The Wild Ones

Conservation efforts have enabled the return of wild turkey to New Jersey woodlands.

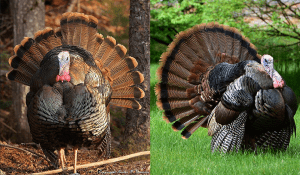

Each spring for 32 years I have been hunting wild turkeys. And every spring a few turkeys will make a turkey out of me; some would say that is not a very big lift. Watching turkeys in the spring is a true marvel as the males put on their displays for the females. The control they have over their plumage is remarkable, and when the gobbler fans his tail he is nothing short of spectacular—wow! The head of the aroused male will display shades of red, blue, and even white, such that he really struts some All-American swag. It’s a great lead-in to our All-American celebration of harvest—Thanksgiving.

Hunters use a number of different calls to imitate a female in an effort to lure in a male turkey. However, this is not really a natural state of affairs. It is the male who calls, and then fans his tail, in an effort to attract a female, so a hunter’s calls make him wary. The hunter that over-calls is likely to drive a turkey away rather than entice him to come investigate. Often a female will show up before the gobbler, being interested in defending her territory from unfamiliar creatures.

On a number of occasions I have found myself surrounded by hens. If you move a muscle the gig is up; a hen will let out a “put call,” warning the woods’ inhabitants that an intruder is present, thus ending your chances of seeing a male.

Adult male and female flocks will interact a lot in the spring. Jakes, or juvenile males, generally hang together travelling in small bands. In a field you might see congregations of all-aged flocks. Holding little status in the pecking order, jakes generally maintain a low profile, staying respectful distances from the mating rituals of adult birds and from adult male fights.

Once, from just behind a berm of dirt, I watched two fighting male turkeys surrounded by females. The turkeys were so mesmerized by their battle that they didn’t notice me. The opponents snapped their wings like Spanish women’s fans. Their wings were spread and closed repeatedly and their large spurs were thrust about in an effort to attain dominance; the victor gets the dames! The females were talking it up, clearly excited by the entire event. When they finally noticed me it was if someone had rang a bell ringside. They froze, drew their feathers closely into their bodies, and in an instant were gone, as though it had all been a mirage.

People will often tell me, “Come to my backyard; the turkeys aren’t even concerned about me.” The inference is that I couldn’t catch fish in a fishbowl, and that turkey hunting is a cinch. In their yard and for them that may be true, but in general those people are doing things the birds observe them doing each day—filling a birdfeeder, getting into their car, taking out the trash, or whatever.

One day when I was hunting, a farmer’s wife, about 1,000 feet away, was hanging laundry with a huge gobbler displaying right next to her. My call had no effect, so I guess she had the right stuff. Yes, they know our routines. If she had sat at the bottom of a tree in camouflage and waited for him to come within 30 feet of her, he would probably have exited.

Also, in a housing development, turkeys expect to see people in the ’hood, but in the woods things change. Many forest birds have never been in a neighborhood, or rarely see people except for farmers focusing on their chores.

With Thanksgiving upon us, what are the turkeys doing? They are not courting but rather determining pecking order. This time of year the flocks are normally separated by sex. Females often have their most recent brood in tow. By Thanksgiving their size difference is barely noticeable, with the exception of late broods who look slightly smaller than their mothers.

Their main activity is browsing for forest mast—berries, nuts, acorns, pinecones, and various other seeds and fruits. They also eat snails, worms and other invertebrates, and loose corn and such from farmers’ harvests. They are known to consume small reptiles as well, but those might be in short supply during the colder months. They often make a lot of noise kicking up dead leaves scratching for food, but they can move through the woods silently when they sense danger.

Similar to some other terrestrial species, such as quail, pheasants, partridge, grouse, and woodcock, they stay primarily on the ground, which gives them powerful leg muscles. They can run 20 to 25 miles an hour. The advantage of hanging out in flocks is the many watchful eyes. If two birds are foraging, studies concluded that 3/4 of the time one or the other is observing for possible threats, but when four birds are involved at least one of the birds is watching 99.9 percent of the time. There are other complexities at play in larger groups but the key principle remains the same: More eyes offer better early warning systems.

While flocks have their advantages they can also attract more attention. Being a solitary bird can be less obvious, and camouflage, cover, and swift flight are a defense employed by many species of birds.

Being on the periphery of an assembled flock versus more centrally located makes an individual more vulnerable to assault. Turkeys are capable flyers and can reach up to 50 miles per hour once they get their body mass moving. But weighing 8 to 23 pounds makes both takeoff and landing a weaker suit. So evading stealthily on foot is their first inclination when threatened. At night turkeys roost in trees as another means of defense from ground predators.

I really enjoy observing flocks of turkeys. They were nearly extirpated from most of North America about 35 years ago, and as a child I never saw one. Today, while many people take them for granted, I do not. I’m grateful for the conservation efforts by National Wild Turkey Federation and New Jersey Fish and Wildlife that have enabled recovery of this species. So in keeping with the Thanksgiving season, “Thank you for your hard-won efforts!”

For More: To learn more about turkey natural history and changing head colors see our previous story “Let’s Talk Turkey and A Turkey Tale” www.cumauriceriver.org/education/nature-around-us/