Wood Ducks

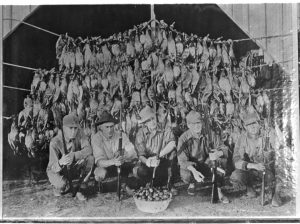

The species was driven to near-extinction by habitat loss and market hunters in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Part of my morning ritual beginning in the middle of May is to check a wood duck box’s contents on my phone. We have a camera in the nesting box that is connected to our Wifi and it can be viewed electronically. One morning in mid-May I noticed a flash of motion in the box. So I quickly opened the camera application on my phone to discover that a female was checking the nest out.

Part of my morning ritual beginning in the middle of May is to check a wood duck box’s contents on my phone. We have a camera in the nesting box that is connected to our Wifi and it can be viewed electronically. One morning in mid-May I noticed a flash of motion in the box. So I quickly opened the camera application on my phone to discover that a female was checking the nest out.

For a number of years I have seen wood ducks debate about using that box. A pair of wood ducks sits on top of it; they take turns looking inside and much discussion ensues. It struck me as surprising that both check out her nesting box, since once the mating period has taken place the male is no longer involved in any family responsibilities. Courtship with a number of males occurs over a few days, but mating is over in seconds. Wood ducks are serially monogamous, meaning they stay with one mate for the breeding season. After mating the male goes to a new territory to molt, or shed old feathers.

One of the funniest things I can recall observing was an exchange by a pair of wood ducks atop a bat house, likely 30 years ago. We had placed it on a tree in our backyard not far from the marsh. It had a black oval emblem near the top, approximately where a wood duck box’s entrance would be provided. A lengthy discussion and inspection took place between the ducks. Each took turns tapping their beak against the emblem. Yes, they even tilted their heads in disbelief. They thought the duck box designers were daft. So we took the hint and provided a proper box for them.

When I relayed the house inspection story to my husband, he gave me a skeptical look, as if my description was an exaggeration. Then about five years later I once again observed two ducks house-hunting. They were in extended discussion about the box, taking turns checking out the interior. This time he got to see the elaborate details of their exchange. “How about that!” he remarked. “I should have known better than to doubt your accounts. They are surely chattering about that house.”

A wood duck lays one egg a day and it is stressful for her, as the eggs she carries make up nearly half her body weight. She doesn’t begin incubation until they are all deposited. This is necessary because the young are precocial, or able to feed themselves and walk about a few hours after hatching. This way they all share the same maturation rate. They will only stay in the box one night before exiting, and the young have been known to leap from nesting sites as high as 60 feet.

During incubation, if she leaves the nest she very carefully covers the eggs with her down. She also has a brood pouch where her neck and chest meet. The underside is nearly bare and supplied with surface blood vessels that transfer heat for the purpose of incubation; her neck is swollen during incubation.

The female incubates for 28 to 37 days. One behavior sometimes adopted by female wood ducks is called intraspecific brood parasitism, or egg-dumping, where they lay eggs in another wood duck’s nest to force other female wood ducks to become surrogate parents. Clutches are normally eight to 15 eggs but dumping could increase this to a number beyond the possibility of successful incubation. Records as high as 40 have been recorded. For the two years that our nest camera caught the exodus, 18 to 24 chicks leapt from the box. Most wood ducks have one brood per season but occasionally two will be reared in more southern areas. The chicks will fledge (fly) in 56 to 70 days.

One year the brood crossed in front of my car when I was returning home. I hustled out to try to film the chicks and the female leapt in the opposite direction away from her young, feigning a broken wing to distract me from her babies. I stuck with them and her efforts became more exaggerated. Finally I did the polite thing and left. This is a defense mechanism used for predators and not uncommon in other species as well.

The wood duck is clearly one of North America’s most beautiful waterfowl. As is commonly the case in birds, the male’s plumage is more colorful than the female’s. The sexes are distinctly different or dimorphic. The male’s head is iridescent green, blue, or purple depending on the lighting, with two distinctive white lines, one starting at the top of the bill and running over the eye and down its crest, and the other beginning at the bill’s lower mandible and extending up to the eye with a lovely curve and then breaking and continuing parallel to the higher white line. Its eye is red and the bill has red accents as well. It has a rusty-colored chest, bronze sides, and a black back and tail. The female is taupe with a lovely teardrop eye-ring; both have light gray bellies. These ducks are approximately 19 inches long with a wingspan of about 28 to 39 inches. In comparison a mallard is about 23 inches in length with a wingspan of 43 to 48 inches.

Monogamous for the breeding season, the lifespan of a wood duck is about four years. Their diet consists of invertebrates and small fish. Adults prefer plants, seeds, and aquatic and land invertebrates. Because they nest in tree cavities, wood ducks are one of the few species of waterfowl with strong claws on their webbed feet, designed for climbing bark. Some other cavity-nesting ducks include bufflehead, goldeneye, and mergansers.

Wood ducks were driven to near-extinction by habitat loss and market hunters in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These waterfowl were especially vulnerable because they roost in groups. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1816 has since protected and controlled bird populations. Hunting regulations and conservation measures, spearheaded by hunters, have been helping wood duck numbers to recover.

An additional factor in the decline of the wood duck population has been the loss of our country’s mature forests. During the Industrial Revolution trees were cut for cordwood to fire the furnaces that ran machines in U.S. factories. Few ancient forests remain in North America; in fact, Bear Swamp is the only primeval forest in southern New Jersey. Urban sprawl has also diminished forested habitat for cavity nesters. Because old forests are rare, larger cavity-nesting birds like wood ducks find it especially difficult to find sizeable trees where they can incubate their eggs. Today conservationists have established manmade nesting box programs to mitigate this loss.

CU Maurice River has constructed a number of nesting boxes for wood ducks and has had some success attracting the species.