Historic Journey

Local residents travel to Washington, DC, to learn about the African American journey in America.

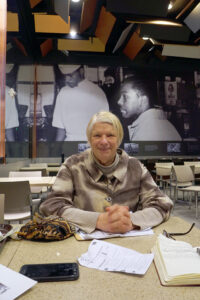

On February 27, a group of gallant travellers from our area, braved frigid temperatures and blustery winds to take a journey to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, DC. The trip was sponsored by members of the South Jersey Holocaust Coalition.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), which opened its doors in the autumn of 2016, is the latest museum to be built on the Smithsonian National Mall.

Other National Mall museums and attractions include the National Air and Space Museum, the National Museum of the American Indian, and the National Museum of Natural History.

The NMAAHC was established to reveal the rich, educational, painful, inspirational, and enlightening experiences of Americans of African descent throughout the history of the United States, to all.

According to its website, “The National Museum of African American History and Culture is the only national museum devoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life, history, and culture.”

“In so many ways, the American experience is the African American experience,” said Lonnie Bunch III, director, NMAAHC, in his 2014 article, “America’s Moral Debt to African Americans.”

“In every development of our country’s history, every step that has made America better is tied to African American lives, patriotism and sacrifice.”

Sadly, too many U.S. and global citizens are still not aware—through hundreds of years of misinformation campaigns, propaganda, outright lies, and personal indifference—that this country was literally predominantly built by a people who were forced from their homes, beaten, starved and chained, dragged to another continent halfway across the world, and stripped of their names, their rights, their liberties, their religion, and their humanity.

“Indeed, profits from slavery provided a reservoir of capital that allowed America to grow into a world power,” Bunch continues in the article. “The image of America as a just society is stained by the lack of moral reparations and fair treatment for a group of its earliest … laborers and residents.”

“America was quite literally built on the backs of Africans,” said Sir David Adjaye, OBE, and celebrated designer of the NMAAHC, in an interview with Charles Henry Rowell, for the Callaloo journal. “Its culture is fundamentally imbued with an African sensibility. America cannot be fully understood without this conceptual lens.”

Interestingly, according to a 2016 article by Kelly Crow in the Wall Street Journal (Online), “The museum can trace its roots to 1914 when “black” Civil War veterans first asked Congress to build a museum to chronicle the saga of African Americans.”

These brave soldiers were attempting to be recognized, nationally and deservedly, for their valiant efforts in fighting for the freedoms of all Americans.

Unfortunately, the putrid and unjust acts of racism practiced by many of the country’s leaders, at that time, kept those veterans’ dreams from coming true. However, similar to the experience of African Americans and the mythical Phoenix, their objective rose from the ashes of hatred and came to fruition, triumphantly, in 2016.

The nearly 60 area travellers who enthusiastically took the South Jersey Holocaust Coaliton’s offer to visit the museum, were happy to be there and eager to explore the museum’s contents.

“This is [one] place I’ve wanted to come for quite some time, my mother too,” said Salita Demary, public relations practitioner. “So, we decided to make it a girl’s day out …”

“I looked into it and thought it strongly connected to many of the initiatives produced at RCSJ Cumberland Campus’ Library in recent years,” said Katherine Givens, part-time librarian at RCSJ – Cumberland. She also, “… thought it was a great opportunity to enrich my own knowledge [on African American history].”

Some of the sojourners were making a return trip to the Museum. “This is my second visit,” said Lisa Stewart Garrison, an independent consultant. “My first visit I found the museum to be so incredibly encyclopedic that I wanted to come back so I can concentrate, which I did today.”

“I wanted to come back so that I could experience the exhibitions and messages on a deeper level and with greater focus.”

The NMAAHC is chock full of exhibits and galleries filled with jaw dropping pieces that assist in narrating the African American’s story of their “Journey to Freedom.”

Some of the eye-catching pieces range from an airplane used to train the heroic Tuskegee Airmen, a bible that was once used by the indomitable Nat Turner, and a vintage boombox, which was one of the major tools of choice for those in the burgeoning Hip Hop culture of the late 1970s, early ’80s.

