TIME CAPSULE: Museum of Native American Artifacts at Bridgeton Public Library is a Cumberland County Treasure

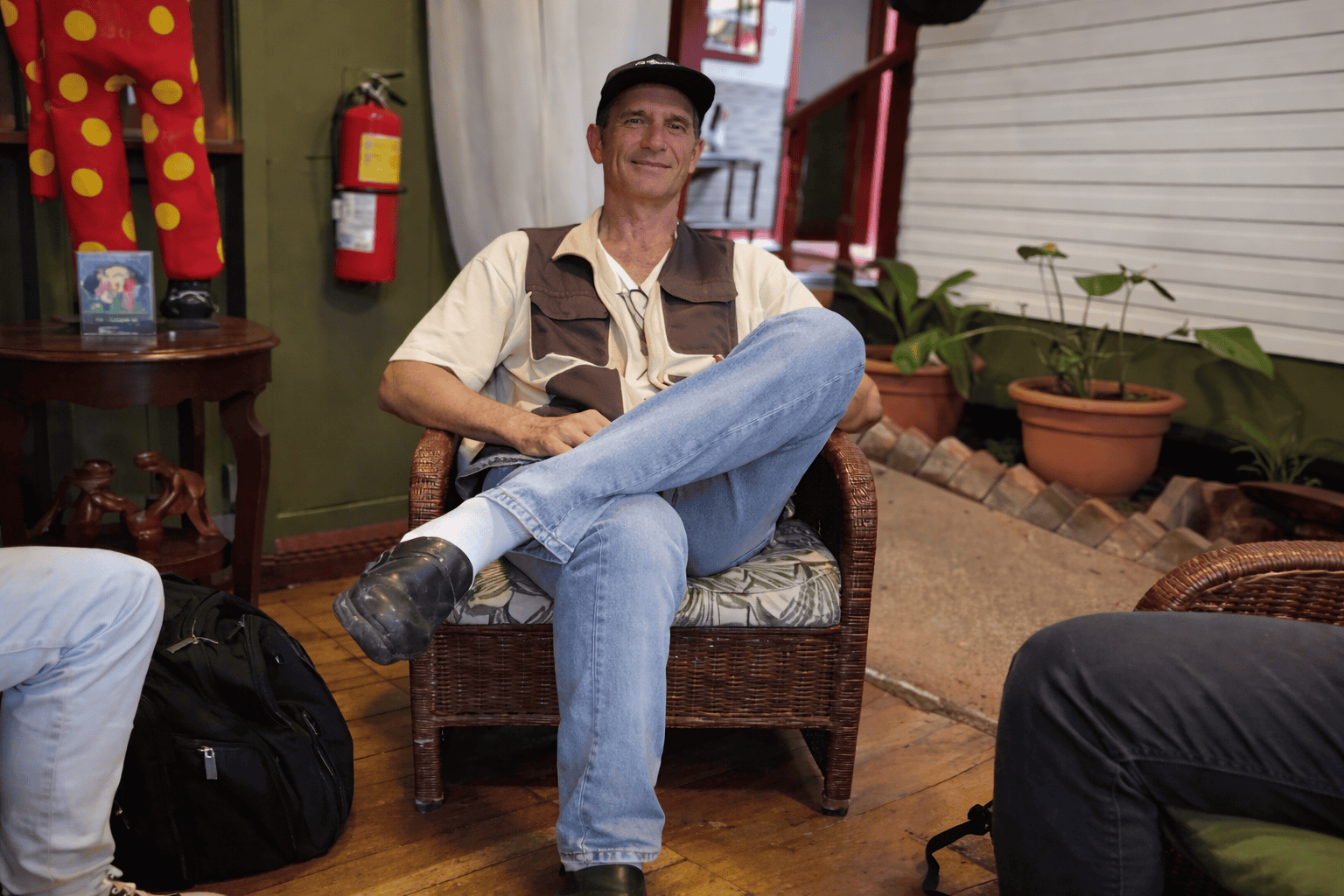

Experts who have visited the museum’s collection—including Therman Madeira, an aficionado in Lenape artifacts—believe the assemblage to be the finest and most extensive of its kind. PHOTOS BY AUTHOR

For those of us who relish going outdoors the heat has been a bit of a deterrent. Besides escaping to our shore’s beaches, or a wet paddle, I’d like to suggest an indoor activity that might prepare you for an additional element to be aware of during your outdoor explorations.

