Searching for a Cause

Rutgers-Camden scientists search for causes of vaping-related illnesses and deaths.

Rutgers University-Camden researchers are leading an effort to find out what may be causing young people to become sick or die from mysterious vaping-related respiratory illnesses.

“Vaping came onto the scene with very little regulation, very little research behind it, and now, unfortunately, we’re seeing problems that this sort of approach leads to,” says Kimberlee Moran, an associate teaching professor and director of forensics at Rutgers–Camden.

Manufacturers of electronic cigarettes tout the battery-powered devices that heat liquid-based nicotine or cannabis extracts as a safer substitute to traditional cigarettes. However, health concerns about the safety of e-cigarettes are growing as more than 1,000 people in the United States have been sickened and several dozen people have died from vaping-related lung injuries, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Rutgers-Camden researchers plan to examine many aspects of e-cigarettes in their study, including the contents of the vape liquid, the components and construction of the cartridges, and how the cartridges might break down over time.

“We don’t know what they are using to make these cartridges,” says Shavari Fagan, the lead researcher of the project, and a student in the Rutgers-Camden master of science in forensic science (MSFS) program. “We don’t know the solvents they are using to extract the vape oil, and those could be very big factors in why certain illnesses like respiratory issues are happening.”

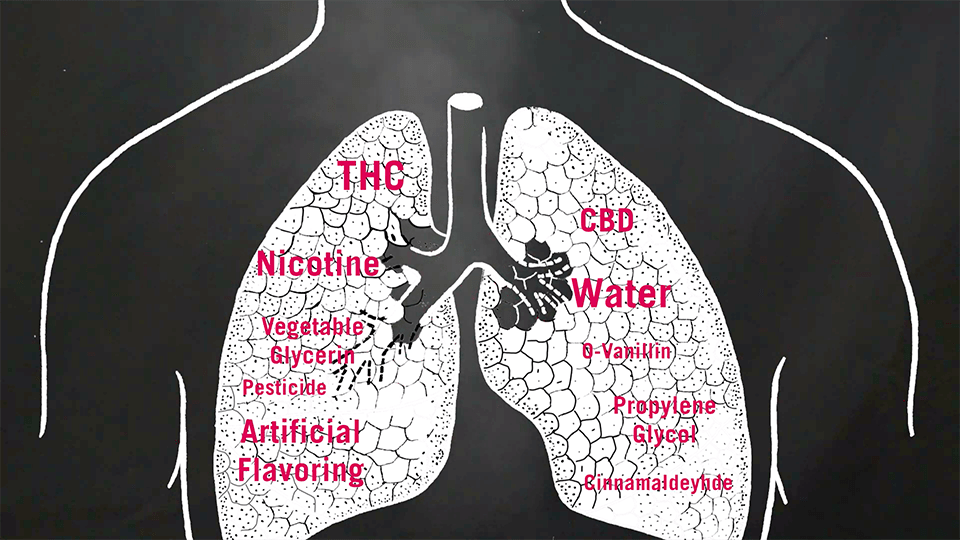

The cannabis vape liquid can contain cannabidiol (CBD), one of two primary cannabinoids that occur naturally in the cannabis plant. CBD, an ingredient in dietary and natural supplements, is nonpsychoactive so it will not get the user high. Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the primary agent responsible for creating the “high” associated with recreational cannabis use.

To conduct studies on the vaping cartridges, the researchers are holding a drive to collect used, empty vape cartridges from Rutgers-Camden students.

Fagan will extract contents of the vape cartridge to examine the oil’s components and check for contaminants, such as vegetable glycerin or propylene glycol, which are solvents used in the extraction of the oil. He says there is a possibility of other components contained in the oil as well, such as pesticides, fungicides, or other microbes in the plants that may have carried over into the vaping oil.

Vaping appeals to many high school and college students because the vape pens come in flavors such as mango, chocolate, and cotton candy. The researchers say the flavorings could have implications as to why the illnesses are occurring.

“If you are vaping a mango-flavored vape juice, you’re inhaling the nicotine, but you’re also delivering the flavoring chemicals directly into your bloodstream, and we have no idea what kind of effect that has,” says Moran.

The vaping-related health issues recently hit home for the Rutgers–Camden research team. After the research project started, a student in the graduate program became sick from vaping and was hospitalized briefly.

“It’s something that we see in the now,” says Moran. “We hope that the research that we’re generating is not only impactful and useful to students, but will generate interest in students as well, maybe to have a better appreciation for the science that goes into the things that they consume on a daily basis, and hopefully leading them to want to be more informed and educated about the things that they put in their bodies.”

The forensic science program’s research is a collaborative effort involving David Salas-de la Cruz, a Rutgers-Camden assistant professor of chemistry; Gene Hall, a Rutgers-New Brunswick chemistry professor; Mary Bridgeman, a clinical associate professor in the Rutgers School of Pharmacy; and local practitioners in the forensic science community from the tristate region, including the New Jersey State Police lab, the Philadelphia Police Department’s office of forensic science, and the Dover Air Force Base Medical Examiner Facility’s special forensic toxicology drug-testing laboratory.

“It’s really exciting to get the opportunity to work on something that is in the news at the moment,” says Moran. “One of the challenges with that is that a lot of people are rushing to fill this space, so how can you fill it in a unique way and answer and address unique research questions? Through our process of collaboration, rather than everybody working separately in their little silos, together, we are going to achieve more.”