Vineland Pioneer

Susan Fowler was an outspoken supporter of social causes.

In November 1868, a suffrage protest drew 172 Vineland women to the town’s Union Hall where they symbolically voted in the first presidential election after the Civil War. Although their votes could not be legally counted, the action sent a shock wave throughout America since it was the first time so many women had participated in such an event.

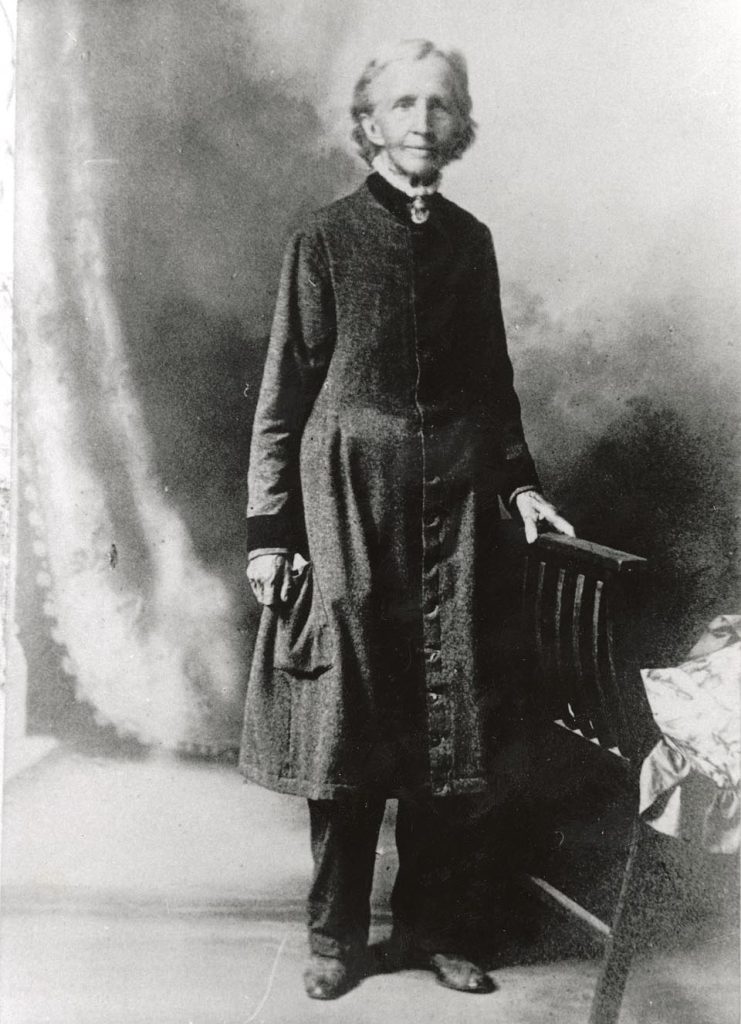

One of those women was Susan Pecker Fowler, a slender figure clad in the “reform dress.” Her everyday outfit consisted of a pair of trousers and a long jacket that ended below the hips. Gone was the long sweeping skirt that was still worn even by the most ardent of suffragists. And, more importantly, gone was the restrictive whalebone corset that caused damage to women’s internal organs because of its tight laces.

At 45, Fowler was one of the Vineland Pioneers who was attracted by the promise of the fledgling community. She had left her family in New England to settle where new ideas were not just passionately discussed but actively supported. Vineland’s liberal climate had already achieved national notice just a few short years after the town was founded in 1861.

Fowler, born on May 31, 1823, in Salisbury, Massachusetts, was the oldest of three children. She later became a teacher, who adopted the scandalous new reform dress at 28 because she believed it was time for women to escape from the tyranny of fashion. For five years, she owned a business in Amesbury, Massachusetts, but bought a five-acre farm after moving to Vineland.

She quickly became an outspoken supporter of social causes, including the Vineland Anti-Fashion Society and the New Jersey Society of Spiritualists and Friends of Progress. In addition, Fowler served as corresponding secretary of the Camden County Woman Suffrage Association, secretary of the New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association and was a leader of the Vineland Grange.

Like Mary Tillotson, another Vineland resident who was prominent in both the suffrage and dress reform movements, Fowler participated in the first state convention for universal suffrage that was held in Vineland in November 1867. The following year, she was among those who cast their symbolic ballots at the Union Hall.

Fowler frequently wrote letters to the editors of newspapers throughout the United States, urging support for suffrage. In her opinion, it was heinous that the law accepted tax money from women but refused to give them a voice in government. She considered “taxation without representation” to be nothing less than robbery.

Despite the demands of her various interests, she successfully ran her own farm and sold the produce at market for close to 30 years. Fowler remained single in order not to relinquish her property to the control of a husband, which would have then been required by law.

However, the physical demands of farming eventually took their toll. Although she declared marriage was “legalized immorality” that no woman of “advanced thought” would choose, she reportedly began to make plans to marry when she turned 80. Apparently, the years of hard labor on the farm had finally started to catch up with her.

In 1904, after corresponding with a 46-year-old man from Minnesota named George Edward Fowler, she announced that she was engaged. Fowler began to sew her own trousseau in preparation for her wedding while her future husband sailed to England reportedly after receiving word of his father’s death there. Despite her plans to proceed with the ceremony, her fiancé apparently never returned. According to the 1910 census records, Fowler’s status remained listed as “single” until her death at home on April 30, 1911. She was buried in Vineland in Oak Hill Cemetery.