My husband and I built our home on the shores of the Maurice River more than 40 years ago. While clearing our property for construction and digging our foundation, we would occasionally find a Native American point or piece of pottery. While working in the garden, on rare occasions I will still unearth what is commonly called an Indian arrowhead. We became curious about those who inhabited the river shores many generations before we did, even before the colonial inhabitants—those known as the Lenape tribe, also called the Delawares by the colonists.

We took an adult education archeology class to learn more. We discovered that surface hunting for artifacts is considered ethical but digging for relics is frowned upon, and may even be illegal. The reasoning is that when a person digs for evidence of Native American presence the artifacts are no longer in their original placement (in situ), and placement is key to context and to learning about the date and circumstances of the object’s manufacture.

When archeologists try to make conclusions or inferences about past uses of implements, objects found in close proximity often offer a greater understanding. Everything is a puzzle piece that helps to illuminate the lifestyles and stories of the past. Also, discoveries and constantly improving technology offer tools that refine clues to an even greater extent.

When I was growing up it wasn’t unusual for youngsters, especially Boy Scouts, to take an interest in looking for fragmentary evidence of early Americans. The pastime was especially popular in the 1800s to mid 1900s. It was not uncommon for people to display arrowheads in a frame backed by unbleached muslin. Some folks even crafted art from arrowheads (offering little historical significance or context). Collections that were assembled were often passed on through generations or gifted to museums.

George J. Woodruff’s portrait greets visitors to the Bridgeton Library’s Museum of Native American Artifacts. From boyhood until his death in 1969, he collected, assembled, and interpreted implements used by the Lenape Tribe. He kept logs of the collection, noting the origin of each piece and whether it was donated, purchased, or his own discovery. Each piece is numbered and cross-referenced to a log entry.

Sometimes on our CU Maurice River walks a participant will ask about a shard or stone and want me to examine it to see if I think it has Native American origins. Even if the fad of collecting has faded, an interest persists in those early people who walked the trail before us, and that curiosity adds spice to the outdoor experience. So how can you learn more?

In our region one of the finest collections of Lenape artifacts is displayed at the Bridgeton Public Library, amassed by George J. Woodruff (1904–1969). He found his first “arrowhead” on his father’s farm when he was 10 years old, while picking chestnuts off the ground. His collection represents 55 years of ardent accumulation.

Archeologists generally call arrowheads “points” because not all of them were used on shafts as arrows; they could be spears, knives, or other implements. Points often date back to Stone Age times. Among the oldest are some of the least primitive or most finely crafted. So age is not directly correlated to degree of wear or fineness of workmanship. Generations of tribes might even make use of older points that were expertly fashioned.

A popular hobbyist technique for finding points is to search for them in recently plowed farm fields after a rainstorm, especially near the banks of a river where Native Americans would find plentiful animals and plants to provide sustenance. A river offers transportation and fishing opportunities as well. After rain, the surface of artifacts will often be washed, making them easier to spot.

This group of shards or potsherds consists of fragments of clay vessels. Many are embossed and decorated by corn cobs, twine, or other objects. They derive from the Archaic Period: 2,000 B.C. to 1,000 B.C. The potsherd on the middle left has a hole drilled in it, thought to be an effort to tie together the pieces of a valuable but broken pottery vessel so that even though it could no longer hold liquids it could be used to cook solid foods. All objects in the museum were found within a 30-mile radius of Woodruff’s homestead.

Native Americans’ lives were ruled by the turning of the year in terms of sustenance. Rivers were fished when certain species spawned, plantings were dictated by the season, and wild game was hunted especially during migrations. Winters required below-ground storage of root vegetables.

