Feathers of a Turkey

Most of us won’t see our bird with plumage attached—we can only imagine.

For the Thanksgiving holiday it is once again time for me to unleash more gobbledygook on the readers. As it turns out I’m really into turkeys and love to tell turkey tales. Our focus is on the different plumages characteristic of subspecies, plus the impact of recessive genes. And a little travel storytelling for good measure.

For the Thanksgiving holiday it is once again time for me to unleash more gobbledygook on the readers. As it turns out I’m really into turkeys and love to tell turkey tales. Our focus is on the different plumages characteristic of subspecies, plus the impact of recessive genes. And a little travel storytelling for good measure.

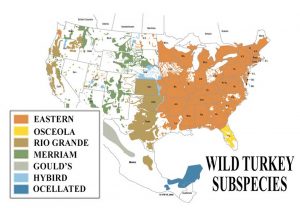

There are five subspecies of wild turkeys here in the United States. The bird we see in our region is called the Eastern wild turkey. It has the lovely chestnut brown and tan coloring accented by iridescence that in the sun can provide lots of lovely shades of navy, gold, and copper.

This is the most common turkey, with populations in 38 states, and they have the longest beards of the various subspecies. Females can also grow beards when they have the recessive gene for this trait, but it occurs in only 10 to 15 percent of females and they are rarely as robust as toms.

All five subspecies of gobblers in the United States—Eastern, Osceola, Rio Grande, Merriam’s, and Gould’s—weigh 18 to 30 pounds, with hens eight to 12 pounds, although the Osceola or Florida male turkeys grow no larger than about 20 pounds.

It is the plumage that differentiates the subspecies from each other. Hunters who bag four types, absent the Gould’s are considered to have achieved the Grand Slam of turkey hunting. Including the Gould’s it is a Royal Slam. While the Gould’s wild turkey is primarily a resident of Mexico, there is a small population in Arizona. They are the largest of the subspecies.

Ten years ago we hunted on Ted Turner’s 550,000-acre Vermejo Park Ranch, which spans portions of northern New Mexico and southern Colorado. More than two-thirds the size of Rhode Island and a bit larger than the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, it’s an impressive spread. There my husband and I were introduced to Merriam’s turkeys. Their bodies look very much like the Eastern birds, but their rump feathers are nearly white in comparison. The final band of color on the fanned tail is a buff to white color and broader than the Eastern bird’s tail band. When the Merriam’s gobbler displays, the band creates a very bright halo effect.

Ten years ago we hunted on Ted Turner’s 550,000-acre Vermejo Park Ranch, which spans portions of northern New Mexico and southern Colorado. More than two-thirds the size of Rhode Island and a bit larger than the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, it’s an impressive spread. There my husband and I were introduced to Merriam’s turkeys. Their bodies look very much like the Eastern birds, but their rump feathers are nearly white in comparison. The final band of color on the fanned tail is a buff to white color and broader than the Eastern bird’s tail band. When the Merriam’s gobbler displays, the band creates a very bright halo effect.

In contrast to the Merriam’s, our Eastern turkey’s outer band of color is thinner and coppery in color. And the rump feathers leading up to the Eastern’s tail are longer, appearing chestnut with seemingly pink hues. Merriam’s are considered lanky and are known to be better climbers than the Eastern variety.

On these hunting excursions we always add natural and cultural investigations to our agenda. At Vermejo we spent some time talking with people who were studying the natural history of the large Gunnison prairie dog colony that is present on the ranch. This species has suffered range-wide declines from an exotic disease, sylvatic plague. Since fleas are the vector for the plague, dusting burrows to kill them was one approach used. Recently they have been testing baits that contain a vaccine against the virus, and another that has an additive of fipronil, an insecticide used on household pets that kills the flea.

Habitat loss and human persecution (both shooting and poisoning) have also affected the species. Trying to navigate nature’s balances when humans impact animal populations is always a challenge for wildlife biologists. Prairie dogs are a keystone species in their habitat, and their losses impact other creatures in the ecosystem. By way of example, colonies of Gunnisons must be large enough to provide meals for their predator, the black-footed ferret, which is an endangered species. Furthermore, many prairie animals such as owls, weasels, snakes, salamanders, foxes, and various insects make use of their abandoned burrows for dens or simply to escape the desert heat.

