Buck Moth

Its lifecycle is a true ugly duckling to swan story.

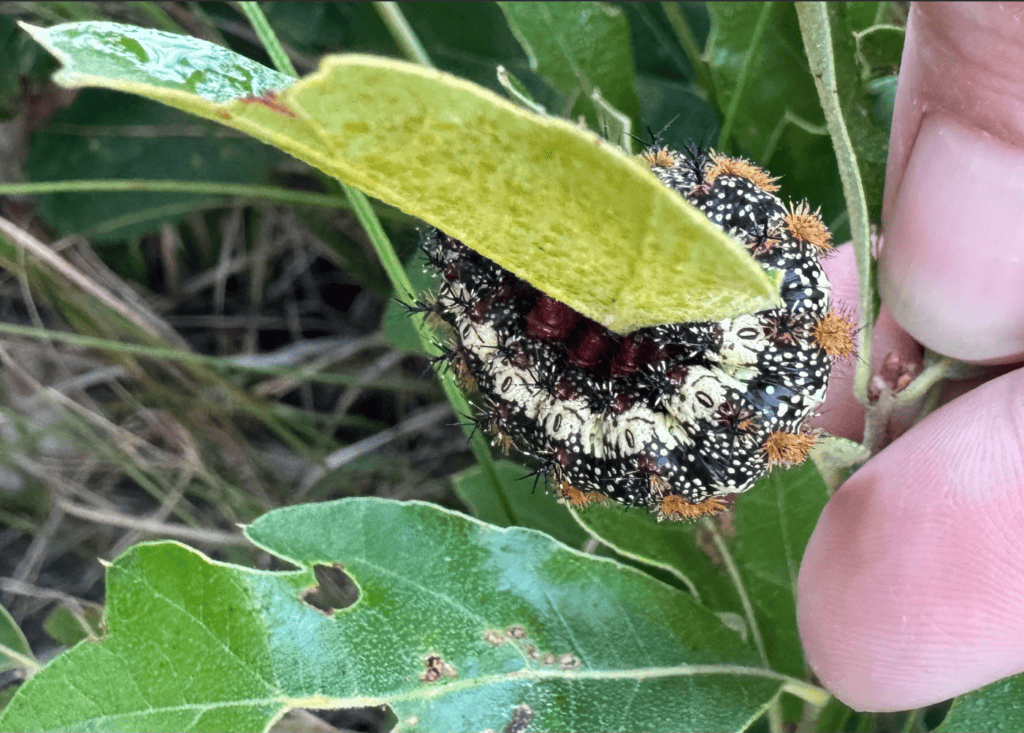

Buck moth caterpillar on white oak leaf. Note the numerous multi-branched spines, which pack a powerful venom that produces a stinging sensation. Photo: mkfierke, iNaturalist

One of our forest denizens shows up as an adult around October 20 through November 10. It gets its name from its adult sightings coinciding with the deer hunting season—the “buck moth” or Hemileuca maia (scientific name). It appropriately sports a Halloween black-and-orange coloration when it debuts as an adult in October. It’s found in oak forests from New England west to Kansas and south to northern Florida, the Gulf states, and eastern Texas.

In its larval stage it eats oak leaves—shrub oak, blackjack oak, white oak, dwarf oak. It is especially fond of live oak, an evergreen occurring along the Gulf and Atlantic coastal plain from Virginia southward. Live oak can range in size from a shrub to a massive tree with abundant acorns. Although the buck moth caterpillars will eat willow, wild cherry, and rose bushes, they have a strong preference for oak.

Recently, I came across a female flying near the ground and had to dust off my early recollections of this species. Sometimes I think my childhood eyes and all the hours spent in the woods simply made me a better spotter in my youth.

Female buck moth. Note the forewing’s black-bordered reniform (kidney-shaped) spot. Photo: J. Morton Galetto, taken October 25, 2025

In its spring caterpillar stage the buck moth gets a lot of press, especially in southern climes where live oaks are numerous and have been planted as shade trees. In that area, wandering two-inch to 2.5-inch caterpillars are noticeable on sidewalks and streetscapes, which can lead to a greater likelihood of children picking them up. On the other hand, in southern New Jersey they are much more prevalent in oak woods, where sticks and leaves and other ground cover camouflage them.

Possibly your parents told you as a child not to handle spiny or hairy caterpillars. That’s because some of them secrete a venom. The buck and io moths are two such species. In our region I have never heard of them being a nuisance; however, in the Gulf—especially in Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana, and in some areas of Virginia—caterpillars can be a significant problem for humans. In fact, the Louisiana Children’s Medical Center issues health alerts in April and May when caterpillars are most abundant.

