Glass Industry

Whitall Tatum & Co.’s South Millville plant and Glasstown factory played key roles.

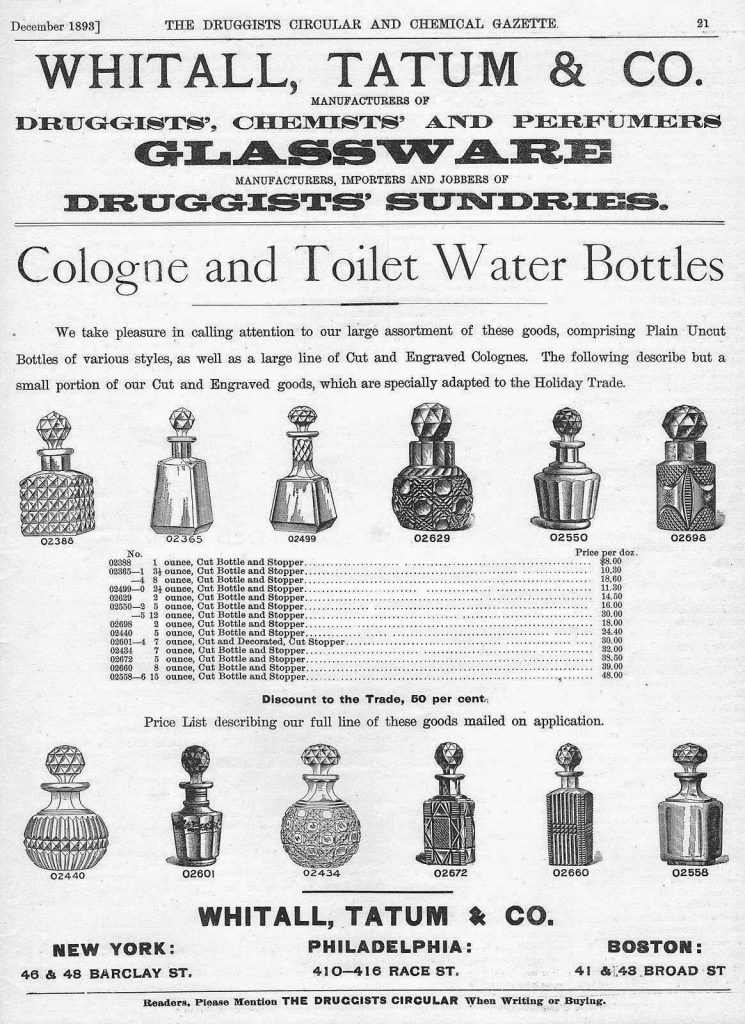

The success of Millville glass manufacturer Whitall Tatum & Co. in the second half of the 19th century was the result of the vision of its owners and accomplished glassblowers.

John M. Whitall, whose involvement in 1838 commenced 100 years in which his family’s name was involved with the company, helmed the Philadelphia office, preferring to run things from the City of Brotherly Love despite being a South Jersey native. He had purchased for his family a home at 1317 Filbert Street in Philadelphia, which gave him a convenient proximity to his workplace.

It wasn’t long, however, before Whitall surrendered to the lure of his home state. He purchased a summer home in Atlantic City in 1856, enjoying seasonal visits to the shore each year.

By 1852, the firm chose to expand, adding an office in New York City at 96 Beekman Street, according to Virgil S. Johnson’s book Millville Glass: The Early Days. In 1868, the New York division relocated to 7 College Place, where it remained until 1875 when a move to 46 Barclay Street began a 53-year residence in that particular location.

Johnson’s book contains an interview with glass-industry veteran William Pedrick II, who began his career at Whitall Tatum as an office boy. According to him, by the start of the 20th century, the New York office had 42 salesmen on the road.

The company had also opened a Baltimore office in 1869, but by that time, it had been five years since Whitall had left the firm. Along with his departure in 1864, he purchased a farm in Haddon Township as a second summer home the family could enjoy. When he died June 6, 1877, it was in his native state in Atlantic City.

Whitall Tatum & Co. continued to thrive after Whitall’s departure. According to the South Jersey Magazine series “Millville’s First Glasshouse,” the company began manufacturing plate ware in 1868, homeopathic vials and lamp ware in 1873 and chemical ware in 1878.

In 1881, two significant developments occurred. The Schetterville plant, a second factory acquired by the company to augment its Glasstown operation, was rechristened the South Millville factory and a railroad line was added in close proximity to the plant, facilitating a quicker flow of products.

According to Johnson’s book, “the first shipping [of Whitall Tatum glassware], was done by water, both raw materials and finished goods being moved in this way. The company owned two sloops, two schooners and a steamboat.” These vessels, named Ann, Franklin, Caroline, Mary and Millville, transported products in boxes or barrels lined with hay or straw to Philadelphia, Baltimore and New York, returning with supplies from those locations.

Johnson explains that “early shipping was done by teams [of workers]. Even after the railroad came to Millville in 1863 [sic], the ware was carted to the depot by the team. Incoming freight was handled in the same way. In 1881 there were twelve teams at Glasstown and eighteen at South Millville.”

Before the end of the 1880s, according to South Jersey Magazine, the company “put tract scales, locomotive and railroad tracks to the furnaces in [the] South Millville yard.” Johnson notes that the addition meant that “incoming and outgoing freight [was] handled direct” and that “boats were gradually abandoned for the more modern way of handling, and the teams finally gave way to trucks, tractors and electric trucks.”

In 1890, two furnaces were added to the South Millville plant, bringing the total to 12. The decade was spent replacing, repairing and upgrading equipment at both facilities and adapting to the changes that had been introduced to the glass manufacturing world.

As the 20th century approached, the company’s employees had grown to nearly 3,000, a number that would climb higher once the new century arrived. According to Pedrick’s account in Johnson’s book, the first decade of the 1900s witnessed 2,400 workers in the company’s South Millville plant and 1,400 in its Glasstown factory.

Whitall Tatum & Co. was incorporated on January 2, 1901, “the old firm being dissolved by mutual consent,” Johnson writes. “All its assets were turned over to the new company which was to assume all of the liabilities of the old firm.”

Next Week: Tending Boys