Eyes on Eagles

On January 19, an adult eagle revealed that three eggs had been laid in its Duke Farm nest. Eagle cameras around the world offer new insights into nature’s activities. Note the scrape the eagle makes for its eggs. Photo: snapped from live eagle cam

Eagle cams give us a closeup and personal view of an iconic bird. Read on to see how to view for yourself!

She lies still but ever vigilant. Occasionally she shifts her body from side to side or raises up to reposition herself, only to once again lie quietly over her selected spot. Beneath her is the scrape or depression she has crafted to hold her precious progeny, in one of nature’s most perfectly engineered feats—an egg. On this day, January 18, a third egg was added to the two already laid. Snowflakes fell steadily on her back. These melted, turned to water droplets, and rolled off her waterproof feathers onto the nest below.

She is brooding her eggs in a stately sycamore some 80 feet above the ground, on the property called Duke Farms in the central New Jersey town of Hillsborough. Her nest is nearly six feet across. Her mate will likely relieve her of her duties about every four hours, but the incubation duties are primarily hers. Her stately white head and tail, charcoal back, and huge yellow beak are as iconic as are her ties to our nation: She is indeed an American bald eagle.

Her fortitude and dedication are apt symbols of our national ethos, and simply the sight of her majesty can bring a teary eye to the most hardened of hearts. But watching her brave the elements in order to see her species perpetuate raises my admiration to even greater heights.

