Sky Dancers

A sure sign of spring in overlapping habitats along the Delaware Bayshore is the American woodcock putting on its courtship display.

When I think of March I think spring teaser. The Old Farmer’s Almanac describes this month as “In like a lion, out like a lamb.” In southern New Jersey it is a bit more of a rollercoaster ride. Cloud cover gives way to a sunny blue sky—that turns swiftly back to winter’s bleakness. Sometimes we get a number of warm days in a row—a preview of spring.

If we have some evenings that exceed 50° F., we may get treated to a much-talked-about, little-seen courtship display—what American naturalist Aldo Leopold described as a “sky dance,” performed by a woodland bird called the American woodcock. Unlike their shoreline cousins—the Wilson snipes, red knots, sandpipers, and the like—woodcock prefer swampy borders, shrubby fields, and woodland edges.

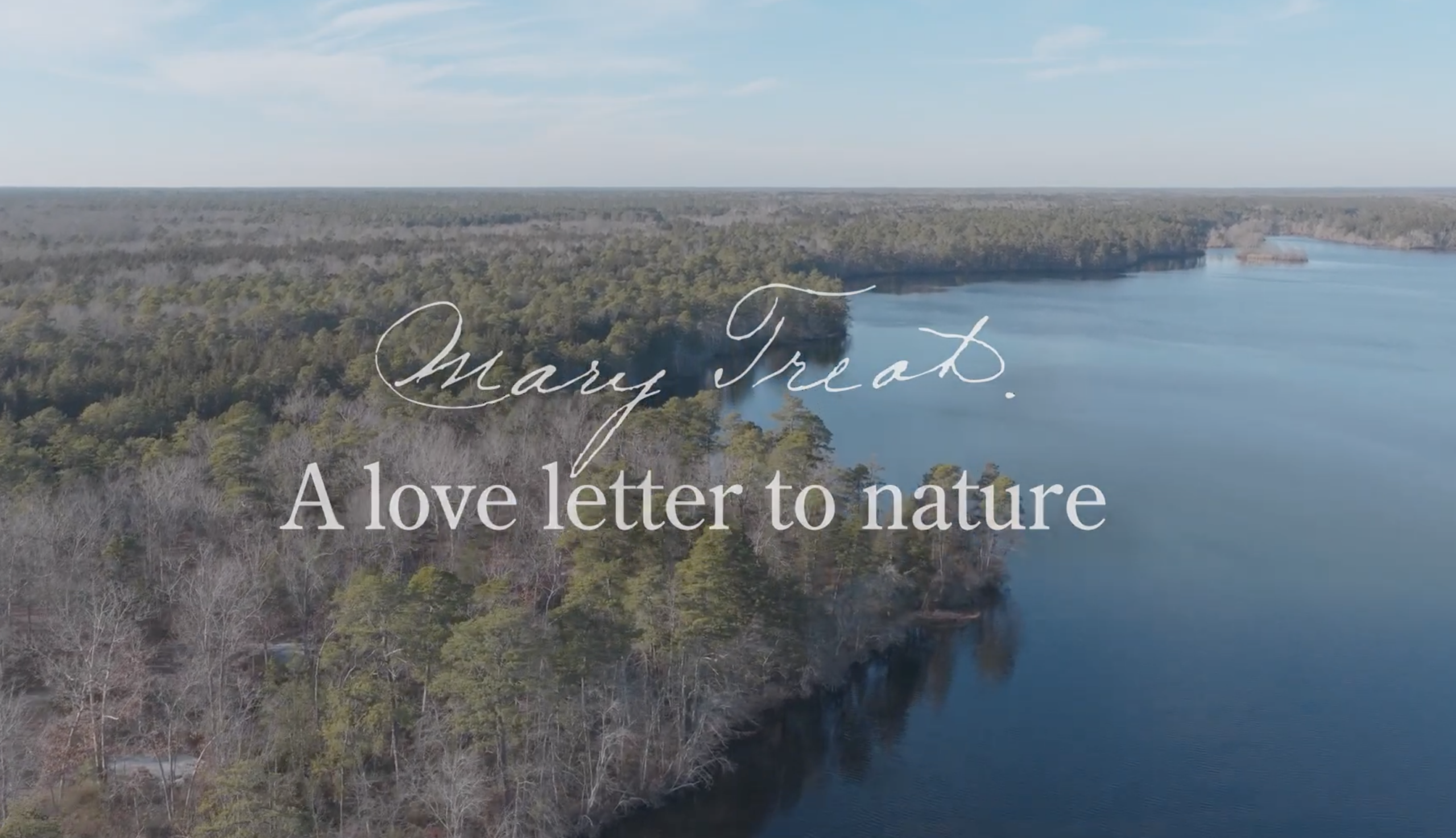

In recent articles, I described ecotones as areas where different habitats meet or overlap, and that many animals seek these spaces. The woodcock is especially fond of places where forests, wetland, and fields are in close proximity to one another. The southern New Jersey Delaware Bayshore wetlands, swamps, and forested borders, which offer a lot of interfacing habitats, are highly desirable to these birds.

Open fields along wooded swamps are a hotspot for woodcock courtship flights. Their “sky dance” begins at dusk, with a male making “peent” calls to attract a female. This is described as a buzzy nasal call. To me it sounds a bit like a mechanical truncated sound, a broken buzz-tone doorbell. On one recording a faint hiccup was noted before each buzz, but had it not been pointed out I would not have noticed it.

