A Tree with Sass

With leaves in varied shapes and colors, sassafras has many uses, one of which is to spice and thicken sauces.

This past fall I took my first trip to New Orleans, Louisiana (NOLA), where I attended a class at the New Orleans School of Cooking, on St. Louis Street. The motto boasts of “Fun, Food and Folklore.” In fact I think that might be the mantra of all NOLA tour guides. Chef Michael DeVidts did not disappoint in delivering on the branding, including a lot of history, culture, and of course garlic. Our lesson was typical Creole/Cajun fare—andouille gumbo, jambalaya, bread pudding, and sweet potato pralines. Yum!

Chef Michael told the usual tales about the French founding of NOLA, and the American side of town as contrasted with the French Quarter. Stories are as important as cooking in this kitchen.

I was familiar with most of the techniques until he asked, “Have any of you used filé powder?” I suppose most of us were Yankees and the 40-plus faces looked rather clueless, making me feel more comfortable owning my ignorance!

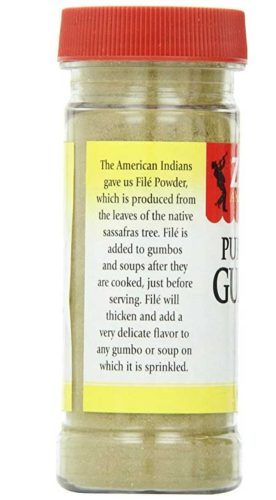

Filé (pronounced fee-lay), often sold as “ground gumbo file,” is a thickening agent used in soups, sauces, gravies, and yes, gumbo. Cooks know that cornstarch, tapioca flour, wheat flour, arrowroot powder, and okra are possible substitutes. Chef Michael had a huge pot of gumbo—I’d estimate a few gallons—to which he added maybe a third of a cup of filé, and it congealed within a few brief minutes.

I queried, “What is that stuff? I know ‘file’ but what is it?”

His answer: “Ground-up leaves of the sassafras tree.”

“Who’d of thought?” I commented.

On my forest tours I speak of sassafras having three unique leaf shapes, and in our area there are some with additional lobes. I’ve mentioned its being used for root beer and for flavoring tea, I’ve described the drupes being eaten by birds, and I’ve talked of its importance in furniture making… but never this miraculous nearly instant thickening quality! Since then I have tried it in stews and gravies and voilà, creamy thick results. I smell a difference in the aroma when I first add it, but then that dissipates and I don’t really taste it, although I’m certain you can overdo it.

I began to think about what other qualities this unassuming tree might possess. Time to dig out Daniel Moerman’s tome Native American Ethnobotany, which I decided after receiving it, should come with a sherpa to schlep it around; it’s clearly not a field-friendly pocket guide.

In it, the sassafras tree, Sassafras albidum, fills two voluminous pages with information on Native American medicinal uses, breaking each down by tribe and reference source. It further provides a plethora of ailments that I have never heard of nor do I ever wish to contract—cat, cow, racoon, and monkey sickness, otter and horse illness, and mythical wolf sickness. I’m not making this up.

I tried to figure out a modern equivalent of some of these illnesses for which sassafras bark or roots were commonly employed as treatments. Raccoons do carry roundworms and a number of tribes made anthelmintic medicine from sassafras. Iroquois made a compound of roots and whisky to treat tapeworm.

Monkey sickness stumps me as far as North America is concerned; we are not known to have indigenous primates. However some western tribes likely came in contact with Mexican and other southern tribes. On the other hand there are the otters (yes, I so wanted to say “otter hand”), clearly a North American species—their eponymous illness involves diarrhea and vomiting, although how it relates to otter I do not know. But these symptoms also were treated with sassafras.

Wolves have always been prominent symbols in Native American culture; they have been considered sacred and were associated with intelligence, strength, courage, and loyalty. Some tribes’ folklore places humans as descendants of wolves. The Tsilhqot’in tribe believed that contact with these animals could possibly cause mental illness or death. Surely rabies fits this description.

Rather than surmise further about these illnesses’ names, let’s address the reported symptoms that appear under more than one tribe’s medical usage of sassafras (especially root, root bark, bark, and oils)—diarrhea, ague, digestive health, blood purification, watery blood as well as dermatological aids for burns, wounds, cuts and bruises, and sore eyes. A number of tribes used sassafras to “increase vigor in males.”

When colonists learned of the curative powers of sassafras from the Native Americans it became an export second only to tobacco. Various teas became a fashionable beverage. It was falsely believed it was a curative for syphilis, but when its efficacy proved lacking it fell from favor and economic importance.

When colonists learned of the curative powers of sassafras from the Native Americans it became an export second only to tobacco. Various teas became a fashionable beverage. It was falsely believed it was a curative for syphilis, but when its efficacy proved lacking it fell from favor and economic importance.

Ethnobotanist Jim Meuninck summarizes sassafras’s past medicinal uses as follows: “The root decoction was used in traditional healing as drinkable tonic and blood purifier to relieve acne, syphilis, gonorrhea, arthritis, colic, menstrual pain, and upset stomach. Bark tea was used to cause sweating.”

Oils from the tree were used as an antiseptic in dentistry and for flavoring toothpastes, root beer, and chewing gum, as well as for perfumes, until the early 1960s, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced safrole, the root oil, to be a potential carcinogen.

As noted earlier filé, the tree’s dried leaves, is still used in Creole/Cajun cooking both as a spice and for thickening. In terms of wildlife, birds and bears eat the mature fruits to such an extent that they are rarely observed on the tree. Rabbits like to chew on the twigs. Other browsers include beavers, deer, groundhogs, and porcupines.

School children who learn about leaves in the fall are taught that the tree has three distinctly shaped leaves—a simple unlobed leaf (eye-shaped or ovate), a two-lobed asymmetrical leaf (mitten-shaped), and a three-lobed leaf (theropod-dinosaur shaped). However in the Maurice River watershed we see even more variety in the leaves, with additional lobes up to five.

This deciduous tree is often shrub-like in our soils. It is typically a small or medium tree 20 to 30 feet tall, but it can reach up to 50 feet in height. Rarely it may reach 80 feet with a circumference of 16 feet or more. In autumn its colors vary and it can show yellow, deep orange, scarlet, or deep purple. The twigs are smooth, yellow-green, and glossy with a large pith that has an aromatic spicy odor when crushed, often described, naturally enough, as root-beer scented. Its range can be roughly described as the eastern half of the United States extending into Canada.

One New Jersey record sassafras (1998 list) was reported at the Mt. Laurel Friends Meeting House; its circumference at the time was 17 feet, 4 inches. The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection also notes “Sassafras is believed to be the Native American name for the tree, adopted by the Spanish and French in the mid-sixteenth century.” The word albidum in its Latin name means “whitish.” Apparently the tree is surprisingly pest free, and a number of other sources mention that it repels mosquitoes and other insects.

I hope that readers enjoy the glimpses into the wonderful world of nature, both locally and farther afield, that I share. Feel free to e-mail me with comments or suggestions for other topics at forrivers@comcast.net. And please consider joining CU Maurice River at cumauriceriver.org.

Sources

Native American Ethnobotany by Daniel Moerman, 1998.

“Magic and Medicine of Plants,” Reader’s Digest, I. Dobelis, 1986.

Medical Plants of North America, by Jim Meuninck

Trees of New Jersey and the Mid-Atlantic State, NJDEP, Division of Parks and Forestry

New Jersey’s Big Trees, A list of 100 champion size trees, NJ DEP 1998