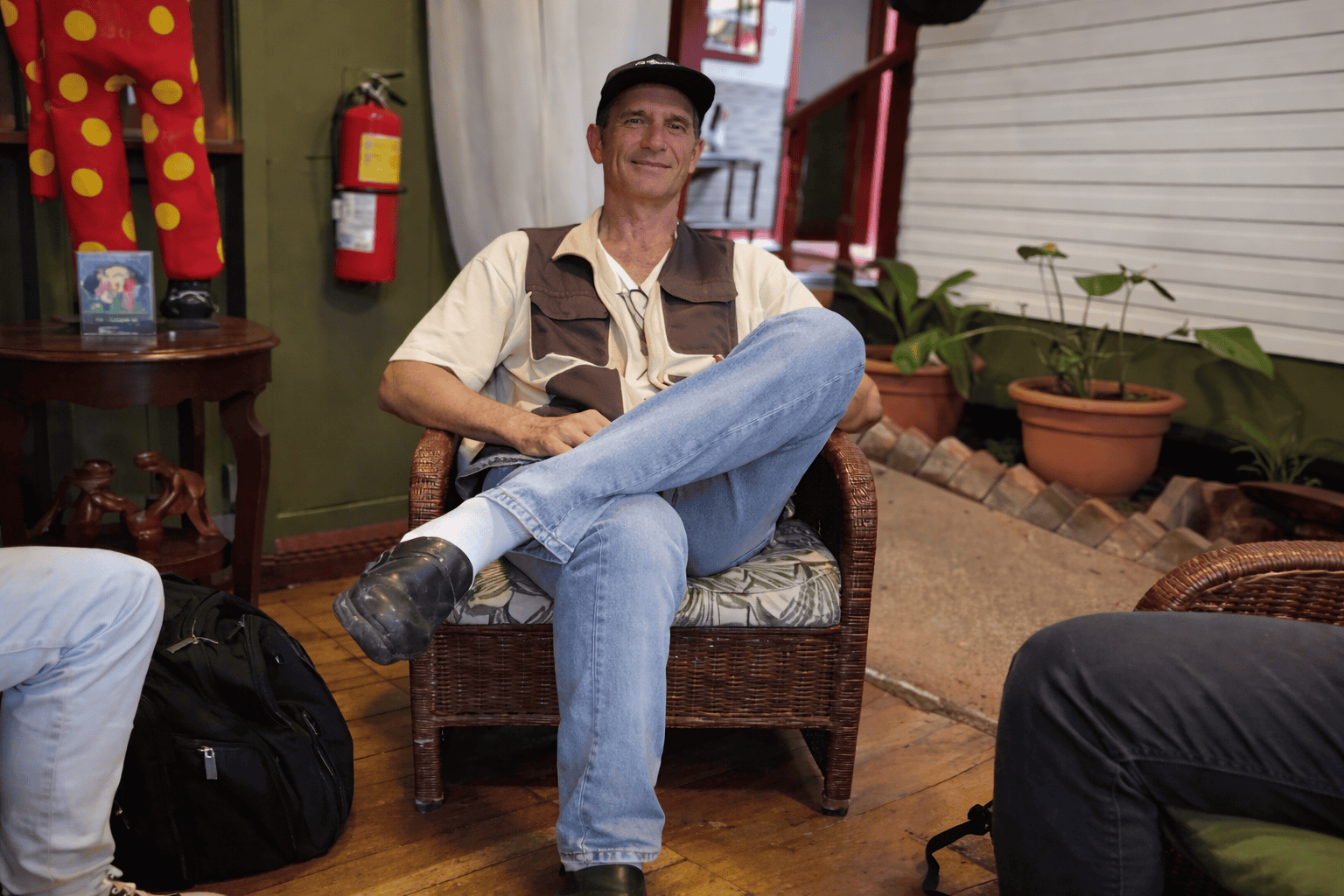

This great bird of prey is subject to a wider audience about which she neither knows nor cares. She, like some other animals around the country, has a nest cam, a camera that folks can tune into, via WiiI, to take in the live action. On this snowy day I wanted to learn more about how eagles brave the elements. So, like so many people before me, I became a voyeur—or as I/we would prefer to be known, a “citizen scientist.”

Wildlife cameras throughout the world have enabled biologists to witness behaviors and log data that was not possible prior to current technology. And it has allowed people like ourselves to broaden our knowledge and appreciation of nature. Because birds’ nests are static, these locations offer prime wildlife watching opportunities.

In 2018 the Hanover, Pennsylvania bald eagle cam documented eagles Liberty and Freedom allowing the snow to act as further insulation to their chicks. Photo: Pennsylvania Game Commission of Wildlife Cam

Let’s explore how eagles manage the raising of chicks in brutal conditions. As you may have guessed, she and her mate are especially equipped for the task at hand. Before laying eggs and during incubation, a patch of skin loses its feathers beneath the neck and on the belly of the male and female—an area called a brood patch. This allows the warm surface blood vessels in the skin to have direct contact with the eggs, permitting greater heat transfer to the unhatched offspring. Additionally the adults must turn the eggs, so that the heat is evenly distributed to their surfaces. Sometimes they stand up and move the eggs with their beak and feet; also the parent birds’ wiggling into place helps to rotate the eggs and position the remaining feathers to achieve greater contact with the exposed skin.

Heat is further achieved by the eagle’s body temperature, which is 104 to 106 degrees compared to our 98.6.

Their greatest defense against cold is the insulation that their 7,000-plus feathers provide. A raptor’s (bird of prey) outer feathers are stiff and waterproof, blocking wind and rain. These heavier feathers are layered like shingles, shedding water away from the body. Birds also spread preening oil from a gland near their tail to keep their feathers waterproof. (Most species of birds have preening glands; some exceptions are cassowaries, rheas, kiwis, and bustards.)

By design birds’ feathers are moisture-resistant, each having a main shaft or rachis that has branches called barbs and barbules with hooklets; all of these components interlock to keep the bird’s feathers water-repellent. The stiffer feathers provide a type of armoring to the light fluffier feathers beneath. The downy lower coat of feathers traps pockets of air near the body, which warms the air and creates insulation. In fact, people’s down-filled jackets and quilts, with their outer protective shell, were conceived of through human observation of birds’ coping mechanisms.

Birds, however, have a trick that our jackets lack; they can puff up their plumes (ptiloerection) to trap more warm air between the outer coat and the down. When they fluff themselves up and give a shake this is called “rousing of the feathers,” or simply rousing. This helps align the plumage and tidy it up, similar to a dog’s shake. It also rids the feathers of water, dander, and dirt. Birds augment this behavior with preening, or realigning the components of each feather’s anatomy with their beak so it will perform the tasks needed for flight and protection from the elements.

Piloerection can serve the additional purpose of creating the appearance of a more imposing adversary as a means of self-defense, or simply as a display of aggression. Thus the expression, “Don’t ruffle my feathers.”

