Hang Gliding

The flying squirrel’s parachute-like body enables it to glide from heights to lower elevations in a way that humans have tried to emulate.

Mid-March, while leading a nature hike, I had the urge to walk up to a hollow tree and tap on it to see if anything interesting might transpire. I was trying to peer into a hole when a saucer-eyed face came within about four inches of my nose. I chuckled and turned to my fellow walkers, with an ear-to-ear grin, exclaiming, “That was a flying squirrel!” Some responded that they had seen it but hadn’t known what it was. So I knocked again and this time the squirrel scrambled out of the hole. He perched momentarily on top of the hole’s ridge, where a limb had once projected when the tree was alive. Then he ran to the back side of the tree. Now everyone was equally amused—well, I suppose not the squirrel, who I likely disturbed from a mid-day slumber.

This encounter caused me to reminisce about a number of interactions I’ve had with these gliding mammals.

On occasion, Natural Lands Regional Director Steve Eisenhauer has removed a lid from a nesting box provided for these tiny rodents, so that students can catch a glimpse of one. On one such occurence I recall that the awakened creature ran down a tree, up an onlooker’s legs, then leaped onto a neighboring tree. It all happened so fast that there was no time to be anything but surprised and amused.

We seldom see flying squirrels because they are nocturnal. However, in suitable habitat, for example where a birdfeeder is lit by a spotlight, some people may catch them coming regularly for snacks.

Dr. Dale Schweitzer, noted lepidopterologist (an expert in moths and butterflies), once told me that flying squirrels were attracted to his moth baits, so he saw them often when checking his sampling traps. He noted that they are much more numerous than people suspect.

My own encounters have been sporadic at best. While I was leading a walk at the Nature Conservancy’s Maurice River Bluffs Preserve, a number of us were treated to one gliding from a tall tree and descending into the lower canopy. The squirrel looked like a square—gray on top and a lighter color on the bottom, with a head on one end and tail on the other!

These small mammals have an interesting adaptation that allows them, rather than flying, to glide from heights to lower elevations. Between their forelimb and hind limbs they have a thin skin or membrane covered in fur called “patagia.” Additionally, from chin to wrist and again from the hind limb’s ankle to tail, there is more skin (the uropatagium), which can also catch air in a descent.

People seeking human flight have long been envious of the squirrels’ gliding prowess. Pioneers in the field have made jumpsuits that resemble their loose skin, stretching fabric from wrist to ankle. Early attempts at human flight in such attire were dismal at best, tragic at worst. Possibly you have seen videos of modern-day base jumpers in wingsuits, leaping from cliffs. The sport seems ideal for those who value thrill over life, and these athletes reach speeds that surpass 140 miles an hour. Their apparel is continually improving, and although they have made gains in both accuracy and maneuverability it is still considered the world’s deadliest sport.

In an August 2019 National Geographic story about base jumping, it was reported that only five jumpers had died since the year’s beginning, compared to 10 during the same period the year before. In 2016 a total of 31 jumpers had succumbed. Five of those who were killed were considered the preeminent in their sport (pause for reflection, please!). Are fewer numbers of deaths indicative of improving technology? Are fewer people drawn to the activity given the risks, or is attrition caused by deadly incidents? The article left this question unanswered. I have parasailed off a cliff in Lima, Peru, but I will not be rocking in a base jumper’s squirrely suit in this lifetime!

The few flying squirrels I have seen in action appear to travel much more safely than their human kamikaze counterparts. They seem more lofty, less speedy, and considerably lighter. My first encounter with these wee creatures was about 40 years ago when I was navigating around a fallen tree. Two came out of the stump, ran the length of the trunk toward me, and froze about two feet away, so that we were essentially face to face. We exchanged a very long appraisal of each other’s intentions. Their deep brown eyes were huge in proportion to their small faces; it was an ET moment to be sure. I called to my husband, “Um, I’m looking at four eyes and I’m not sure who they belong to!” Then I thought for a moment and said, “Flying squirrels, I suppose.” I tilted my head, evaluating our stand-off, and said, “Well?” The critters scurried off.

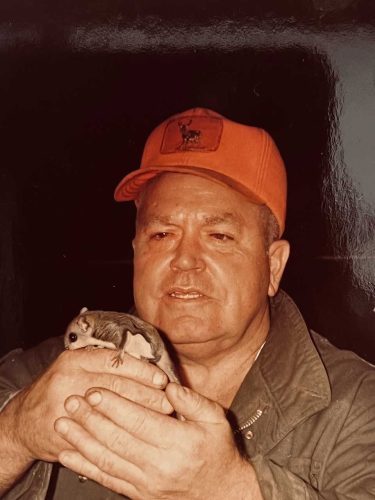

Our flying squirrels seem to have an endearing magic. About a year ago I wrote about Berwyn Kirby who passed away in 2020 at 84 years of age. I spoke of his football accomplishments at Penn State, his brawn, and the gruff persona he projected. He was also reduced to a pussycat when it came to his true love, his wife Kay.

Berwyn was known as the Menantico Troll, yet he befriended a tiny flying squirrel who he dubbed “Roscoe.” The loveable little rodent made regular trips up the brick wall of their fireplace mantel for food and drink, provided by a fellow who would hardly allow a soul near his property, let alone in the house! This irony escaped neither of us. I laughed openly at the bizarre nature of their relationship—a burly guy and his tiny friend.

I teased Berwyn and suggested that the friendship would end in trouble, to which he replied, “But he’s really a little character; he’s so cute.” Eventually, after Roscoe tried to take over the house, the true boss gave him an eviction notice. We both knew it would come to this as so many ill-fated relationships do.

Wild animals are just that—wild—and best left in the great out-of-doors.

Sources

Smithsonian Science Education Center

National Wildlife Federation, Educational Resources

PBS Nature

Squirrelgazer.com

Animal diversity website

Purdue University College of Agriculture

Flying Squirrel Facts

- Two flying squirrels are native to North America:

- Northern Glaucomys sabrinus: 10–12 inches long

- Southern Glaucomys volans: 8–10 inches

- They are chipmunk-sized.

- Preferred habitats are wooded areas with dead and rotting trees. Woodpecker holes provide housing.

- Breed two times a year: February through March with young born March to mid-April, and May through July with young born July to August.

- Care of young: female only.

- One to seven kits in a litter.

- Weaning in five to eight weeks

- Female fertile for first three years only.

- Lifespan three to five years in wild

- Both are native to New Jersey, however the Northern is rare around homes and prefers high peaks and spruce/fir forests. In our area we are more apt to see the Southern type.

- There are a number of large flying squirrels on earth. One of the largest is the red and white giant flying squirrel whose body measures up to two feet long.

- Nocturnal, so is seldom seen.

- They are social and live in groups.

- They communicate with ultrasonic vocalizations but also make squeaky sounds that can be heard.

- They can leap many times their own body length, as long as 300 feet! They can also turn 180 degrees in mid-air.

- Omnivores. preferred food is fungi. They also eat insects, birds’ eggs, carrion, berries, hickory nuts, acorns, and other seeds.

- Their limbs are longer than that of other squirrels in order to stretch the patagia, making their parachute as large as possible.

- Upturned tips at their wrists give them the ability to steer and achieve stability. Many of today’s airplanes use the same design.

- They can attain speeds up to 20 mph.

- They are hunted by snakes, raccoons, owls, bobcats, and house cats (keep cats indoors!)