Red Velvet

The lovely blossoms of the cardinal flower in September. Note flower blossoms emerging upward from a spikey stem.

Photos: J. Morton Galetto

The velvety red cardinal flower has a rich history to note as you view its showy display in gardens and natural areas.

When we motor along the shores of the Maurice River toward the end of summer, and sometimes as late as October, the blossoms of the showy cardinal flower often catch my eye. When there is a patch of plants, you are often able to see them at 200 or more feet away.

The velvety red flower’s name is associated with the brilliant red of the College of Cardinals, known as the electoral college for the papacy, which is composed of all the cardinals of the Catholic Church who select the pope. It seems a fitting time to address the flower as it has just put on a nearly two-month show, just a few months after the selection of the first American pope. Cardinal flower’s Latin name, Lobelia cardinalis, also has connections to a Flemish botanist, Matthias de l’Obel (1538-1616), as do all the lobelias.

There is another widespread plant in the same family called great blue lobelia, or Lobelia siphilitica, that has purplish-blue flowers. Mapping shows it to be in our state but I’ve not noticed it. Hobbists and scientists post their sightings to an application called iNaturalist, but no reports have occurred in Cumberland County; indeed, very few have been noted anywhere else in southern New Jersey.

The blossoms of these flowers extend most of the length of the plant’s two- to four-foot spikey stalk. They open starting from the bottom, where there are the most blooms, and continue to spread to the top. Five petals make a corolla—or a platform of sorts—that attracts pollinators to the nectar. Because of the flower’s tubular shape, which connects the stigma to the ovary, many sources suggest it is reliant on hummingbirds’ long bills for pollination. However, butterflies are attracted to the blossoms as well and are able to reach into the tube, and bees also frequent the flowers, so I suppose they too play this role. Moths with long proboscises may possibly aid in pollination as well.

In southern New Jersey regions, seven species of moths make use of cardinal flowers; these include Ennomosia basalis, pink-washed looper, plevie’s aquatic, greater black-letter dart, greater spotted cutworm, red-banded leafroller, and dark-spotted palthis. Birds are especially reliant on moth larvae for food.

The Chesapeake Bay Program describes the flowers as tubular with two lips and three lobes. Based on this description, I would say the lobes look like a three-pointed tongue sticking out beneath two lobes of an upper lip that resembles a Salvador Dali mustache. Above the lips and the lobes is the stigma, which looks like a periscope, topped off by a white ball. The stem beneath the bloom has numerous dark green leaves. It retains mounds of basal leaves after blooming.

Cardinal flower prefers partial or full shade but will tolerate sun if the soil is consistently wet. It is often found in wet woods and meadows. I’ve seen it growing locally on sandy spits where the river deposits silt into Millville’s Menantico Ponds Wildlife Management Area. Here it is lapped by wind-driven wave action in full sun.

When patches of cardinal flower have multiple plants it can be seen at great distances.

This herbaceous perennial is a showy addition to any native wildflower garden and its popularity is undeniable. The North Carolina Extension service voted it North Carolina’s Wildflower of the Year in 1982, 1983, and 2001.

The University of Maryland Extension service suggests plants that make good “garden companions” with Lobelia cardinalis: sensitive and cinnamon fern and mistflower in moist areas and woodland sunflower, black-eyed Susan, and whorled coreopsis on slightly higher ground. As the name suggests, “garden companions” means these plants like similar soils and moisture levels and therefore they grow well together.

Cardinal flowers are widespread in North America, and in fact in the United States only seven states along our northwestern border with Canada show it to be absent (Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and North and South Dakota). It grows in coastal, mountain, and piedmont regions. The provinces of Canada that host Lobelia cardinalis are Ontario, Quebec, and mainland New Brunswick; additionally it is found in Mexico, Central America, and Colombia.

Native American ethnobotany records show the Cherokee, Delaware, Iroquois, Jemez, Meskwaki, Pawnee, and Zuni tribes used parts of cardinal flower for medicinal purposes. Lobelias have long been gathered in various forms for venereal diseases, and it was also chosen for treating stomachaches, typhoid, worms, rheumatism, and notably was used as love potions. It played a part in ceremonial rain dances and as protection against witchcraft. Pawnee, Meskwaki, and Iroquois used combinations of roots and flowers as a love charm. Medical Plants of North America warns, “This is a very potent and potentially toxic herb. Do not experiment with it.”

