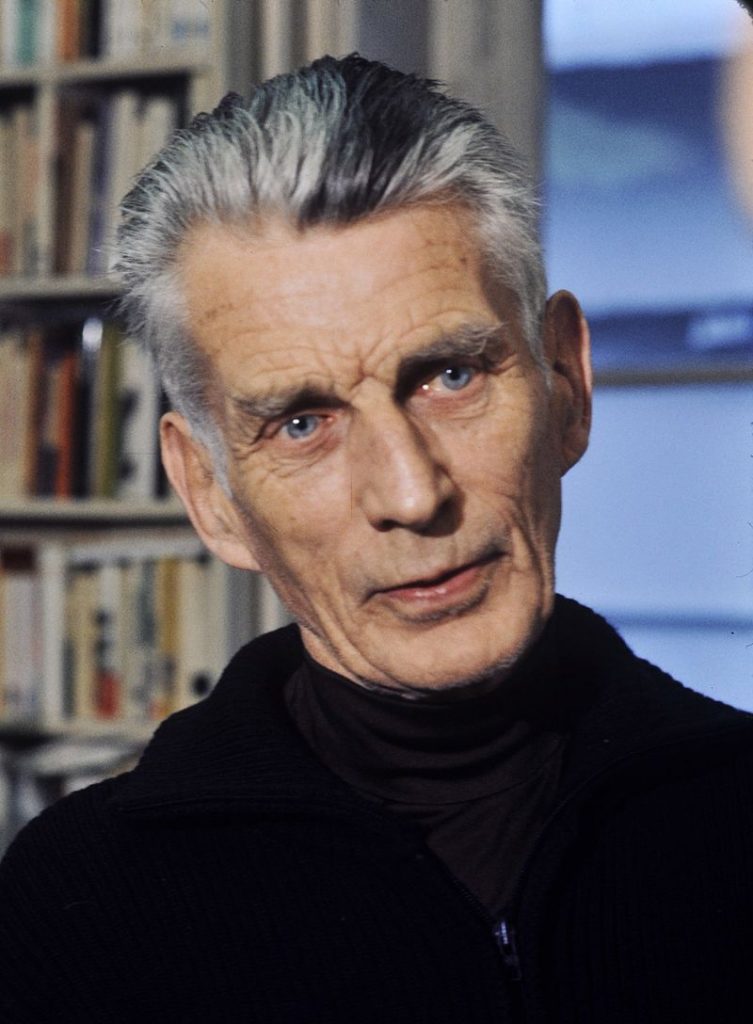

And then there’s Film, a cinematic work by playwright Samuel Beckett. Revisiting Film was the result of watching Turner Classic Movies’ (TCM) airing of Notfilm in July, a documentary on the making of the movie in 1964 during a New York City heat wave. Directed by Alan Schneider and starring silent comedy legend Buster Keaton, the 22-minute movie opens with a brief scene on the streets of NYC before settling into a drab, minimally furnished one-room apartment for the remainder of its running time.

While Beckett, a 1969 Nobel Prize winner, is most known for his game-changing play Waiting for Godot, with its non-specified outdoor setting, many of the playwright’s works utilize a room that both protects and constricts a solitary character. The room in Film was referred to by New Yorker magazine in 1964 as “a small, exceedingly Beckettian room,” but lately its meaning has shifted with world events.

Amy Heller, co-founder of Milestone Films, producer of Notfilm, told TCM, “I have to say some of the paranoia, locked in the little room, seems a little bit like surrealistic kind of imagery rather pertinent at the moment. So, I think it has taken on another aspect as we’re all living in these little boxes, too.”

In explaining Film on the movie’s set in 1964, Beckett told the New York Times, “the picture is about a man’s self-perception.” Keaton also offered his interpretation to the newspaper: “What’s the picture about? Well. I’m not too sure myself. What I think it means is a man may keep away from everybody, but he can’t get away from himself.”

“As a screen character,” Film Comment noted in a 2014 assessment of the actor’s career, “Keaton always knew that a camera was watching him. He covers the lens to protect his wife’s modesty in One Week, throws a kiss goodbye to viewers when he falls off a cliff in The Three Ages, and in the dazzling Sherlock, Jr., he leaves a projection booth and enters into the very movie he has been showing on the screen.”

In Film, Keaton’s character spends most of his time attempting to elude the camera only to discover that hiding from the perception of others cannot change the fact that his perception of himself will never allow him to completely disappear. It’s a small slice of consolation for all of us passing time in the pandemic.