After the desired number of “peents” and some dancing, the male takes to the sky in a slow spiral climb that generally goes 200 feet in the air to as high as 350 feet. His wingbeats create a twittering sound, with some rapid whirring chatter, as he makes a near free-fall zigzag and lights back upon the ground.

Then the courtship flight begins again. I’ve not seen the ground dance at night, but what’s described sounds much like the groovy seesawing walk they use when foraging for invertebrates and, primarily, earthworms.

A number of YouTube videos feature this movement as a “Funky American Woodcock,” and indeed it is. Naturally, the videographers can’t resist putting this to music. Envision the bird taking a step, then rocking its body while leaving its head nearly in line with the same spot on the ground. It’s like a porch swing moving with anchored spots—its head and feet—remaining fixed as the body rocks. The birds lift and lower their back and shoulders, a tad analogous to the swing’s seat. Often they take a step forward but at other times stay still. Forward movement is extremely slow and sometimes imperceptible.

There are a few theories about this rocking strut. One is that it allows the bird to sense worms when foraging. Biologist Dr. Bernd Heinrick, professor emeritus at the University of Vermont, suggests that the display saves energy when the birds feel threatened by being observed, rather than exploding off the ground into flight. Possibly he means they simply mesmerize you; honestly, it is nearly hypnotic. Chicks are known to rock-out as young as three or four days old.

I’m not certain what is happening and why, but if you see a woodcock doing its rocky little strut you will not forget it. One day I watched one strut on Maple Avenue in Dividing Creek for nearly 15 minutes while wondering, “What the dickens is this bird about?” And then, “Well, just do what you’re going to do.” Only to find out it was doing just that, simply rocking!

A few weeks ago my husband came home and said, “You’ll never guess what I saw a woodcock doing.” To which I nonchalantly replied, “Uh, rocking.”

“Yes! It was really something to see; he just kept rocking. It was comical.”

Nonetheless, a woodcock is also very capable of explosive flight. They let out a high-pitched doodling call when they take off that is intended to startle you. Whenever I lead a walk and one bursts into the air someone asks, “What the heck was that?” To which I reply, “A woodcock whose nickname is ‘Timberdoodle’ because of the sound they make when taking flight.”

Woodcock are game birds but many a hunter never gets a shot off because of their startle response—exactly as the bird intends. Northern woodcock migrate through and winter in New Jersey, and we also have a year-round population.

New Jersey Fish and Wildlife relays that while woodcock occur across the state, 50 percent of the harvest occurs in Sussex County and 25 percent in Cape May County. This species, like waterfowl, is federally regulated. A hunter is required to have a special federal stamp to hunt and can take up to three birds. This past year the southern New Jersey 2023-24 hunting season was November 11 through December 2 and December 14 through January 2.

Should a hunter recover from the initial surprise, the agile woodcock can navigate its flight through a heavily wooded area at 30 miles an hour! So they can be challenging to take down. Many hunters don’t bother because they taste rather earthy or muddy.

Woodcock can also make impressive migratory flights. Dr. Erik Blomberg, Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Conservation Biology, University of Maine, studies these birds. He found that migrating woodcocks typically travel 870 miles over a month’s time, feeding and resting along the way. But he also recorded that some woodcocks travel hundreds of miles in one night, and one bird was recorded flying 500 miles in a single evening.

Woodcock are especially designed for foraging on earthworms and other invertebrates. They have a long malleable beak that they use to probe in soft dirt. Their eyes are placed high on their head so that when they are probing with their head down their eyes are able to watch for overhead predators. Unfortunately, earthworms absorb contaminants such as cadmium, lead, and pesticides from soils, all of which are then introduced into the woodcocks’ diet when they consume them.

A number of birds use a strategy to protect their young known as a “distraction display.” Woodcocks feign a broken wing to lure predators away from their chicks. A number of ground-nesting birds that have young on the ground will tumble about or drop a wing. Killdeer and shorebirds often employ this ruse as well. I’ve also had two wood ducks successfully distract me from their chicks.

Woodcock are very difficult to spot. They are mottled with striated feathers in varying shades of brown and black, making them amazingly well-camouflaged in leaf litter. They are regular visitors in wooded sections of our yard each fall and winter because we live in appropriate habitat along the Maurice River. I see them because my dogs are specifically bred to detect them and other game birds.

When one of our dogs points and freezes like a statute, generally it will be a woodcock’s scent that has caused its instinctual response. Even with the help of the dog, if the bird is sitting upon an open patch of leaves it takes me some time to distinguish it from the background, and sometimes I still fail to see it. The knowledge that it will make a racket when it takes to flight doesn’t necessarily keep me from being taken aback, much like a child with a Jack-in-the-box; possibly the anticipation makes it all the worse!

And then I will think, “Just as intended—nature’s surprise.”

Resources:

- American Woodcock (Scolopax minor) Migration Ecology in Eastern North America, Compiled by: Alexander Fish, Dr. Erik Blomberg, and Dr. Amber Roth, Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Conservation Biology, The University of Maine

- American Bird Conservancy American Woodcock, abcbirds.org

- 2023-2024 Migratory Bird Season Information and Population Status. New Jersey Fish and Wildlife (NJFW) finalized 2023-24 migratory bird hunting seasons. Dep.nj.gov.

- Seamans, M.E., and R.D. Rau. 2018. American woodcock population status, 2018. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Laurel, Maryland.