Precious Pinelands: Part 2

Cranberry farms have existed in the Pinelands since the mid-1800s, but the fruit was gathered by indigenous peoples long before. The modern way to harvest cranberries involves flooding the bog, then skimming with water wheels. Photo: Leslie M. Ficcaglia

How a region’s natural and cultural resources were protected—and the challenges that lie ahead.

By Leslie M. Ficcaglia, CU Trustee Emeritus and former Pinelands Commissioner

When the National Parks and Recreation Act was passed in 1978, including legislation for the Pinelands National Reserve, the text directed the planning entity to develop a Comprehensive Management Plan (the CMP) to guide protection and development in that area. Gov. Brendan Byrne appointed Franklin Parker to be the first chairman of the Pinelands Commission. Candace Ashmun, called “the Godmother of the NJ Pinelands,” was among the first members, and Terry Moore was the first executive director. This was the group that, with the help of Michael Catania and a number of others from both the legislative branch and the governor’s office, was instrumental in creating the CMP.

John McPhee’s book The Pine Barrens became required reading for the senators and assemblymen who were asked to approve the plan. The phrase “Preserve, protect, and enhance” became the guideline that enabled the Commission later on to do virtually anything it wanted within the context of the law.

At a retrospective symposium in 1987 in which key players came together to discuss the process, Ashmun observed, “… I remember … everybody having a sense of humor, which has been crucial for these long years. Without a sense of humor, maybe we would all have gone mad.” She also noted, “We finally had a bunch of public hearings on solid waste disposal and suddenly we became everybody’s hero. That was the most rewarding time of all. But it is an issue … that we will all have to remember, because the Pines has nobody in it, and I say that in quotes. But it’s really right there waiting for somebody to use as a dump.” (pp. 46-47 https://governors.rutgers.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/BTB-10-15-87Pinelandscolloquium.pdf)

Terry Moore commented that, very early on, few people understood the importance of the Pinelands plan “as a land use measure that is now being borrowed for lots of other areas of the country.” (p. 47 https://governors.rutgers.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/BTB-10-15-87Pinelandscolloquium.pdf)

Since that time the task of the Commission, its staff, and the Commissioners has been to weigh each application to develop or make changes in the Pines based on the requirements of the CMP. The primary concern has been the 17 trillion gallons of potable water that lie beneath the surface of the Pinelands, and protecting that resource for future generations. Also, the fact that this area is habitat for a large number of common and rare plants and animals—many of which are on the threatened or endangered lists—makes its protection a life-and-death concern for these species. In addition, the Pinelands encompasses a way of life that is important to our history as well as our present-day culture. Blueberry and cranberry farming are two of the most iconic.

Duck hunter on a Pinelands stream. Photo: Leslie M. Ficcaglia

Native Americans and the early settlers gathered wild blueberries and cranberries and made them an important part of their diets, whether eaten fresh or dried and preserved. However, the blueberry as we know it today had its start in 1906, when Dr. Frederick Colville began trying to create a better cultivar from the native varieties. Elizabeth White, daughter of a local cranberry farmer, heard of his work and invited him to pursue his experiments on her father’s land. Her interest was in the development of a variety that could produce berries large enough to become a significant crop on her father’s farm, Whitesbog, in Pemberton Township, Burlington County. She assisted in Colville’s efforts by asking locals to look for bushes with bigger berries, offering money for the largest fruit and naming each variety after its discoverer. Dr. Colville developed thousands of plants from the best bushes, and in 1916 the first crop from the new cultivars was offered for sale. Blueberry farming soon became a staple for farms endowed with the acidic soil that the fruit prefers. Fresh blueberries are still a major crop in New Jersey and, nationally, the state is a leader in its production.

