Yellowjacket Conflicts…

...and how to avoid them. It's that time of year—time to watch where you step to avoid painful stings.

Recently we got a new family member, Deuce. He is a dog, a working dog, and a Brittany pointer (they used to be called spaniels). At eight months Deuce is rather young and still trying to understand the world around him. This past week he learned about yellowjackets, a predatory wasp.

We were on our daily morning walk along with three-year-old Hey Mambo Italiano, a more experienced Brittany. About midway through our trek Deuce stumbled on a yellowjacket nest and his reaction was bewilderment and pain. He wasn’t sure what was happening. But when he realized that it was flying insects causing his distress he decided to seek revenge on them. He snapped at them in the air and headed back to their nest’s entrance on the ground.

I did my best to discourage Deuce’s poor decision, grabbing his collar and trying to imitate a running escape. Despite my efforts, the ensuing battle left him with a number of stings, and one persistent wasp nailed me repeatedly in the posterior. Unlike honeybees, yellowjackets can sting repeatedly and also bite with their jaws! I was the unwillful recipient of their full arsenal. Allow me to say it wasn’t very sporting to take advantage of such an easy target as my derrière, but their attack is about protection, not gamesmanship.

Generally when we have wasps’ nests I flag them and stay clear. Yellowjackets are beneficial in gardens and farms because they prey upon insects that damage cultivated and ornamental plants.

But Deuce clearly doesn’t adhere to avoidance, nor does he pay attention to flags. Years ago we had to stop hunting in Pennsylvania when our dog Binx, after an initial row, developed an unproductive vendetta for porcupines. A painful resolve at that, so after three encounters we vowed not to take him into “quill-pig” country ever again. Some festered quills emerged as much as a year later; petting a porcupine quill is an experience not easily forgotten.

August through October is when folks have the most encounters with yellowjackets. At this time these vespids’ colonies are sizeable and they have changed their food preference from proteins to sweets. Outdoor picnics can result in a number of uninvited guests clamoring for watermelon and other sugary foods and drinks. I strongly discourage drinking outdoors from a can between August and mid-October. Use a glass where you can see if you have an unwanted drinking buddy, and look before you sip!

Other things that attract yellowjackets are fragrances like perfumes and hairsprays. Brightly colored clothing is an enticement as well. The Ohio State University Extension service adds a few other interesting odors to the list—“musk oil-based perfumes, heavy body odor, and bad breath, as these smells appear to remind the wasps of skunk, raccoon, and bears that are predators of wasp nests!” Good gravy, could I have been mistaken for a bear?

If you are a true masochist, running a lawnmower over a nest after you have worked up a good sweat is a surefire way to feel the pain.

Swatting at yellowjackets provokes them even further, possibly a good explanation as to why one repeatedly nailed my tush. I can read advice but following it when under fire takes a real pro. That is why I resorted to calling Brown’s Integrated Pest Management. Mr. Brown did not wear any protective clothing when dusting the two nesting sites in our yard, but I noticed that he was deliberate and slow in his motions—coolheaded. He said calm is the key to success: “You have to remain calm or else they will sense your fear and attack.” Wow, wasp Zen. Deuce and I hadn’t a prayer.

So let’s discuss yellowjacket natural history. The scientific name is Vespula maculifrons: Latin-derived Vespula means “common,” macula “spot,” and frons “forehead.”

The first thing to know is that it’s good to be queen. She is the only one who overwinters; all the workers die. In fact, soon after mating in the fall the male dies. The queen will hibernate in a dead tree, or under loose bark, in a burrow, or someplace that gives her cover from cold temperatures. If queens emerge too early a cold snap will kill them.

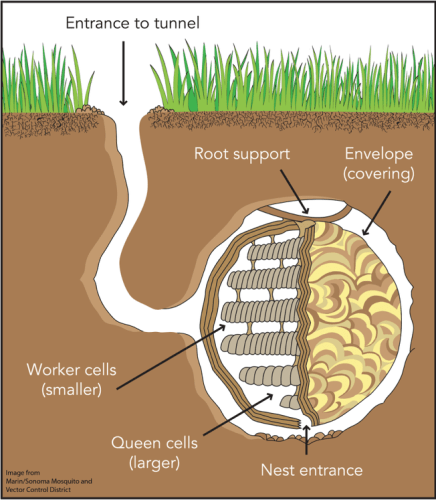

In the spring it is the sole job of the fertilized queen to start off the colony. She begins by building a small nest in an existing burrow, likely excavated by a rodent, or in a hole from a rotted tree’s root. The nest is essentially paper-created by chewing up wood particles and exuding them mixed with saliva. She deposits her eggs in cells within the nest called brood chambers. She feeds the larva for 18 to 20 days and then they pupate and emerge.

Her initial brood consists of sterile female workers. These gals will labor to expand the nest, collecting wood fiber and building chambers, plus they will care for the queen and defend the nest. The numbers will grow between 4,000 to 5,000 workers and 10,000 to 15,000 cells by August or late September. For part of this season the queen continues to lay workers’ eggs. About halfway through she lays fertilized female eggs that will be next year’s queens. They will overwinter and the cycle will begin again. The old queen will die with the onset of cold temperatures.

“What about the males?” you ask. The last generation produces not just the new queens but male drones. They leave the nest and mate with the new queens.

There is an interesting codependency between larvae and adults. Early on the adult workers feed larvae protein-based food—insects, meat, fish, etc.,—and in turn the larvae secrete a sugary substance that the adults eat. The workers prepare the food for the larvae making paste from the proteins. Adults also forage on fruits, flower nectar, and tree sap.

I’ve mentioned that these wasps are beneficial insects. However, depending on your likely interface with them, or if you have a known allergy to their sting, you might make a decision that your situation renders extermination. You can take to the internet for many methods of elimination. I decided to use a service that practices integrated pest management (a topic for another article).

Should you get stung, an ice pack on the affected area at 10-minute intervals can help decrease swelling and pain. Antihistamines can reduce swelling and itching; I gave Deuce a Benadryl.

The Ohio Extension further suggests, “If you’ve been stung more than 10 times, or got stung in the mouth or around the eyes, you should seek medical attention. If you have had an allergic reaction to a yellowjacket sting in the past, or you experience difficulty breathing or swallowing, confusion or slurred speech, tightness in the throat and neck, or weakness leading to fainting, you should immediately seek medical attention at an emergency facility. Persons who have reacted severely in the past should ask their physician for an emergency sting treatment kit.”

Some allergists can provide a series of injections that desensitize an individual to the stings of vespids—a possibility to explore if you have a strong reaction to them. If I have imparted this advice too late to help you, permit me to say that I feel your pain—and may your future be free of unwanted encounters.

Sources

- Animal Diversity Website, Vespula maculifrons

- Ohio State University Extension, Yellowjackets, Dept. of Entomology – Shetlar, Andon, Bloetscher.

- San Mateo County Mosquito & Vector Control District.