Genius Design

Vineland’s founder was ahead of his time in planning urban spaces.

Vineland’s distant connection to Philadelphia’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway, which cuts across the grid from City Hall to Fairmont Park, may be well over a century old but with the current plans to re-imagine the famous roadway, a different perspective of that relationship has unfolded.

Vineland’s distant connection to Philadelphia’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway, which cuts across the grid from City Hall to Fairmont Park, may be well over a century old but with the current plans to re-imagine the famous roadway, a different perspective of that relationship has unfolded.

In March, the WHYY website reported that “Philadelphia is moving forward on a long-term plan to overhaul much of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway with an eye toward improving access for people walking and biking.” The plans date back to 1999, according to an article earlier this month by Inga Saffron, architecture critic for the Philadelphia Inquirer, with an eye toward “bringing more daily activity to the Parkway and making it less hostile to pedestrians.”

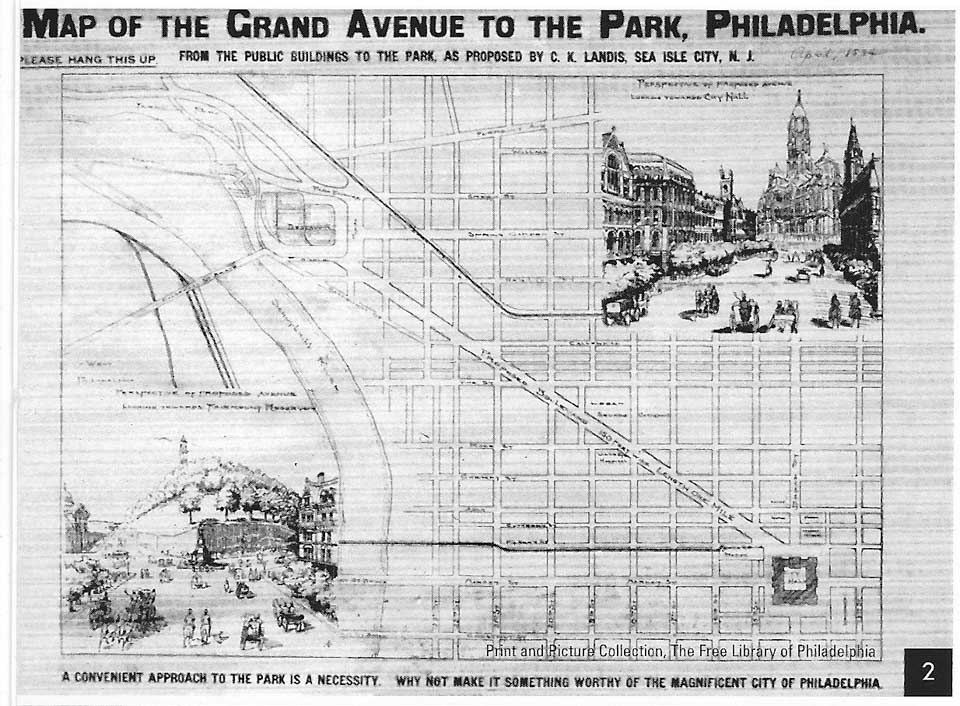

In the final year of the 20th century, the design for the roadway by Jacques Greber was 82 years old, having “borrowed heavily from triumphalist avenues like the Champs-Élysées,” WHYY notes. Philadelphians tend to trace the Parkway’s origins to Greber. Vinelanders prefer to examine what occurred some 30 earlier when Vineland founder Charles K. Landis offered what can be considered the first serious attempt at a Parkway design for the City of Brotherly Love.

That design, completed in the mid-1880s and pitched to a disinterested Philadelphia political system, bears an uncanny resemblance to the current Parkway, save for several distinctions that can’t help but be examined in light of the criticisms aimed at the existing avenue.

WHYY notes that “with demand for public outdoor space only growing and new attractions coming to the area, city officials are now focused on a coherent plan that can help the boulevard transcend the autocentric and fragmented identity forged over the course of the last 100 years.” It also explains that “pedestrian access between the Parkway to the iconic Art Museum…was for years largely routed into a single crosswalk that required those on foot to cross six traffic lanes and two bike lanes.”

WHYY notes that “with demand for public outdoor space only growing and new attractions coming to the area, city officials are now focused on a coherent plan that can help the boulevard transcend the autocentric and fragmented identity forged over the course of the last 100 years.” It also explains that “pedestrian access between the Parkway to the iconic Art Museum…was for years largely routed into a single crosswalk that required those on foot to cross six traffic lanes and two bike lanes.”

Greber’s design couldn’t help but cater to the autocentric. Mass production of automobiles had begun in 1900 and predicted the future of travel. When Landis began to promote his design in the late 1880s, cars were only being produced in limited capacity in Germany. His vision, therefore, was one of leisure rather than speed.

Landis had a map of his parkway design circulated throughout Philadelphia with one of the corners depicting a view approaching Fairmont Park and another approaching City Hall. In each, a wide avenue is filled with horse-drawn vehicles and individual riders on horseback. There are no lanes. And there is no apparent hurry.

It’s worth noting that Landis had been seemingly inspired by Philadelphia’s 1871 parkway proposal, the first following the city’s recommendation for urban renewal in 1858. Roger W. Moss, in Historic Landmarks of Philadelphia, reports that “a proposal dating from 1871 argued that if the park was truly to benefit the people of Philadelphia, it ‘must be brought within reach of all. It must be connected with Broad Street and with the centre of the city by as short a route as possible; and the avenues which lead to it must be made elegant and attractive.’ ”

It’s not surprising, then, that Landis’ plan addressed all three points, as his map demonstrates. Cutting across the grid connected Center City with the park “by as short a route as possible.” And he knew just what to do to make the route “elegant and attractive.” His map’s illustrations contain a tree-lined roadway with plenty of foliage, much like Vineland’s at the time.

When it comes to what Philadelphia desires from its current re-imagining of the Parkway, it might be pointed out that Landis’ design already had those features which, with appropriate observance and embellishment over the next century, would have adapted to changes over time. It’s also interesting to note that Landis hasn’t been mentioned at all in recent articles about the Parkway.