A Catfish Story

There’s nothing deceptive about the catfish in our story. It’s the cat’s whiskers—its long tactile barbels—that give it the name.

We have introduced our five-year old niece to the fun of fishing by angling for channel catfish. It’s been a great deal of fun catching and preparing our harvest. You might be surprised to know that channel catfish are not native to New Jersey; in fact, many of our freshwater game fish are introduced species. Channel catfish, or Ictalurus punctatus, were originally found only in the Gulf States and the Mississippi watershed, north to prairie provinces in Canada and south to Mexico. None were present west of the Rockies or on the Atlantic Coastal Plain. But as the most commercially grown and harvested freshwater species in the U.S., they have been widely introduced throughout the United States and the rest of the world.

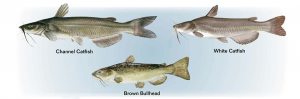

The catfish “cat” earns its popular name from the whiskers or barbels around its face. As far as catfish go, the channel is the best looking, with its spotted sides and a forked tail. In New Jersey’s Delaware Estuary we have primarily two other North American cats—the New Jersey native white catfish and the non-native brown bullhead. To be clear all three are indigenous to North America, but the white is also native to New Jersey.

Channel are the largest of these catfish with a record catch of 58 lbs. taken in South Carolina. New Jersey resident Howard Hudson holds our state’s record of 33.3 pounds, landed in Lake Hopatcong. However, most channel cats that are caught on line are about two or three pounds. A one-pound catfish in the wild is between two and four years old, and a Missouri study indicated that a 13-inch cat was on average eight years old. When commercially grown, most are harvested at two years of age and will weigh in at 1.25 pounds. But know that commercial fisheries also raise other species that have faster growth rates.

The New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife describes the channel cat as “adaptable;” it is found in clear, warm lakes and moderately large to large rivers on sandy or gravelly bottoms. They specifically call out the Delaware Estuary and its tidal tributaries as New Jersey’s most productive waters for channel cats, particularly the Maurice. The Division lists the Salem and Cooper River Park Lake as having a good fishery as well.

The catfish have a skin vs. scales. Possibly one of the most remarkable facts is that they primarily detect food by taste and their tastebuds are found on the entire external surface. They can also taste with their mouths, but their pharynx, gill arches, and barbels all play a role as well. In clear waters eyesight is also used to find food. They are omnivorous, eating plant material, algae, small fish, crayfish, clams, snails, aquatic insects, small mammals, and yes, even birds (likely unusual). They are also a prey species; we commonly find catfish skulls in ospreys’ nests when we band chicks.

The mating behavior of the various kinds of catfish have similarities and differences. All three species guard the nest: Normally it’s the male. In the case of the brown bullhead the female protects the clutch of eggs at a further radius than the male. Bullheads and white cats both help to make the nesting site, normally under a bank’s overhang, under fallen logs, or near rocks. Channel cats use the same areas, but also they often adapt cavities made by animals such as muskrats or beavers. The male parent that guards the nest also aerates eggs by fanning with its fins. This is to increase oxygen to the eggs, even in cases where dissolved oxygen levels are sufficient. The eggs must be manipulated, sometimes by mouth or fin, but some eggs are eaten by either of the parents. Differences in mating and parental care habits can be found in writings by W.B. Scott and E.J. Crossman.

Threats to catfish productivity and survival include sedimentation caused by soil erosion from banks or in stormwater systems. Construction projects and farms are required to employ erosion controls such as silt fences and vegetated buffers. Proper operation of wastewater treatment plants is necessary to maintain dissolved-oxygen levels. Catfish are somewhat tolerant of low oxygen levels but their prey are not. Channel catfish concentrate contaminants such as heavy metals such that water quality is important within the estuary, not just for catfish but for all living things. In general, many of our fish species contain toxic metals or other contaminants that require warnings to be issued about limiting their consumption. Possibly this is a topic for another article by one of our learned toxicologist CU members.

That being said, we still enjoy eating them on occasion. We used to have an annual catfish fry and I even broke down and bought a fryer, but it seemed so easy to end up with an oily mess or a seemingly unhealthy meal. Recently, my nieces insisted I purchase an air fryer that has made catfish a pleasure to prepare, although I am not in charge of the skinning, which is the most difficult part. I preheat the fryer to 400 degrees, dip the filets in air fryer bread crumbs, and sprinkle with Willie’s Hog Dust, my go-to seasoning. (Okay, I like the name nearly as much as the seasoning.) Place the filets in the single-layer basket of the air fryer and spray with olive oil. Cook three minutes, turn over, spray the top side, and cook two minutes more. Check for flaky consistency and cook another minute if needed. If you buy commercial filets and they are large you would have to experiment with the amount of time, but for a 12 to 15-inch catfish this seems to be sufficient.

If you are fishing for catfish, chicken livers are an especially good bait. Other common enticements are night crawlers, crayfish tails, and hellgrammites (the larval stage of a dobsonfly). We use chicken livers. Since we live on the Maurice we keep a tub or two frozen on hand for when aspiring young anglers come to the house. Don’t forget a fishing license, especially if you’re in freshwater. The freshwater regulatory line in the brackish Maurice is upstream of the confluence with the Manumuskin.

Sources:

Living Resources of the Delaware Estuary (1995), Michael R. Boyer’s contribution.

Southern Regional Aquaculture Center

NJ Division of Fish and Wildlife