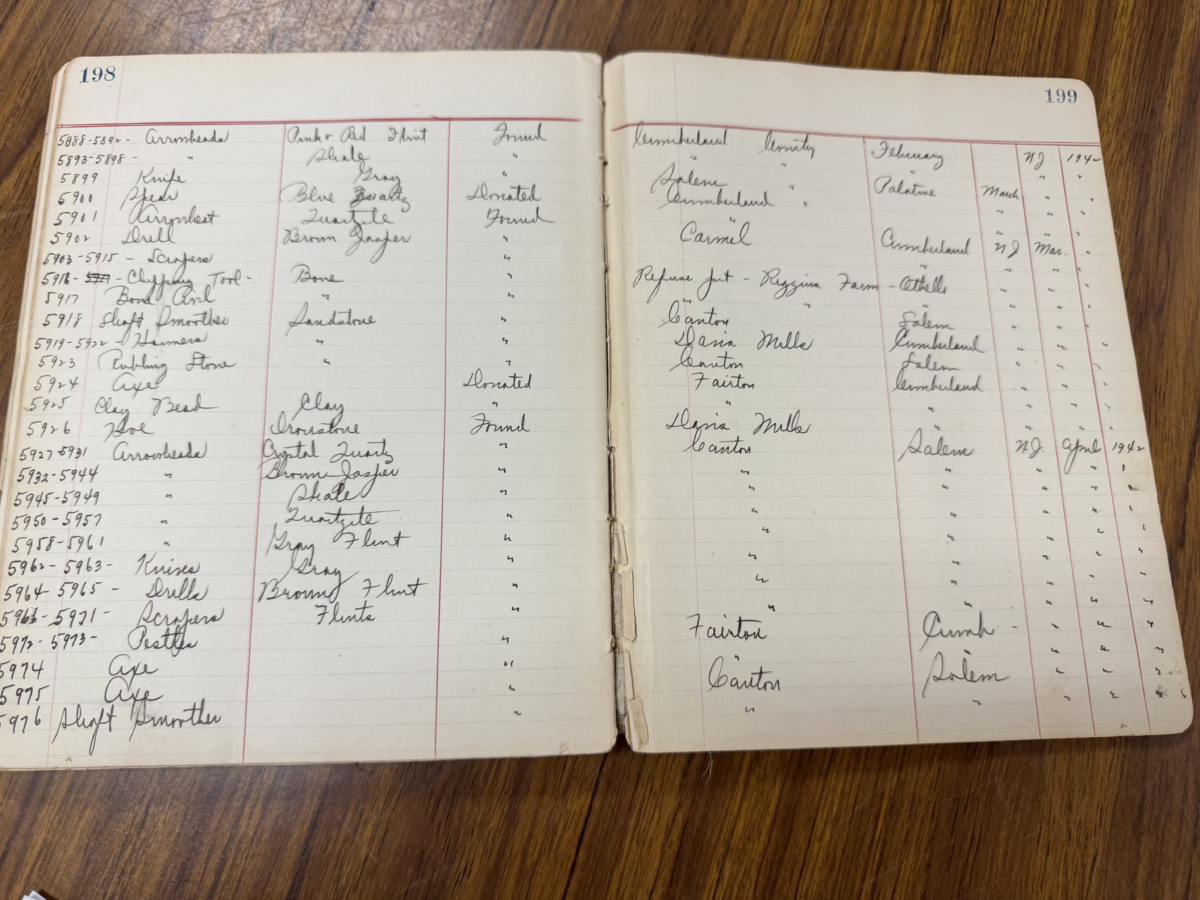

Woodruff was meticulous in documenting his finds. He kept a record of each item with the date, location, and some notes describing the artifact. Over his lifetimehe collected at least 30,000 implements, all originating within a 30-mile radius of his home.

I had the pleasure of visiting with Adaria Armstrong, the library’s director of youth services. She considers it a great honor for the library to host the extensive collection. She shared one of Woodruff’s log books with me in which an “arrowhead” made of quartz was donated to Woodruff in October 1911. The book seems to indicate that his logging of artifacts began when he was 13 years old. The book’s second entry shows a date of 1917 for article number 1 and ends in 1942 with an item numbered 5976 on page 199. This was but one log representing a fragment of the data he compiled. Each piece shows the place of discovery; some were given to him and others were found by Woodruff.

A few years after his death his wife and sons donated the collection to the City of Bridgeton. Then in July 1976, after much preparation, Bridgeton Library opened the George J. Woodruff Museum of Native American Artifacts.