One exhibit left an indelible impact on several of the Museum goers.

“I was particularly affected by the Emmett Till exhibit, which showcased his story as a funeral procession,” said Desire Lara, bookkeeper for Bridgeton Public Schools Grants and Funded Programs department. “I was familiar with the case beforehand, but didn’t know the exact, gruesome details of his lynching, and didn’t know that Jet magazine featured a picture of his face after the attacks.”

“I was almost brought to tears after viewing this picture …,” she continued. “It’s a horrifying story, but one that needs to be told.”

On August 28, 1955, Till, who was 14 at the time, was heinously murdered by two men in the state of Mississippi. Till was accused by the men of whistling and/or making advances to one of their wives.

According to biography.com, “They … beat the teenager brutally, dragged him to the bank of the Tallahatchie River, shot him in the head, tied him with barbed wire to a large metal fan and shoved his mutilated body into the water.”

Till’s body was never meant to be discovered. However, with the help of an unseen hand, he was found. Till was transported back to Chicago, where he was from, and his mother made the bravest of decisions—to have an open casket at his funeral so the world could see the brutality that was done to her son.

That casket is on display at the NMAAHC. “Emmett Till’s casket was something to see,” said Demary.

To continue with Till’s story, the two men who murdered him got off scot-free after they were acquitted of all charges after a trial conducted by their peers. What may be the saddest part of this story is in 2007, according to biography.com, the woman who was allegedly whistled at by Till, “admitted (in an interview released in Vanity Fair in 2017) that she had lied about Till making advances toward her.”

One of the galleries that stuck out to Givens was the segregated railway train. “There was the ‘white only’ section in the front, which had large bathrooms with what looked like a lounge area, more spacious seats in the train, and more leg room,” she recalled.

“In the ‘colored only’ section in the rear, the bathrooms were maybe a third of the size of the ‘white only’ bathrooms, more cramped, and more tight. The accommodations were not close to equal, despite the ‘separate but equal’ doctrine confirmed by Plessy v. Ferguson decades before.”

For every exhibit and gallery that showed the trials and tribulations of the life of Americans of African descent in this country, there were more that displayed their triumphs and jubilations.

The Museum’s collection includes a button asserting that “Black is Beautiful,” headgear worn by the Greatest of All Time, Muhammad Ali, and a photograph of two elegant, melanin-toned women dancing from a production of “For Colored Girls.”

“I’m really into the arts, so seeing the costumes from Broadway and things like that, that was really awesome,” Demary declared.

“I like how [the exhibits] highlighted women,” said Demary. “I think women can be glossed over, so that really struck a chord with me that they highlighted [African American] women and their roles and the things that they went through.

The Museum is helping to clear up hundreds of years of distorted messages that have been—and still are being—presented as truth about the African American experience, mostly via media and our educational system.

“I think there’s some truth in what’s been taught in the history books, but a lot of historical detail has also been excluded in schools and mass media to fit a narrative,” said Givens. “I believe a lot of people want to be blameless or lessen their culpability, so the historical narrative is bent and molded to soothe their conscience.”

“I honestly didn’t know that most slaves were captured and shipped form primarily the West African coast,” said Lara. “And that African royalty, during this time, allowed some of this slave trade to take place, in order to avoid total war and conflict [with Europeans], and to continue the new success of international trade.

“This was certainly not taught to me while I was in school. When I was in high school, we had one African American history class, which was an elective. One. Crazy.”

Stewart Garrison had another take on this topic.

“I’d say it’s a major work in progress,” she said. “But I think for this to be an endorsed message emblematic of our national story told within the framework of how we tell stories in this country is a huge breakthrough.

“It’s a cultural moment that I feel very privileged to be alive for…”

The area residents who travelled to the National Museum of African American History and Culture were able to learn—and relearn—many valuable lessons about a people whose true history is beginning to come to light.

For more information about the National Museum of African American History and Culture, visit nmaahc.si.edu