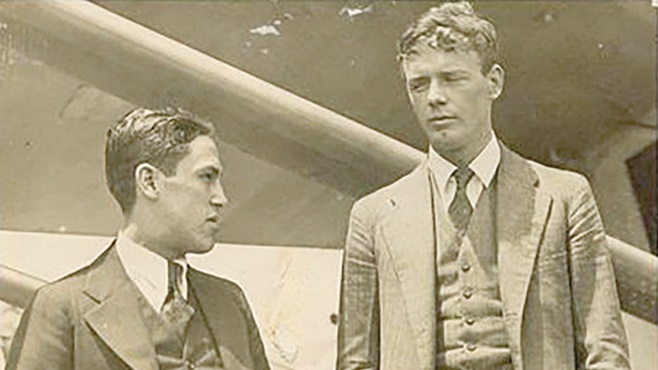

Two Pilots

Mexican aviator Emilio Carranza and Charles Lindbergh each had a fateful connection to New Jersey.

The stone monument juts out as if an extension of the earth, sitting solitarily in an isolated clearing. Missing are the usual landmarks and signposts expected to clarify a location, but this spot is a mere pinpoint within the wide expanse of the New Jersey Pine Barrens. The monolith is, concurrently, a commemoration, a tribute and a symbol and is already into the ninth decade of its role in the annual ceremony conducted by the Mount Holly American Legion Post 11 to honor a man the writer Joan Didion might have said was lost to “history.”

That man, Emilio Carranza, was an aviator and captain in the Mexican Air Force, and the New Jersey Pine Barrens was an unanticipated last stop in his final journey as a pilot.

Carranza became a traveler at an early age. Born Emilio Carranza Rodriguez in Villa Ramos Arizpe, Coahuila in 1905, he moved with his family in 1911 to San Antonio, Texas during the upheaval of the Mexican Revolution. Three years later he was back in his home country as the grand nephew of the new Constitutional President of the Mexican Republic, Jose Venustiano Carranza, whose death in 1917 prompted a return to the U.S. and a temporary life in Eagle Pass, Texas.

During his time in Mexico, Carranza developed an interest in aviation that would soon become a passion. According to an account of his life written by a second cousin, Ismael Carranza, he “hung around every day at the Balbuena airport with his uncle General Alberto Salinas Carranza. His inquisitive spirit and observing mind made him mix among pilots, mechanics, technicians and airplanes; without missing any details he learned from all of them. This is where his vocation as a pilot started but he had to wait some years until he could qualify age wise, to meet the requirements…”

By the time of his family’s return to Mexico in 1923, Carranza was committed to flying, having been accepted into the Military School of Aviation. Upon graduation, he set his sights on long-distance flight, selecting a decommissioned plane from the Air Force and supervising its restoration. He christened it Coahuila and, on September 2, 1927, successfully undertook the first nonstop flight from Mexico City to Juarez.

Despite having flown 1,000 miles to set a record, Carranza remained in the shadow of American aviator Charles Lindbergh, whose May 21-22, 1927 solo nonstop transatlantic journey from Roosevelt Field in Long Island to Le Bourget Aerodrome a few miles outside Paris was the first such flight in history, logging in at 3,610 miles. It’s reported that Carranza had earned the nickname “the Mexican Lindbergh,” which determined that the two were destined to meet.

Immediately following Carranza’s Mexico City-Juarez flight, the American aviator, who had touched down that very day in Texas, met with the Mexican pilot at a reception in El Paso, an encounter that is purported to have initiated a good friendship.

By December 1927, Lindbergh set the second longest nonstop extended flight record by traveling from Washington, DC to Mexico City on a goodwill mission and reuniting with his new friend.

In 1928, the year Carranza set a record for the third longest non-stop solo flight with his 1,575-mile journey from San Diego to Mexico City, a Mexican newspaper published a photograph of the two (see above), a dual portrait of aviators dressed handsomely in three-piece suits, their personalities on view. Lindbergh’s recent global fame seems to provide permission to fully acknowledge both the the camera and the moment, but Carranza, clutching a hat in one hand and a cigarette in the other, is unassuming, deflecting attention from himself as he looks away from the lens and directly at his U.S. counterpart.

Next Week: New Plans