Over her six years in Bridgeton Armstrong has given dozens of tours through the museum to first through 12th grade students. They have some “please-touch” items that allow a visitor to hold something fashioned and held by Native Americans thousands of years ago. Some artifacts of note are Folsom points that were created 10,000 years ago; other points are made of iron stones that date back between 5,000 and 8,000 years.

These three-quarter grooved axes are just a sample of the number of items displayed in the museum.

Also on display is an assortment of clay pipes, shaft smoothers, net sinkers, axe heads, and drill points representing finds dated from 500 B.C. to 500 A.D. Other artifacts exhibited are mortars and pestles likely used to grind grains, herbs, roots, fruits, and seeds into flours. These were developed during the Middle Archaic Period, 5,000 B.C. to 2,000 B.C., as are “bannerstones.”

The purposes of bannerstones remain unclear. Archeologists know they originated in the Archaic Period and were found primarily in the eastern woodlands of North America. Experts theorize that they were used in conjunction with an atlatl, a device for hurling spears farther. But because of their meticulous detail they are thought to have ceremonial significance as well. There are 24 different shapes of bannerstones, most of them formed out of river-worn round stones.

Generally bannerstones are three to five inches in width, with a hole drilled in the center. The stone is believed to have been hollowed out by rotating a river reed between the palms. It is no surprise that some museums have displayed them almost solely for their artistic merit (Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Many pottery shards were painstakingly reassembled by Howard Radcliffe. He pieced together over 57 pots. One pot required approximately eight hours of labor a day for four weeks to complete.