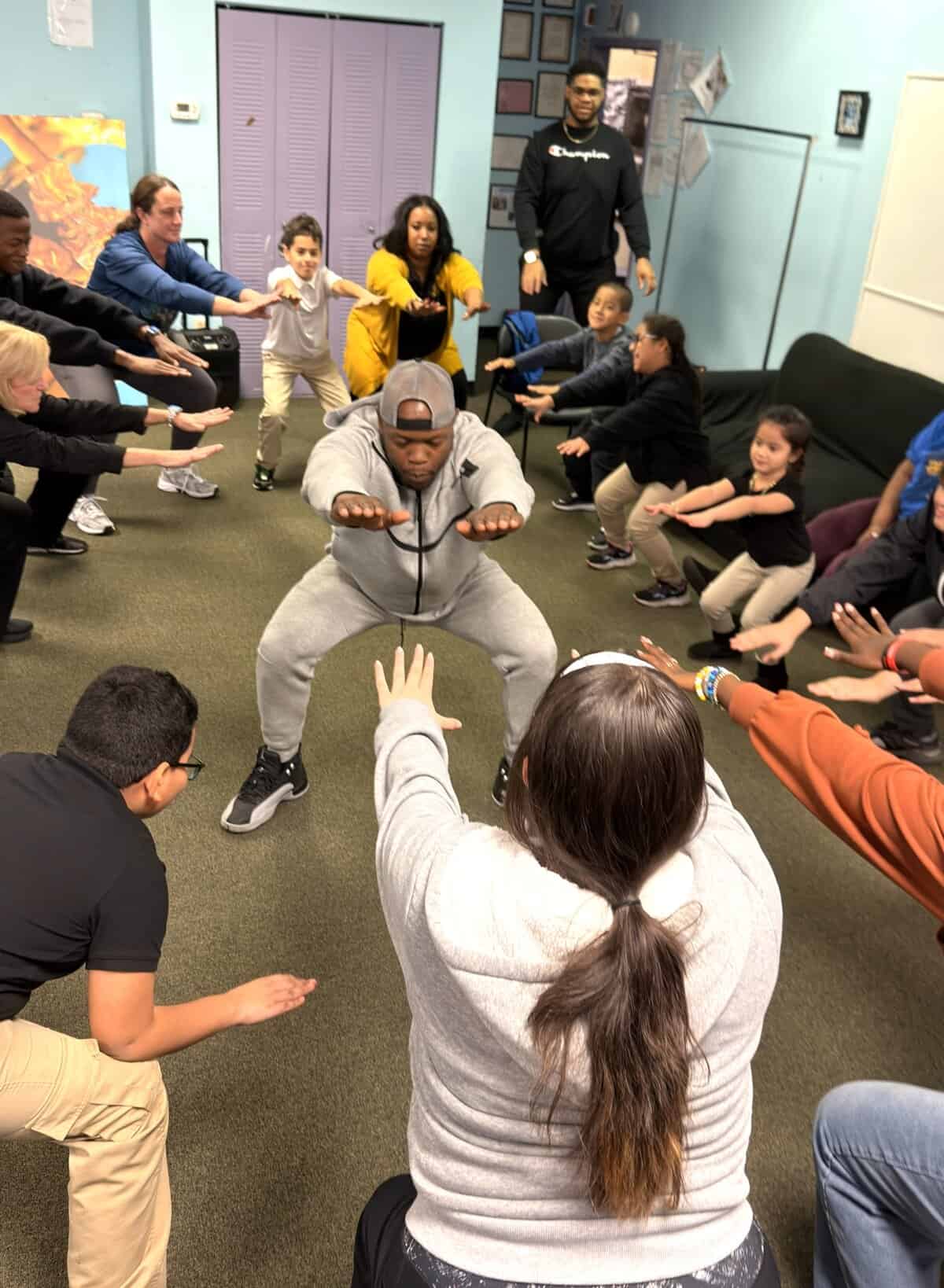

American Indians used the cranberry not only for food but also for medicine and clothing dye. Its name comes from the Pilgrims, who were reminded of the head of a crane by the fruit’s pink flowers. They called it “craneberry,” which was later shortened to “cranberry.” In New Jersey cranberry farming was first attempted in the mid-1800s in a bog near Burrs’ Mills in Burlington County. Other shallow ponds were developed where water was naturally available, and some of the initial sites are still producing on wetlands worked by descendants of the original farmers.