Although I’ve not experimented with nibbling on its roots or flowers, it was still love at first sight.

Sources

Arkansas Native Plant Society, Know Your Natives – Cardinal Flower. Sid Vogelpohl

University of Maryland Extension, Cardinal Flower. Extension.umd.edu

U.S. Forest Service, Plant of the Week, Cardinal Flower, by Larry Stritch.

NC State Extension, Lobelia cardinalis.

Medical Plants of North America, Jim Meuninck, 2008/2016.

Native plant finder, National Wildlife Federation, University of Delaware, and U.S. Forest Service for moths attracted to cardinal flowers.

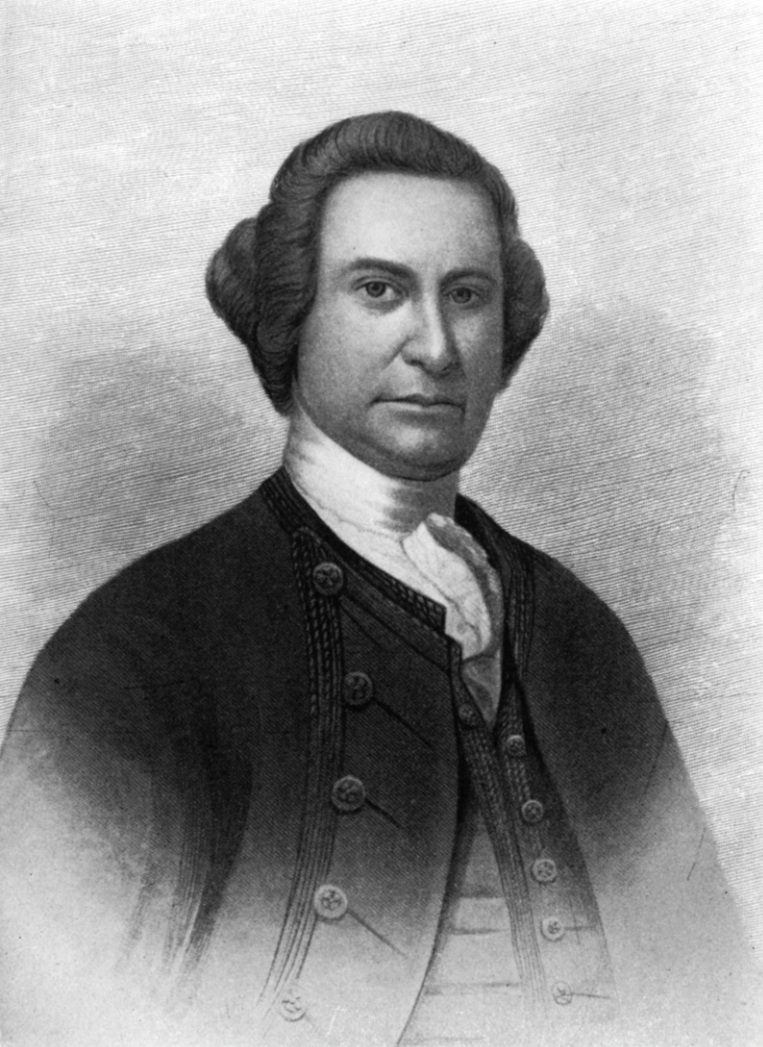

Portrait of Sir William Johnson 1763, based on a lost portrait by Thomas McIlworth.

Of Note, Historically

“Sir William Johnson, superintendent of Indian affairs in North America from 1756 to 1774 and a friend of the Iroquois, sent samples of the blue flower (Lobelia siphilitica) to England, hoping to provide Europeans with a long-sought cure for syphilis, then a fatal disease. But the English trials of the plant had negative results and European physicians had to discount it as a cure for syphilis. Nevertheless, the Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus labeled the plant Lobelia siphilitica,” (“Magic and Medicine of Plants,” c. 1986 published by Readers Digest Assoc.).