My fondest memory of Vermejo Park was of a very steep cliff with a narrow path that ran the length of the escarpment, for what I would estimate to be a few miles. Walking in a long row along it was a large group of bull elks, with racks easily four to six feet across. They were perched high above the desert floor in a death-defying conga line. Their majesty as they essentially tightrope-walked the cliff’s face was breathtaking.

Eleven years ago we went to the Chaparrosa Ranch in Texas, where we sought the Rio Grande subspecies of turkey. This ranch is 70,000 acres, a little less than twice the size of Vineland which is 44,160 acres. Vineland ranks #1 in New Jersey cities in land area. It was difficult to get one’s head around the vastness of these western properties. Without a guide we would have been hard put to find our way around.

We went to the ranch via San Antonio and took the time to visit the Alamo, the 18th century Franciscan mission that is famous as a site of historic resistance. About 200 stalwart Texans held off a siege by Mexican dictator Santa Anna for 13 days in the winter of 1836 before the Mexican force of thousands overpowered them. This defeat rallied the Texans in their war for independence from Mexico.

Experiencing the differences at other locales across the country is interesting and sometimes scary. I’ll never forget Chaparrosa’s clay roads that transformed, after an evening of rain, from a red dusty surface into slick horror. This was not a component of temperature but of the composition of the soil beneath us. Our guide’s pickup did a 180-about-face on the slippery surface. The clay packed itself into the truck’s wheel-wells like wet snow and had to be dug out. When the weather cleared and the roads dried up a bit we were thankfully able to proceed.

I have viewed Osceolas, the last of our subspecies, strutting about in Florida when we were on birding expeditions. Their tails are very dark with a very small outer stripe. Their rump feathers are dark chocolate and their body appearance is very black with thin white bands. The Wild Turkey Federation considers them the hardest bird for a hunter to call in. Their range is limited to southern Florida.

By far the most spectacular of turkey plumages is the Ocellated turkey, which we saw on a photo safari in Belize, in Gallon Jug. The Ocellated is not a subspecies but rather one of only two wild turkey species in the world (the other being the compilation of subspecies already mentioned). It is truly a rainbow of radiant colors; feather groupings begin with scapulars of teal with orange tips, then come long subscapulars of polished copper, and white flight feathers hang beneath. Its back and rump feathers are copper and bright blue. Most striking are its head, neck, and snood, which have bright orange warts on a featherless pale blue skin. Warts are a harsh name for what often looks like pearls decorating the head. The snood, or the fleshly protuberance above a turkey’s beak, can stick up like a horn or dangle down past its bill, in the same manner as our native American subspecies. This bird’s range is restricted to the Yucatan Peninsula. Ocellated toms reach 11 to 12 pounds and hens six to seven pounds, making it a very large gamebird but much smaller than their American cousins.

At Gallon Jug we stayed at Chan Chich in a cottage with wooden slatted blinds for windows. Each morning the Ocellated turkeys woke us with their nasal grunts and puts, plus sounds like a soft domestic goose’s honk.

Locally you may have noticed some of our wild Eastern turkeys looking very different from the rest of the flock. About one percent of turkey are what is called smoke, or smokey gray phase or morph. These birds can vary quite a bit, with some looking like a checkering of black and white and others looking tawny and white. Primarily they lack the dark brown pigments, and this is caused by a recessive gene. One is in our neighborhood currently and she’s a real beauty.

Melanistic birds also exist. They have extra melanin in their pigment, associated with black coloring, and display nearly black plumage. This year the lower Maurice River had an osprey that was believed to have this characteristic as it appeared primarily black. At first the coloration was suspected to be caused by an oil spill, but our local ornithologist finally concluded it was in fact due to melanism.

There are also leucistic birds, which can appear in all species. This is rare and occurs in mammals such as deer as well, with animals appearing especially pale or white in color. They are not albinos since their eyes are not pink. Leucism is the absence of pigment cells in the skin where albinism is the reduction in melanin containing pigment in all tissues. Piebald patterns occur when only some cells lack the pigments and a blotchy effect of white is the result. By the way, the Cape May County Zoo has leucistic deer and provides informative panels that describe these differences.

I think it is safe to say that most readers will never see the plumage of the bird they consume this week. Most farm-raised birds are white-feathered and generally are never pardoned. Happy Thanksgiving!

Sources:

National Wild Turkey Federation

Turner Biodiversity

Washington State University, Washington State Magazine

National Audubon