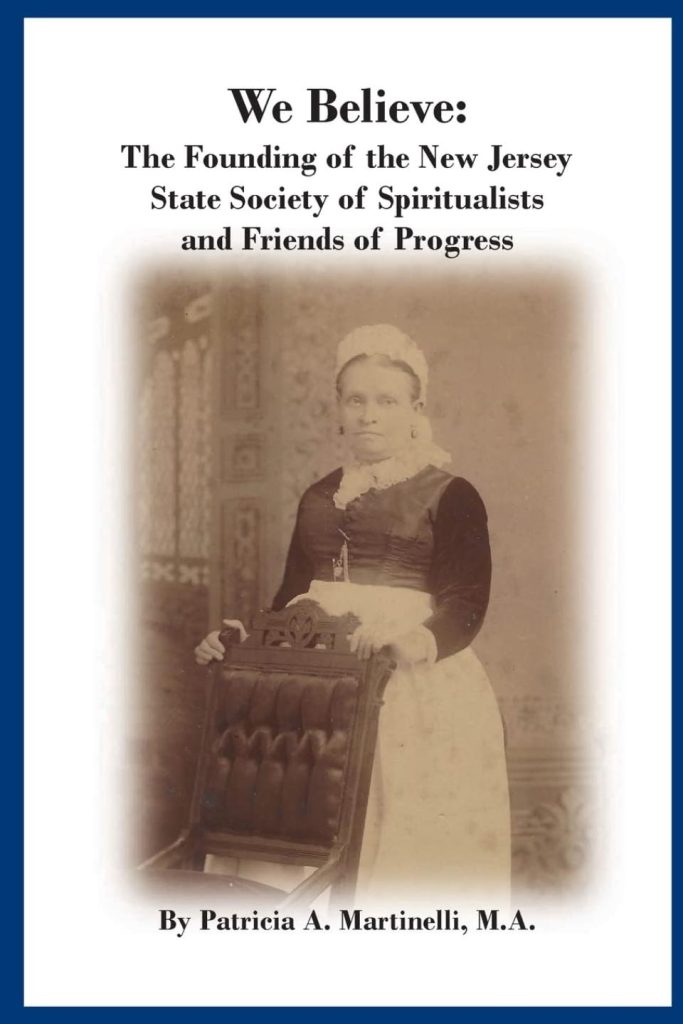

We Believe: The Founding of the New Jersey State Society of Spiritualists and Friends of Progress

Excerpt from a book penned by a local author.

