Survivor Stories

University project seeks Holocaust survivors—including Vineland chicken farmers—to tell their stories for a digital exhibition.

The Sara and Sam Schoffer Holocaust Resource Center at Stockton University is looking for area Holocaust survivors and their family members for a major new project to compile and create a digital archive on the lives of Holocaust survivors who settled in South Jersey.

The “South Jersey Holocaust Survivor Digital Archive and Exhibition” will focus on survivors from Cumberland, Atlantic, and Cape May counties. Stockton faculty, staff and students are identifying and interviewing survivors and/or their family members, and reviewing memoirs written by survivors through the center’s Memoir Project.

Some 250 area survivors have already been identified, and about 20 have been interviewed through Zoom since the spring, said Gail Rosenthal, executive director of the Holocaust Center.

“It is essential that we collect the documents and testimonies now,” said Associate Professor of History Michael Hayse, who is curating the project. “The number of Holocaust survivors who are still with us is quickly dwindling. Several local Holocaust survivors have passed away since we started the project seven months ago.”

The archive and exhibition will be an enduring resource for students and the public to learn about the history of the Holocaust and Jewish life in Europe before World War II. One often overlooked aspect of this history concerns the months and years many survivors spent as refugees, or in the parlance of the time, as “Displaced Persons” (DPs) after World War II.

The archive and exhibition will be an enduring resource for students and the public to learn about the history of the Holocaust and Jewish life in Europe before World War II. One often overlooked aspect of this history concerns the months and years many survivors spent as refugees, or in the parlance of the time, as “Displaced Persons” (DPs) after World War II.

The project will also focus on several topics of special interest to our region:

• Immigration to the United States. Many Holocaust survivors first lived and worked in major metropolitan areas, especially New York City, before coming to South Jersey. The exhibition will explore how they navigated the transition to a new country, a new language, and new customs.

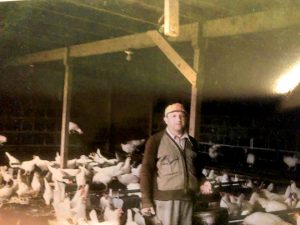

• The Jewish Chicken Farms of South Jersey. A large number of local survivors first came to the region because of the opportunity to own and operate chicken farms. By the mid-1950s, there were dozens of egg and poultry farms in South Jersey owned by Jewish survivors of the Holocaust, with large clusters of farms in Millville, Vineland, Oceanville, and Egg Harbor Township. (Read about Vineland chicken farmers Harry and Sonia Golubcow on facing page.)

The work on the chicken farms was hard, and the financial reward was limited. Changes to the egg and poultry industry forced most small family-owned poultry farms in the United States out of business by the mid-1960s, including the Jewish farms of South Jersey.

A special traveling exhibition on the “The Jewish Chicken Farms of South Jersey,” is being created by Allison Kisielis, a graduate student in the Master of Arts in Holocaust and Genocide Studies program. It is scheduled to debut in summer 2021 and will also go to schools, historical societies, libraries, and other sites in South Jersey.

• Contributions to Southern New Jersey. Holocaust survivors and their families became pillars of the region’s economy, culture, and society. As they moved off the chicken farms, many bought or established businesses in the hospitality industry, real estate, retail, commercial fishing, and other fields. Because they invested in their children’s education, the Second Generation and beyond have further expanded businesses, and have gone on to other careers in law, medicine, education, and much more. The Exhibition will highlight these individual stories.

Hayse said computer stations in the Holocaust Center will allow students and visitors to learn about the Holocaust through the eyes of survivors. Some information will also be available online.

Rosenthal said the completed interviews have led to identifying more survivors and their families.

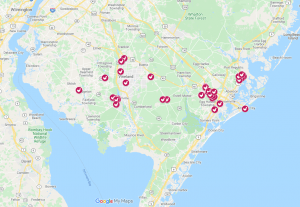

She said students and student interns will be actively involved in creating the project and one major project is creating an interactive map of all of the Jewish-owned chicken farms for the exhibition.

The center sent letters out in the spring inviting area survivors or their family members to participate, but Rosenthal said she knows there are more who have yet to be identified.

“People we talk to keep leading us to more people,” she said. “We want to tell their stories, to show how they survived, kept going, and contributed to life in South Jersey.”

Leo Schoffer, a member of the executive committee of the Holocaust Center, and the son of Holocaust survivors for whom the center is named, said the new project will complete the connection between the center and the community that was central to its development.

“South Jersey offered an opportunity for survivors to settle here and begin a new life after they were evicted from their ancestral homes,” Schoffer said. “It is a very special story. The center is preserving their names and histories so future generations can better understand who they were, why they came here, and their connections to the community.”

Anyone with information can contact Rosenthal at the Holocaust Center at 609-652-4699 or at [email protected].

* * * *

Two Stories of Survival

Gerschon (Harry) Golubcow was born to Mendel and Gitla Golubcow on December 25, 1905 in Miory, Poland. Gerschon was 34 years old with a wife and young son when WWII broke out in September 1939. Shortly after Nazi occupation reached Miory, Gerschon and his family were forced to live in the Miory ghetto.

In 1942, Gerschon and his son survived the ghetto liquidation and the Einsatzgruppen, mobile killing units that murdered many of the Miory ghetto Jews en masse. Gerschon found shelter with a sympathetic Polish family who hid him underneath their floorboards. His son found temporary shelter with a Polish woman, but when he was forced to move to another hiding place in a nearby town, he again faced the Einsatzgruppen and did not survive.

After 18 months in hiding, Gerschon decided to join a partisan group and he remained with them until the end of the war. At war’s end, Gerschon returned to Miory.

Sonia Estrov Golubcow was born in Miory, Poland on September 27, 1919 to Zalman and Nechama Estrov. She was the fourth of six children. Growing up in Miory, Sonia was surrounded by a very religious, Jewish orthodox community and often experienced anti-semitism. At age 14, Sonia left Miory to work for her relatives’ grocery store in Vilna, where she spent the majority of her time until WWII broke out.

Upon returning to Miory, Sonia was assigned work at a post office in Plesa, 70 miles east of her hometown. In June 1941, after the Russian-German non-aggression pact was broken, Sonia was able to escape the approaching Germany army by taking on a job herding cows, which enabled her coworkers from the post office to travel farther east to saftey. When Sonia’s group arrived at their destination in December 1941, she was assigned to work duty collecting sticks in the forest and then in a grocery store, where she stayed until the end of the war.

When Sonia returned to Miory in the spring of 1945, she found very few surviving relatives. Harry Golubcow, who was married to her cousin prior to the war and was now widowed, also returned to Miory. They both wanted to emigrate, and they decided to marry and leave Miory together. By 1946, the pair settled in Bad Reichenall DP (Displaced Persons) camp, where they had a son, Saul.

With the help of a cousin, they emigrated to the United States in 1949 and lived in the cousin’s basement in Brooklyn, NY for three months. With the help of a friend and assistance from HIAS, the family moved to Vineland, NJ where they purchased a chicken farm in July 1950. They worked on the farm for 17 years and had a second child, Molly. In 1967, the Golubcow’s moved on to the hotel business and owned the Seacrest Hotel in Atlantic City, NJ for 10 years before retiring and moving to Rockville, MD in the early 1980s. Harry passed away in 1986, Sonia in 2018. Sonia and Harry are survived by their two children and three grandchildren.