Woman Umpire of the 1970s Embraced Only in Bridgeton

Bernice Gera, with Jerry Alden, who was Bridgeton’s Director of Parks and Recreation for decades and essential to the creation of both Alden Field and the tournament.

This year’s story of Jen Pawol, the first woman umpire in Major League Baseball, seems to be one of acceptance, even adulation, and likely success. A similar story of the goal set by Bernice Gera in the 1970s was met by vituperative sexism and unmitigated failure.

Each took an unlikely career path for a woman—to become a professional baseball umpire. One is being hailed now as a symbol of a sport embracing change; the other was condemned almost everywhere as an abomination, a threat to both everything baseball stood for and to women being kept to certain roles. (Now rebranded as tradwife.)

Bernice Gera’s unfortunate road ran directly through Bridgeton, where she found welcoming solace amid the turbulence of her unpopular role.

As part of her determination to become a professional umpire, Gera worked in amateur and semi-pro leagues in various parts of the country in the late 1960s and early 1970s. What better spot to work than the fabled Bridgeton Invitational Baseball Tournament? Dating back to 1967, the Bridgeton Invitational has been one of New Jersey’s iconic semi-pro tournaments. It’s steeped in tradition and known for its speed-up rules. Games were played at picturesque Alden Field.

In addition to high-level competitive games, the Invitational was then known for its prominent guests from across the game.

“Tournament founders, including Jerry Alden, Edgar Joyce, and Ben Lynch would get their agreement then take their cars and go pick them up,” said All-Sports Museum of Southern New Jersey Chair Dom Valella. “We got Joe DiMaggio, Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, Monte Irvin, Ted Williams, Pete Rose, Roy Campanella, and a whole list of celebrities to come down to the tournament.”

Dom Valella, left, chairman of The All-Sports Museum of Southern New Jersey, and Kevin Danna, treasurer, holding a program from the late 1960s for the Bridgeton Invitational, featuring a photo of Bernice Gera, who umpired the tournament regularly for several years.

In 1969, Gera joined the list. While relatively unknown, she did get to be the only guest to participate in the games beyond just throwing out the first pitch. She umpired several contests in tournaments for several years and forged a close connection to Bridgeton baseball and its fans.

Looking back, Gera’s childhood gave her a lifelong love for baseball and imbued in her a desire to help children. She participated in events to benefit children’s charities. During these events, she would get a chance to flex her own baseball muscle, putting on hitting demonstrations with male baseball players, including major leaguer Roger Maris.

A newspaper printed a picture of her with Maris, following a demonstration they put on at Coney Island in 1961.

She hit the newspapers again with Ripley’s Believe It Or Not in 1967, after she was banned from the concessions at Rockaway and Coney Island for cleaning out the prizes in the throwing booths. Her prowess won more than 300 stuffed animals, which she donated to children’s hospitals and charities. “Everything I do in baseball is aimed at helping children,” she explained at the time.

Gera fostered an intense desire to be part of baseball. She contacted every professional baseball team asking for a job—any job. She was rejected or ignored by each one.

She decided to become an umpire.

She went to umpire school, but the facilities didn’t accommodate women. She had to live in a motel 50 miles away. In training, batters would try to hit her with balls when her back was turned. At every chance, the masculine bastion of baseball ridiculed, harassed, and belittled her.

“I got all the curse words in the book,” Gera told reporter Phil Musick of the Pittsburgh Press. “And a lot not in the book. They didn’t want me on the field. It all hinged on whether I could take it. I took it. I kept my cool even though it was disgusting. But after, I’d go home and cry like a baby.”

Umpiring at the Bridgeton Invitational gave Gera a supportive situation when she most needed it. Here, she was accepted as an equal by umpires, players, and fans. While the semi-pro level of play was still not organized professional baseball, she was resoundingly welcomed as the “First Lady Umpire.”

“Jerry Alden, who was involved with the tournament and the Hall of Fame asked her if she’d come to Bridgeton to umpire some games and she obliged,” said Kevin Danna, treasurer of the All-Sports Museum. “She came and she really loved it and she came for a number of years in a row. She was inducted into the Hall of Fame, which cemented the special relationship she had with the Bridgeton Tournament.”

After umpire school, no league would give her a job. She filed Human Rights Division complaints, but baseball appealed when she won. A few congressmen got involved and women’s organizations began to take notice. She filed a $25 million lawsuit against organized baseball. The pressure made the New York-Penn League finally give up and she was hired in 1972.

Gera told Musick her hair had turned gray and patches had fallen out; her legal bills ruined her finances; she got threatening phone calls and letters. Her effort to keep going was waning.

Supporters rallied; opinions now were divided. Gera was honored at a banquet before her first game.

On the day of the game, actually a double header, Gera was filled with doubts about what the future held now that she’d be working with men who hated her, including fellow umpires. She considered not appearing, especially because there was overwhelming press attention.

A cadre of relatives and friends got her to go and she walked onto the field. The first woman to be a professional umpire. Now 41 years old. Pained and exhausted.

***

BERNICE’S FIRST GAME

Courtesy of Fort Lauderdale Historical Society (Initially titled “Lady Blue”)

Expanded and edited for context

Bernice Gera, a petite, genteel lady who lived in Pembroke Pines (Florida), earned a place in baseball history, and with the kind of fame that delights the hearts of true baseball fans. She was the first woman umpire in organized baseball.

On June 24, 1972 Gera was finally assigned to work a game in the minor league Class A New York-Penn League. The strain showed on the face of the 5‘2“ umpire. The game’s other umpire refused even to speak to her as play began in the game between the hometown Geneva Rangers and the Auburn Phillies.