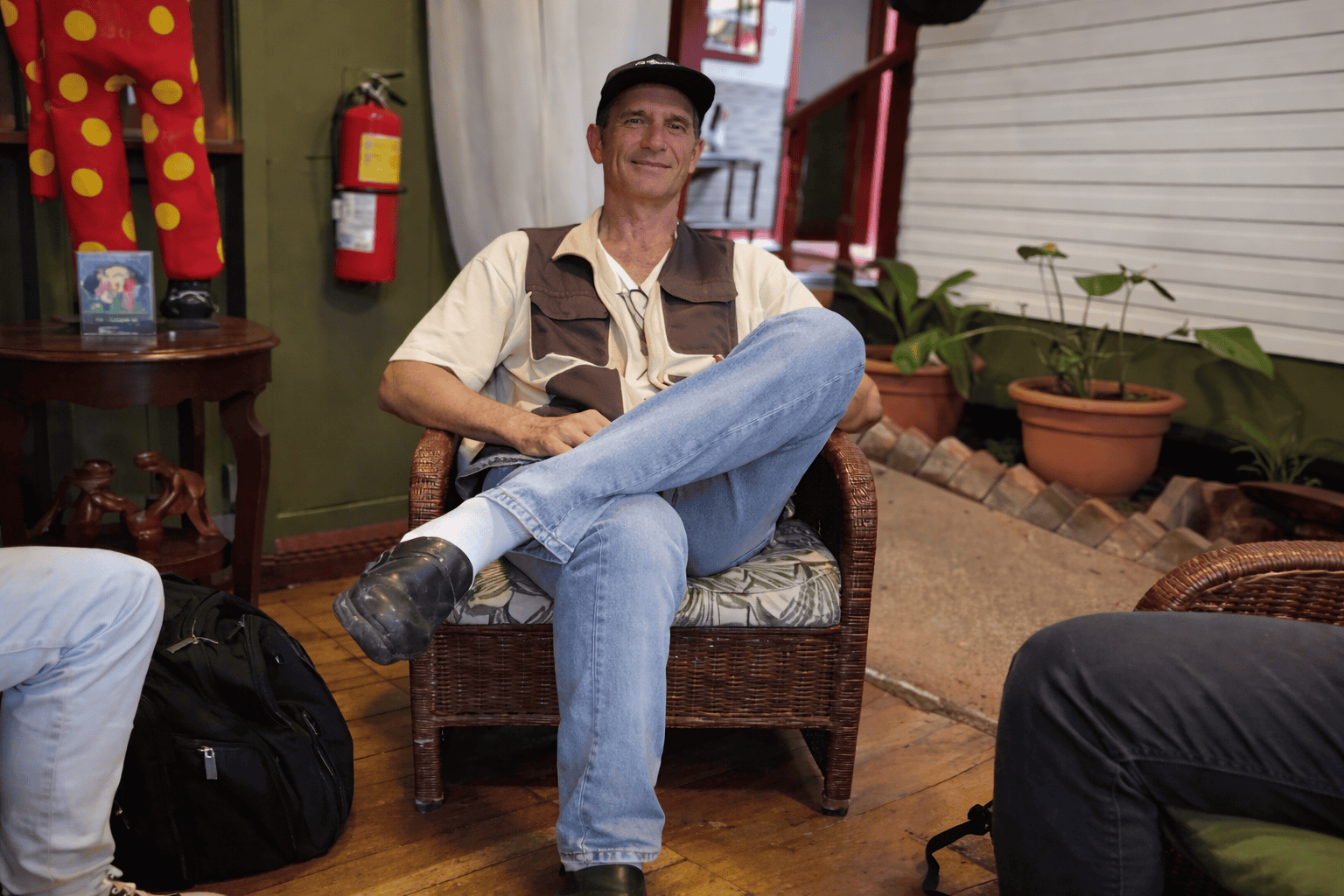

Depending on who you talked to, that fellow named Charles K. Landis was a visionary or a madman; an arrogant capitalist who at the same time wanted nothing more than respect and a fair wage for the average working person. At the same time, he wasn’t above skirting the law when it helped him close another land deal. After all, look what had happened in Elwood. Who ever heard of selling someone property without giving them access to the trees that grew on it? How were the settlers supposed to build their homes and farm buildings without lumber? Landis did, though, and got away with it—later moving on to establish Hammonton with a new partner named Richard Byrnes just a couple of miles down the road. They parted ways a few years later, when Landis decided to strike out on his own and found Vineland.

All of what was said and more about Landis was probably true and his personality seemed to reflect the quixotic, restless temperament of America in the second half of the 19th century. After obtaining a law degree before he was twenty-one, his interests soon turned to real estate speculation. His advertisements promoting Vineland, which flooded newspapers and magazines throughout the United States and Europe, caught the eye of many people who were looking for a place to literally make a fresh start.

Picture a “one horse town” out of any television western from the 1950s and that is a good approximation of what this fledgling South Jersey community looked like in the beginning. Tiny rough-hewn houses, measuring about fourteen by sixteen feet in size dotted the broad main street christened, not surprisingly, Landis Avenue. The impressive thoroughfare was quickly lined with larger homes and essential businesses, ranging from boarding houses and restaurants to blacksmiths, laundries and dry good stores.

Known from its earliest days of settlement as a town that respected liberal causes, many local residents had quickly enlisted in the fight for the abolition of slavery and later became passionate believers in women’s suffrage, public education and prison reform. But in the midst of all of the construction and social development, something else was stirring.

February 11, 1866, dawned raw and wet, a day that quickly turned the unpaved streets of the new community to mud. It was then that Vineland residents Dr. L.K. Coonley and Warren Chase had their first meeting with Andrew Jackson Davis and his wife, Mary, to discuss the future of Spiritualism and the creation of a Children’s Progressive Lyceum in Vineland.

During that meeting, it was very likely that they reviewed a plan to bring the state’s believers together at a convention in Vineland. Before too long, a broadside appeared throughout the region, which announced—CONVENTION and EXHIBITION—in large, bold black typeface—a guaranteed way to attract public attention. The notice, which had been printed by the presses of The Vineland Weekly, the town’s first newspaper, went on to offer more detail: “The first State Convention of Spiritualists and Liberalists In New Jersey, will open at Plum St. Hall, Vineland, On Thursday, May 24, 1866, At one o’clock P.M. and continue two days. The object of this meeting is to effect a State Organization to cooperate with the National Organization of Spiritualists in furtherance of the objects recommended.”

Vineland native Patricia A. Martinelli is the author of 12 books on regional history, including the one excerpted here, We Believe: The Founding of the State Society of Spiritualists and Friends of Progress. Her books are available for sale through amazon.com, lulu.com and Barnes & Noble.