Although once gathered painstakingly by hand, cranberries have been harvested by the wet-picking method since the 1960s. A machine with a water reel is driven through the mechanically flooded bogs, knocking the berries off the vines so that they can be gathered as they float on the water. They are then sorted and shipped to a processing plant to be made into sauce, juice, and other products.

Historically the Pinelands was home to a number of other occupations traditionally associated with the area. Sawmills dated back to 1700 and several are still active. Charcoal making was common from 1740 to 1960. Initially it was part of the process of smelting bog iron, but after 1850 it was used as fuel for both heating and cooking. However, at the end of the 19th century many Pinelands residents were left without jobs when rural industries such as glass, iron, cotton, and papermaking failed. Some fell back on “working the cycle,” taking advantage of the seasonal resources of the forests, plains, and coastal areas. Hunting, fishing, gathering, trapping, lumbering, and boatbuilding—especially the small sneakboxes and garveys used for shellfishing and waterfowl hunting—were among the occupations that people turned to as a livelihood.

The Richard J. Sullivan Center at the Pinelands Commission offices in Pemberton, which opened in December 2001, showcases Pinelands history, geography, and biology at The Candace McKee Ashmun Pinelands Education Center, unveiled December 14, 2018. It features more than 400 square feet of displays, a 90-gallon aquarium with native Pinelands fish, a terrarium with carnivorous plants, and dozens of Pinelands artifacts. Well worth a visit, it is open Monday through Friday from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. For groups larger than 10 people, contact the Commission’s Public Programs office to arrange an appointment.

Candace McKee Ashmun, “Godmother of the Pine Barrens.” Photo: Leslie M. Ficcaglia

The Pinelands has a rich cultural history and its woodlands and plains provide habitat for a significant number of rare flora and fauna. It is truly a New Jersey treasure and should be protected for future generations. Its fate is in the hands of both the government and the people, who hopefully will make the right choices to sustain it.

Sources

New Jersey News: Remembering Candace McKee Ashmun: https://newjersey.news12.com/remembering-candace-mckee-ashmun-the-godmother-of-the-new-jersey-pinelands-42190922

The Pinelands Protection Act: A Discussion by Participants in the Process: https://governors.rutgers.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/BTB-10-15-87Pinelandscolloquium.pdf

Pinelands Preservation Alliance website: https://pinelandsalliance.orghttps://pinelandsalliance.org

Pinelands National Reserve website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinelands_National_Reserve

State of New Jersey Pinelands Commission website: https://www.nj.gov/pinelands/cmp/summary/

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Leslie M. Ficcaglia was the founding chair for the board of Millville’s Riverfront Renaissance Center for the Arts. She retired from her profession as a psychologist in 2000. But she is best known for her environmental activism for which she is listed in Who’s Who in America. Her ecotourism brochure was distributed by Maurice River Township and became the impetus for her first website about the Wild and Scenic Maurice River. She worked on the task force to obtain federal Wild and Scenic status for the Maurice River and its tributaries.

Leslie served as a member of the Maurice River Township Planning Board for almost 20 years and as its chair for seven years; she was vice-chair of the Cumberland County Planning Board until 2007.

For 18 years, Leslie was the Pinelands Commissioner for Cumberland County, serving for a number of years as chair of its Personnel and Budget committee. She is a past trustee for the Association of New Jersey Environmental Commissions. She also served on the county Tourism Council, has chaired the Maurice River Township Environmental Committee, acted as trustee for Citizens United to Protect the Maurice River; and was a member of the Delaware Bayshores Advisory Council of The Nature Conservancy.

Leslie received the 2003 federal Environmental Protection Agency’s Region 2 Environmental Quality Award for Individuals for contributing to the protection of natural resources in the Southern New Jersey Delaware Bayshore Region and Pinelands Preserve.

Having lived on the Manumuskin River for many years on a farm that she and her late husband Anthony tended, Ficcaglia currently resides in southwestern France in the foothills of the Pyrenees.