The surface of the larva has bristly spines or hairs called setae, that get stiffer with age. The multi-branched spines form rings around the body. The setae are attached to a venom gland containing urticating fluid, and when touched they can cause a dermatological reaction. A handler can get a nasty sting—severe itching, swelling, redness, or, rarely, an allergic reaction. First aid recommendations are to remove the spines with duct tape, tweezers, or use the edge of a credit card to scrape them off (great for honeybee stingers as well), but don’t try removing the spines with a bare hand. Afterwards apply ice or a steroid cream, and take Ibuprofen for pain; take an oral antihistamine such as Benadryl if an allergic reaction occurs. Welts and discomfort can last from 24 hours to a week after contact. Severe reactions are rare but possible. One of my friends who handles caterpillars as his profession says that for him the sting normally persists only a few minutes. The best advice: Look but don’t touch!

^ For the first three instars, buck moth caterpillars are gregarious. Afterwards they disperse. Photo: Phil Myers under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

v Buck moth eggs wrapped around the twig of a live oak tree; the mourning cloak butterfly deposits its eggs similarly. Photo: Gerald J. Louisiana State University, Bugwood.org

The larvae can’t attack you. Typically the problem occurs when a child picks one up, a barefooted person steps on one, or you sit or lean against one by accident. The urticating venom is the only defense these creatures have against predators.

When abundant they can be the target of agricultural insecticides where defoliation is a concern of nurserymen, but cases seem limited. Unless a tree is stressed it will survive a defoliation and in fact regrow its leaves that season, if adequate moisture in the form of rain or irrigation is available.

Let’s review their complete lifecycle. Caterpillar abundance occurs primarily in April and May. They pupate (change to a pupa) from late April to June. Over three-fourths of pupa will remain in the pupal stage in leaf litter or a few inches beneath the ground for a year. However, 10 to 20 percent may remain subterranean for two to three years as pupa. Caterpillars dig into the soil and adult moths crawl their way out. They metamorphose into adult moths from mid-October to the first weeks of November. The adults lay their eggs around a branch of a host plant (generally oak) where they remain in egg form from January through March. Then the cycle repeats. Adults in the north may appear as early as September but as late as December in the south.

In their caterpillar stage they have six instars or molts. During the first three instars they remain grouped together but in their fourth instar they finally venture apart (Wagner 2005). The resulting lovely moth has a two- to three-inch wing span. Specimens vary but both males and females are considered to have black hindwings and forewings with a white stripe running along them. The forewing and hindwing have a black-bordered reniform (kidney-shaped) spot that touches the outer edge of the black patch. The body of the male normally has a rusty red tip and a female’s body typically has rusty red rings. Females tend to be larger than males.

Live oak, an evergreen species that is the favored food plant of the buck moth in the southern United States. This is the famous Middleton Place Plantation Live Oak, Charleston, SC, estimated to be between 900 and 1,000 years old. Photo: J. Morton Galetto

The wing spots of the hindwing are covered by the forewing when resting so that only two are visible. These spots are generally believed to mimic eyes and provide a defense mechanism of sorts. A predator may be deterred from attacking such an imposing creature or it might be startled by a wing flash. Additionally, if a false eye is struck the wing remains intact and the moth can still fly. Green darner dragonflies are a known predator species, and likely a number of birds prey upon them as well.

In the fall and early winter buck moths are seeking to reproduce. The female emits pheromone vapors that are sensed by the males’ larger and more complex antennal structures. In general males are the more active partner in seeking a female. After mating the female will lay about 45 eggs in a uniform bracelet-like cluster around an oak branch. The eggs will hatch in April when the larva will have a food source. Mourning cloaks lay a similar egg mass.

The fall is when you are most likely to encounter the adult moth searching for a mate. Pine barren forests with oaks are a good place to look, and the creature has a beauty that you won’t want to miss. One of the few moths that is out during the day, it is therefore easier to find than many other species that fly mostly at night. Buck moths are most commonly seen on warm sunny days between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. Quick flyers, adult males in the moth stage can travel an average of 30 miles per hour and can reach speeds of 60, one source suggests. So pack up your binoculars and take a hike among the oaks.

Special thanks to Dale Sweitzer for fielding the author’s many questions.

Sources

University of Wisconsin, UW Milwaukee, Field Station

Louisiana State University Ag Station – Buck Moth Caterpillar

University Medical Center New Orleans Louisiana Children’s Medical Center, ‘Tis the Season: Treating Buck Moth Caterpillar Stings, May 2018

North Carolina State Extension Service, Buck Moth Fact Sheet

University of Florida, IFAS – Featured Creatures

Caterpillars of Eastern North America: A Guide to Identification and Natural History, David Wagner.