A Penny Dreadful

...with a local slant and insight on racial tensions in the region, circa 1844.

Penny Dreadfuls—cheaply made, lurid pamphlets that grabbed the public’s attention in the early 19th century—are difficult to find today. But the ones that remain sometimes provide insight into social conditions of the times. One particularly tragic tale is “The Confession of Rosan Keen,” a four-page penny dreadful printed in Philadelphia in 1844. The story was reportedly related by a 16-year-old African-American servant shortly before she was hanged in Bridgeton for the fatal poisoning of her employer, Enos Seeley, during the preceding year.

Unfortunately, even the strong Quaker influence in South Jersey at that time could not prevent African-Americans from being mistreated even if they had been born free. In her alleged confession, Rosan stated: “I was born near Penn’s Neck, in Salem County New Jersey, in the year 1828. My father was originally a slave in the state of Virginia, from whence he escaped and settled in New Jersey.”

Her father apparently lived in fear of being caught by slavers who haunted the region, eager to capture fresh prey. As a result, the Keens moved to “Millville Township” where they lived until they were sent to the poorhouse, located about one-and-a-half miles west of Bridgeton. Her father died there two years later.

When Rosan was deemed old enough to work, she became a servant in several different Bridgeton households before moving to the Seeley home in 1843. The Seeleys were a prominent local family descended from Colonel Enos Seeley, who had been a hero during the Revolutionary War. Her employer had just been appointed by Governor Daniel Haines as Clerk for Cumberland County.

The couple was apparently wealthy enough for Mrs. Seeley to own a “Gold Watch and Chain” along with other amenities. Rosan, who had never enjoyed such luxuries, coveted the watch. She reasoned that if she used poison to kill Mr. and Mrs. Seeley, she would be able to steal it along with any other money and goods she could find. Then, according to her Confession: She would “get my mother from the poor house, and then I thought we would live together.”

After her first attempt did nothing more than make the Seeleys ill, Rosan tried again using “fly poison” that she spread liberally across their evening meal one night. When they both became violently sick, she assisted the neighbors with their care, but “felt pleased with what I had done, thinking to myself I had fixed them.” She acknowledged in the Confession that she was afraid to admit her guilt for fear of being whipped.

While Mrs. Seeley eventually recovered, her husband died and suspicion fell on their servant. Seeley’s body was exhumed and after an autopsy, evidence of arsenic was discovered. Rosan, who by then had fled to Springtown, a small community outside of Greenwich, was captured soon afterward and brought to trial.

During her three weeks in jail, Rosan made several unsuccessful attempts to escape. She realized that she would soon face serious consequences for her actions.

Apparently, Rosan’s treatment was not appreciated by everyone in Cumberland County. The Bridgeton Chronicle noted that “this poor, ignorant, demented girl” was “more deserving a place in an insane asylum” than other criminals who had committed murder. But every effort to obtain a pardon for her was unsuccessful.

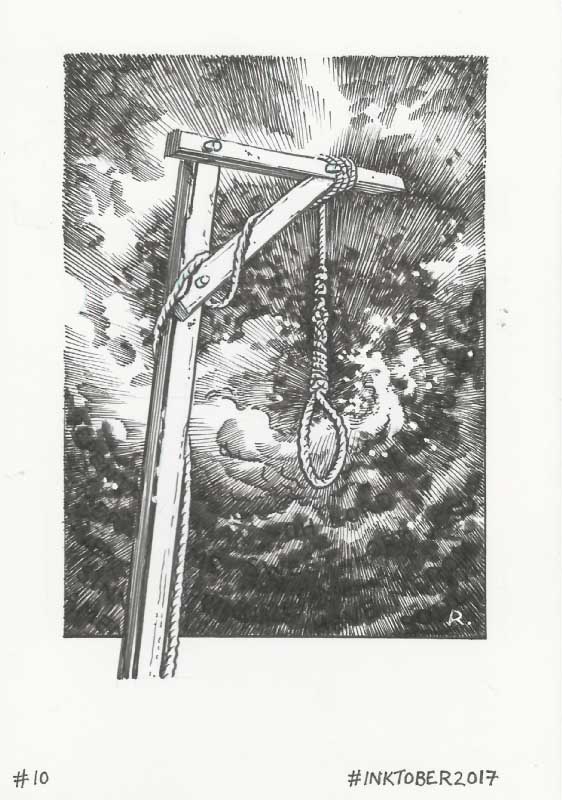

Hanged at 2 p.m. on April 26, 1844, in the jail yard in Bridgeton by Sheriff Harris Mattson, the Confession noted: “she instantly was raised up and died almost without a struggle.” After a limited number of spectators initially witnessed the hanging, “the body was not taken down until 4 p.m.” Her remains were later released to friends for burial.