Sea Level Rising

Sea level rise and marsh retreat maps out a troubling road ahead for Delaware Bay ecosystems.

The world’s coastlines are in retreat and encroaching on uplands. Delaware Bayshore scientists who study our coastal marshes are concerned by the accelerated rate of their loss. In the 2010’s Dr. Danielle Kreeger, then director of science at the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary, gave multiple presentations about the diminishing marshes of the bay—and how they were disappearing by an acre a day. For the general public this was considered a new concept, possibly even conjecture. Today it is recognized as an irrefutable fact.

Let’s discuss sea level rise and how it is playing out locally. A marsh is a type of wetland, a place where the ground holds water for long periods of time or at least seasonally. Swamps are generally forested wetlands, but coastal wetlands are dominated by grasses and other herbaceous plants while some high marsh may offer islands of trees.

The predominant “native species” in the Delaware Bayshore is salt marsh cordgrass or Spartina alterniflora. The coastal marshes of the Delaware Bayshore were created by an ice age that pushed glacial deposits of sand and other fine soils onto the coastal plain. The nearly flat landscape results in poor drainage and promotes the holding of water on the top layer of mucky soils; sandy soils beneath allow water to percolate through to the aquifer or drain to surface waters.

The marsh is formed when sediments from streams and rivers collect where rivers and oceans meet. Plants take root and hold soils, then die off, creating dead and decaying matter or “detritus” that is decomposed by bacteria and algae. The decaying layers of plants create a top layer of organic soil—muck or peat. Fish, shrimp, crabs, worms, and invertebrates eat the detritus. Microorganisms then consume the feces of these creatures, and this becomes a circle of life, which in turn builds the marsh plain.

The gradual accumulation of layers of decayed matter is called accretion. When accretion is unable to keep up with sea level rise the result is loss of marsh plain—or retreat of the bayfront toward the upland, often to forested areas.

The coastal marsh habitat is considered one of the most productive ecosystems in the world, a place where fisheries are born. The tidal interchange of inundation and draining twice a day washes nutrients over the marsh plain. Think of it as a nursery. Many aquatic creatures need to start their lives in the fresher waters of an estuary rather than the salty ocean waters. They also seek the shelter of grasses to avoid larger predator fish species. Conversely lower tides condense fish into ditches and pools on the marsh plain, making them more vulnerable to be preyed upon by wading birds and mammal species. Surface feeders like skimmers, gulls, and terns make use of this opportunity as well.

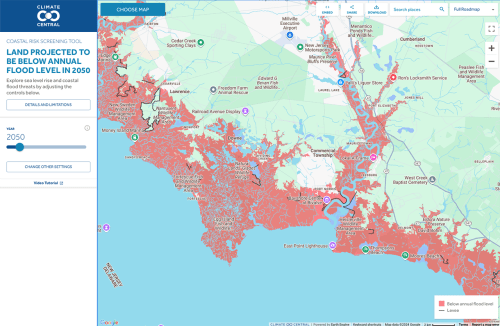

Global warming causes sea levels to rise. Two main factors are at play—the melting of ice sheets and glaciers adding water to the oceans, and water expanding as it warms, called “thermal expansion.” NASA reports that the sea level mean change since 1993 is four inches. NASA, NOAA, U.S. Department of Environmental Protection, Rutgers University, and the U.S. Geological Survey have an online mapping instrument called the Interagency Sea Level Rise Scenario Tool, for which the baseline year is 2000. The data show that waters on the Jersey Coast and Delaware Bayshore rose six inches from 2000 to 2020, and an 3.5-inch difference is anticipated by 2030. On a flat landscape that’s a great deal; added to a full moon flood tide it is even more consequential.

Sea level rise is especially acute in New Jersey. Since the early 1900s waters have risen at the Jersey Shore by 18 inches, more than twice the global mean of 8.0 inches (Rutgers New Jersey Climate Change Resource Center). In addition to climate change New Jersey is affected by a “geologic seesaw, the mid-Atlantic region is subsiding, or sinking, while land to the north once covered by Ice Age glaciers rises up (Rutgers 2020).” The pumping of large amounts of water from aquifers to support communities also adds to the diminishment of New Jersey’s coastline.

Residents’ major concerns are the loss of property, roads, contamination of wells by saltwater intrusion, and in many cases the need to relocate. One farmer told me that he has had to dig his wells deeper in order to access fresh water for his crops.

The Cumberland County coastal towns of Sea Breeze, Bay Point, Thompson’s Beach, Moore’s Beach, and portions of Money Island have already been abandoned. Other beachfront villages have shrunk greatly. The effects of coastal flooding, astronomical tides, storm surges, and hurricanes have been made worse by sea level rise. These events act as a glimpse into a future, where there will be an increased number of such incursions.

As waters migrate further inland there is less buffer between inhabited properties and the advance of the bay. People look to structures to remedy the onslaught of water—seawalls, bulkheads, rip rap, gabions etc. However, human-made barriers impact animals and so do habitat changes caused by rising waters. The forested buffers of the Bayshore are critical for rare and common species of wildlife. Where habitats touch and/or overlap are considered ecotones and these are rich in biodiversity. If one type of habitat is lost, adjacent areas are also negatively impacted. Most animals make use of different habitats, sometimes seasonally or even at particular stages of maturation, so all are important for survival.

Some ecological requirements will match up with retreat and support the existing species while some will not. Beachfronts and marine nurseries can’t creep further inland and still maintain the same available habitats. Beach-nesting birds like skimmers don’t use forested swamp. Horseshoe crabs don’t lay viable eggs in marshy wetland soils or in a dying woodland, but rather on sandy beachfront.

Initially some houses and roads may be raised up, but since people can’t simply back up onto neighboring properties many residents will be forced to relocate. This scenario is going to be played out in coastal communities around the planet and in fact it is already happening.

It is not uncommon to hear Bayshore residents joke that they will soon be living on beachfront property—but they know it is no laughing matter. Access to clean water will require deeper wells. Roadways that once led to villages will be pathways to waterfront, if they even continue to exist.

Politically, addressing global warming is not popular. There was a time when NJ Department of Environmental Protection employees were not allowed to use the words “climate change” or “global warming” in their reports. How do planners plan for the future when politics prohibit speaking about its challenges?

The best outcomes will result from proper emergency preparedness and efforts to curtail greenhouse gases. Some solutions will come from technology. Administrations that support green solution-based economies will have the most positive impacts on reversing global warming. We can’t be sold on a “no change” answer; we must seek innovative solutions. The good news is that scientists have proven global warming to be caused by human activity and therefore the solutions can also lie in human hands.

Sources: Sea Level Rise in New Jersey: Projections and Impacts, Rutgers New Jersey Climate Change Resource Center, May 2020.

Sea level rise and resulting impacts is due to melting ice and thermal expansion and increases the risk. NOAA Climate.gov