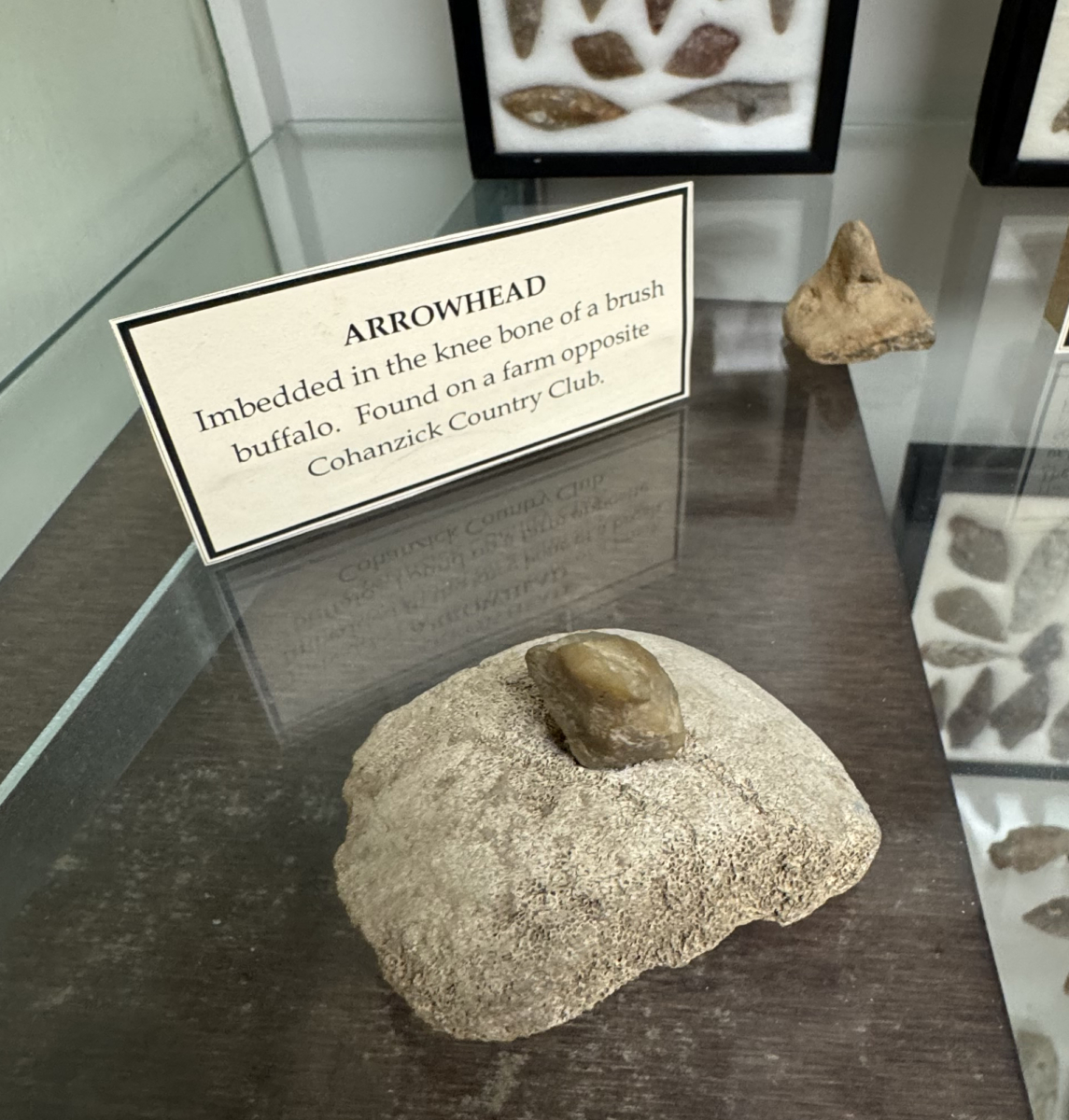

Hunting implements make up a significant amount of what is on view. There are objects called gravers. These originate from the Big Game Period, 10,000 B.C. to 8,000 B.C. The museum’s most unusual artifact is a point embedded in a bison’s kneecap—found on a farm opposite the Cohanzick Country Club.

George Woodruff’s artist friend Howard Radcliffe shared an interest in Native Americans. He reassembled more than 57 pots from shards of shattered vessels. Imagine a rounded jigsaw puzzle with missing pieces. One displayed pot’s signage gives us insight into this labor of love: “Found in 693 pieces. It required 8 hours a day for 4 weeks or 160 hours to assemble.” Armstrong considers this dedication to be one of the most remarkable aspects of the museum. She says visitors “just marvel at the expansive collection.”

Cumberland County’s Explore Cumberland County website states that Radcliffe was “known in South Jersey as the ‘Grandfather’ of all local Indian artifact collectors.”

In an article penned by Woodruff in 1957, he says that signs of Native American occupation were becoming more scarce because of more modern farm machinery “that not only pulverizes the soil but the stone relics as well.” He went on to write that scarcity was increased by “the hundreds of collectors who roam the fields and dig in the woods the year around, adding to their private collections.”

This relic is one of the museum’s most unusual artifacts. It is a point embedded in the knee bone of a brush buffalo. It was found in a farm across from where Cohanzick Country Club was situated, now a Wildlife Management Area.

Woodruff’s wife shared his passion and they both recognized the need for preservation, exhibition, and study. It is ironic that his assemblage removed the artifacts from a great many places, but with the development of roads and structures it also gives us great insight into the past, all because his wife and son saw the wisdom in donating the collection to the Bridgeton Free Public Library. Now all we need is the wisdom to appreciate it.

Sources

Explore Cumberland County NJ.com

Woodruff Museum of Indian Artifacts.

Bannerstones: Ancient Indigenous Stone Carvings, North America (6000–1000 BCE, Anna Blume, February 18, 2025

National Part Service, “Arrows, Guns and Buffalo,” by Dana Dick

BRIDGETON PUBLIC LIBRARY

150 E. Commerce St., Bridgeton, NJ 08302

Tuesday and Wednesday 9:30 a.m.–7:45 p.m.

Thursday and Friday 9 a.m.–7:45 p.m.

Saturday 9 a.m.–3:45 p.m.

Closed Sundays and Mondays

To visit the museum’s collection, call 856-451-2620.

MEET ADARIA ARMSTRONG

Adaria Armstrong began her tenure at Bridgeton Public Library in July 2019. Prior to that she worked at Leonia, Englewood, and Maywood libraries in Bergen County, beginning in 2014.

She holds an undergraduate degree in Sociology and Anthropology / Environmental Studies minor from Stockton, a Master’s degree in Social and Cultural Anthropology/Environmental Sustainability track from California Institute for Integral Studies, and a Master’s degree in Library and Information Science from Wayne State University in Detroit, graduating Magna Cum Laude in May 2019.

Adaria Armstrong, the Library’s director of youth services, examines some “please touch” items that allow visitors to handle artifacts from the Lenape culture.