As I watched the live-streaming camera the snow began to accumulate on the nest, and as the evening progressed three to four inches surrounded the incubating eagle. I wondered how high the bird might allow the snow to mount in its eyrie. I discovered that it is not unusual for eagles to have only their heads above the snow while they use it as a blanket for insulation. The snowfall at Duke Farms on the 18th was not deep enough for me to witness a buried eagle, but I found photos from other cams that were very impressive, where only the head of the incubating adult was visible above the snow.

A common question is how birds keep their legs and feet warm in winter. The arteries and veins in an eagle’s legs lie close together to help both newly pumped and returning blood to maintain a higher temperature—or counter-current heat exchange. “Bird legs and feet also have little soft tissue, so they don’t require as much warm blood flow. When they need a quick warm up, they can tuck one foot up against their body, underneath all those warm down feathers—a great way to warm up the toes.” (Steward of the Upper Mississippi River Refuge website.)

Speaking of toes, eagles have talons and these are of critical importance in hunting. But talons are also a weapon preventing them from being a “sitting duck.” One of the most famous sections of footage taken by a wildlife cam is that of a red-tailed hawk who mistakenly thought an incubating eagle was vulnerable. The recording shows an eagle watching something off camera flying above it. The movement of its head allows you to realize that it is being circled by something in flight. Then a red-tailed hawk swoops in for an attack and the eagle flips onto its back and takes out the hawk with the great force of its clutching talons. It then proceeds to pluck it in a business-like way, as if to say, “Just in case anyone had similar ideas, you’re not messing with me or my chicks.” Afterwards the eagle even shakes its head, like a victorious lion.

Eagles are not only formidable adversaries; they are also excellent protectors of their nests and are beautifully designed for the task at hand. Since 2005 they have fledged 35 chicks from the Duke Farms nest, a testimony to their capability and diligence.

About Duke Farms

Duke Farms’ 2,700 acres, offering 18 miles of trails for walking and bicycling, is run by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. It is a center for environmental stewardship that attempts to restore nature, demonstrate equitable climate solutions, and engage leaders and the public in those efforts, seeking to demonstrate a nature-positive and carbon-negative future.

State biologists supervise the banding of the Duke Farm chicks on April 10, 2025. This huge sycamore supports the eagle nest and camera. Note the size of the nest compared to the people in the tree lowering the chicks for banding.

Photo: Diane Cook

The estate was established by James Buchanan Duke, an entrepreneur and philanthropist. He amassed his fortune in the tobacco and hydroelectric industry, and is the well-known patron of Duke University. His daughter Doris Duke inherited the estate and began purchasing and restoring adjacent farms. She died in 1992 yet her vision for this property, as well as a property in Hawaii and one in Rhode Island, is that it be used for educational and mission-advancing programs.

The New Jersey farm consists of 1,100 acres of grasslands and agricultural lands, 950 acres of woodlands, 400 acres of floodplain habitat, and 10 lakes that provide 72 acres of open water; the undefined acreage is in part buildings, parking, and roads. This property is an oasis for wildlife in a highly developed region of New Jersey. The Foundation has identified 247 species of birds, 523 species of plants, and boasts 14 years of public access.

To read more about Duke Farms and its founder and their achievements, check out their website at dukefarms.org.

Although you are not permitted to approach the eagle’s nest from the ground, you can observe it closely online.

The Eagle’s Nest Cam

The first nest at Duke Farms was discovered in 2004. In October 2012, Super Hurricane Sandy’s 70+ mile per hour winds tore off the upper part of the nest tree. The nesting pair built a new nest 100 feet from the original location in December of the same year. In June 2023, portions of the nest collapsed (not uncommon). The eagles persist at Duke Farms, and since 2005, 35 chicks have fledged from the nest.

Eagles are one of the earliest nesters and begin laying eggs typically in mid-January to mid-February. Eggs generally hatch in five weeks and chicks fledge in 10 to 12 weeks.

The first nest cam was installed in March 2008, and in 2013 the camera was moved to the new location. In 2015, after the eaglets fledged, that camera was struck by lightning. Before the 2016 nesting season an infrared camera was installed and currently the nest can be viewed at night.

The camera at Duke Farms is hosted by the organization. The Endangered and Nongame Species Program and Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey provide biological expertise and band the chicks.

How to watch the nest or learn more: enter “Live Bald Eagle Cam, Duke Farms” or https://conservewildlifenj.org/wildlife-cams/duke-farms-eagle-cam/