Seabrook on Film

A documentary about past Seabrook communities is in the works; Cumberland County residents are invited to share memories for the film.

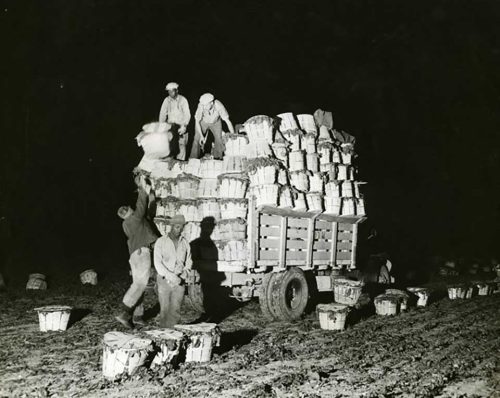

From 1940 to 1960, Seabrook Farms, the Upper Deerfield Township manufacturer specializing in frozen vegetables, ruled the agricultural world in volume and sales and amassed for its owner, Charles F. Seabrook, a reputation as the “Henry Ford of Agriculture.” This month, filming will resume in Cumberland County for The Paradox of Seabrook Farms, a documentary by European director Helga Merits about the Seabrook family, their workers and their empire.

Merits, a newspaper and radio journalist in Holland and Belgium before turning to historical documentaries in 2005, said the idea for a film on Seabrook Farms began in 2018.

“I was in Boston for the celebration of the Baltic Film Festival where a documentary film that I had made was screened,” she told SNJ Today in a recent interview. “This was about a refugee camp in Germany, where after WWII, some 4,000 Estonians lived. They made the camp into an Estonian village, not only with schools and workshops, but also with a theater, choirs and even a tourist bureau.”

After the screening, she was approached by “a group of about 10 people” who shared a similar experience of growing up in Seabrook, New Jersey. “It was the image of a tightly knit community, consisting of many smaller but different communities, which made me enthusiastic, and I decided then, in Boston, that I wanted to make a film about it,” she said.

In 1978, the New York Times chose to sum up the Seabrook Farms story as “3,000 employees in a vast plant, the biggest processing business in the world and town of its own…” Those 3,000 employees ranged widely in culture, from Caribbean migrants, displaced Estonians and previously interned Japanese Americans to Southern Blacks and Appalachian whites. Their stories comprise one thread of the documentary.

“There are a lot of people who had to face injustice—and there still are—and who had to cope with this themselves, without any help or support,” said Merits. “There are a lot of stories we do not hear about which are of small-scale heroism and about helping one another. These are not about big heroic deeds, but small ones, and so important, because these small heroic deeds, are, I think, essential for our belief in humanity. These are the stories, I think, which are so worthwhile showing, because we can learn a lot from these.”

“There are a lot of people who had to face injustice—and there still are—and who had to cope with this themselves, without any help or support,” said Merits. “There are a lot of stories we do not hear about which are of small-scale heroism and about helping one another. These are not about big heroic deeds, but small ones, and so important, because these small heroic deeds, are, I think, essential for our belief in humanity. These are the stories, I think, which are so worthwhile showing, because we can learn a lot from these.”

A second thread of the documentary concerns the Seabrook family, whose story is characterized on the film’s website as “a Greek tragedy of betrayal.” According to Merits, “It seemed, or so I understood, that C.F. Seabrook wanted his company to be a family business to be passed on to the next generations,” noting that Seabrook’s sons were well-educated and given the responsibility for much of the work on the farm and in the plant.

“But then distrust crept in and he sold the company, which went bankrupt some years later,” she said. “So, the initial promise of the father to his sons turned into a rejection of the sons. Who betrayed whom is a question which father and sons would have certainly answered in different ways.”

“But then distrust crept in and he sold the company, which went bankrupt some years later,” she said. “So, the initial promise of the father to his sons turned into a rejection of the sons. Who betrayed whom is a question which father and sons would have certainly answered in different ways.”

The threads of the Seabrook family and their workers constitute the paradox of the film’s title. As the director explained, “The communities working at Seabrook Farms were mostly poor but had each other. The parents worked hard so their children could have more and maybe better possibilities than they had. The trust, which was missing within the Seabrook family, which would have enabled the continuation of Seabrook Farms, was within the families who worked there.”

Merits admitted that three documentaries could be made from the Seabrook Farms story, one about the various communities that formed the village of Seabrook today, another about the Seabrook family and a third on “the history of agriculture and the influence of World War II upon the farmers and their way of working.”

The documentary has a projected release date of early next year, but the completion of filming and post-production are only two factors in wrapping up the project.

“There is the question of funding,” Merits added. “Working on a film means to spend a lot of time trying to get the necessary funding. This is not a commercial film, but a historical documentary and hopefully one which can be used for educational purposes. Finding funding for documentaries is rather difficult and we are still trying to find the necessary funds to be able to finish the film.”

“There is the question of funding,” Merits added. “Working on a film means to spend a lot of time trying to get the necessary funding. This is not a commercial film, but a historical documentary and hopefully one which can be used for educational purposes. Finding funding for documentaries is rather difficult and we are still trying to find the necessary funds to be able to finish the film.”

During her 2019 visit, a “meet-and-greet” event was held at the Seabrook Educational and Cultural Center, a museum preserving the stories of the various cultures that comprise the town. “There were around 40 people of different communities willing to share their stories,” she recalled. “The Center itself was interesting to see as you can read and see there the history of the different communities who came to Seabrook Farms.”

During her 2019 visit, a “meet-and-greet” event was held at the Seabrook Educational and Cultural Center, a museum preserving the stories of the various cultures that comprise the town. “There were around 40 people of different communities willing to share their stories,” she recalled. “The Center itself was interesting to see as you can read and see there the history of the different communities who came to Seabrook Farms.”

Looking back on that first trip here, she commented, “What stands out for me is that, despite the fact that it was the Japanese-American community who created the museum, the other communities are represented as well. The coming together of different communities is interesting and important, because most museums are focused on only one community.”

Share Your Memories of Seabrook Farms

Later this month, Helga Merits, pictured, will be in Cumberland County to record interviews with those she has already contacted. She then plans to “to drive around, see what is interesting or even necessary to film.”

Later this month, Helga Merits, pictured, will be in Cumberland County to record interviews with those she has already contacted. She then plans to “to drive around, see what is interesting or even necessary to film.”

On Saturday, April 22, she will be at the Bridgeton Public Library where she hopes “to meet people who have either grown up at Seabrook Farms, or heard stories about it, or had friends who were growing up there and who are willing to share their memories, perhaps pictures or documents.

“Who knows, someone might still have original film material about Seabrook Farms.”

Learn more at meritsproductions.com or e-mail Merits at [email protected]