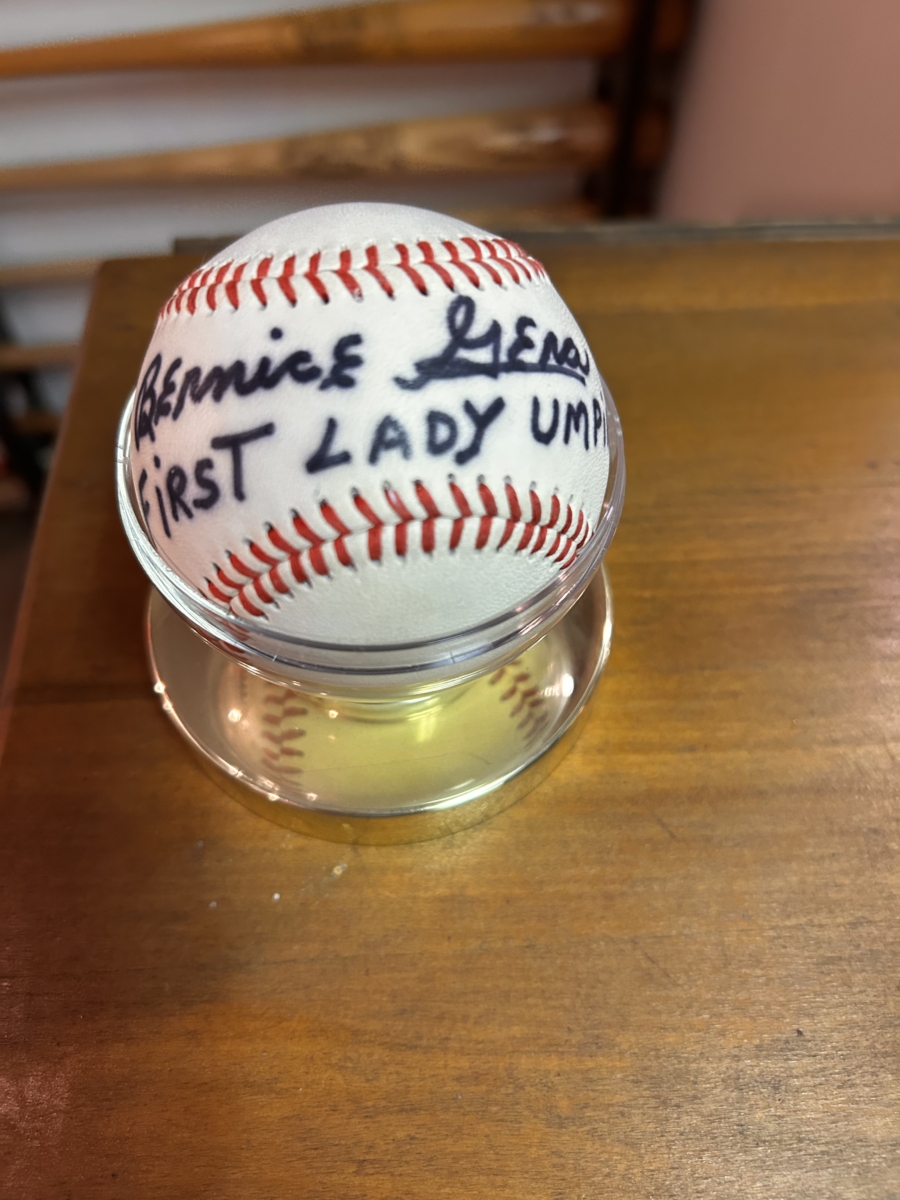

Official tournament baseball autographed by Bernice Gera, “First Lady Umpire.”

Gera/Alden photo, courtesy All-Sports Museum of Southern New Jersey

Nolan Campbell, manager of the Phillies, did speak to her, a lot, and caustically.

In the fifth inning, she blew a call, then reversed herself to set it right. Campbell screamed in her face, “You should be at home, peeling potatoes.” He promptly became the first man ever thrown out of a game by a female umpire. Others picked up the steady chain of epithets, as Gera tried her best simply to do her job.

But, as the game ended, she walked straight off the field and found Geneva general manager Joseph McDonough. She told him she was done. There’d be no second game for her. “I’ve just resigned from baseball. I’m sorry, Joe.” She hurried out of the ballpark, into a waiting car, and away she went, her umpiring career over.

She had made her point and saw no reason to put up with the threats, abuse, and psychological damage. She stayed in baseball, however, continuing to call the semi-pro games. In 1979, she and her husband moved to Pembroke Pines where she worked as athletic director at Colony Point Condominium. Bernice Gera died on September 23, 1992.

***

LATER YEARS

(Reported by Dave Anderson, Miami News)

“Baseball fought me for years,” Gera said. “In my heart I feel they truly went out of their way to hurt me because I am a woman.

“People have been calling me a quitter, but if I was a quitter I never would have fought it so long,” she declared. “I’m just frustrated and disappointed in baseball. My whole life has been baseball… I would have shined the ball players’ shoes if they had let me.

“In a way, they succeeded in getting rid of me,” she said. “But in a way, I succeeded too. I broke the barrier. It can be done. I don’t care what people say now. People haven’t gone through what I’ve gone through. You must experience it to understand it.” —M.B.

END NOTE: Bernice Gera so much appreciated the chance that Bridgeton gave her to simply be an umpire, in her will she stated she wanted some of her ashes buried behind third base at Alden Field. Her request was granted.

Portions of this article are adapted from work by the Society for Advanced Baseball Research (SABR).