History Informs Us

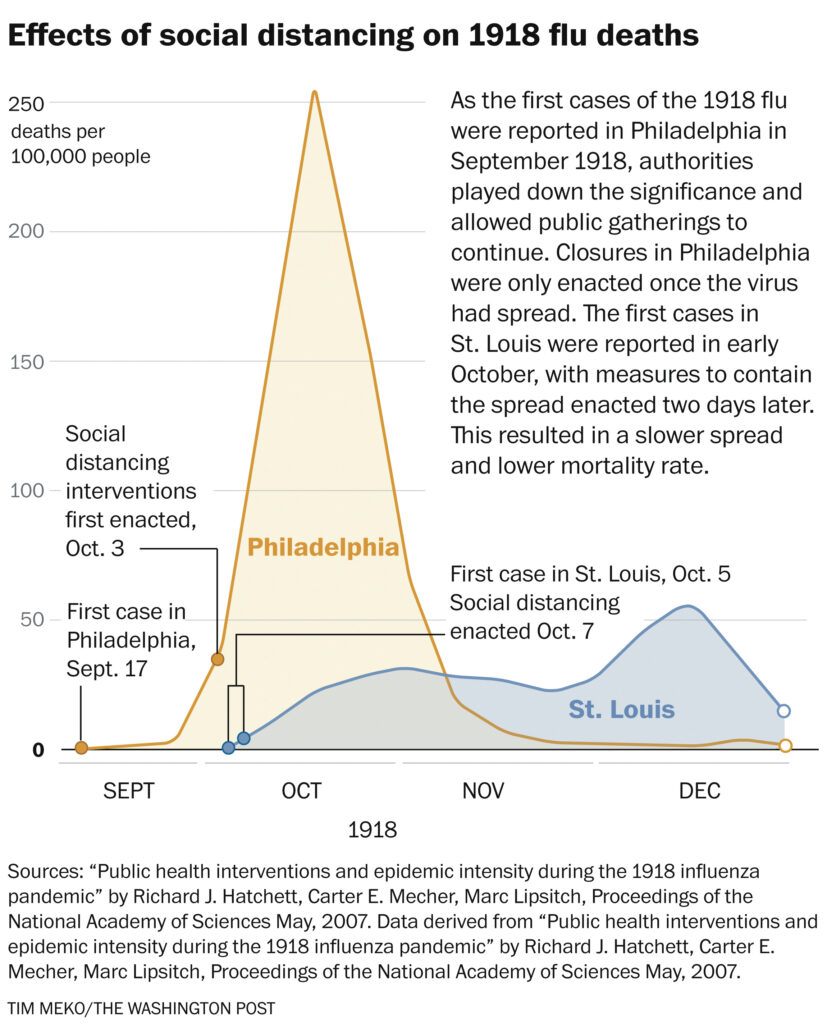

Philadelphia‘s experience with the 1918 influenza pandemic sounds terribly familiar.

With all the inconvenience caused over the past week by the shuttering of eating establishments and curbing of our usual social routines as safeguards against the spread of the coronavirus, perhaps this is a good time to consider the cautionary tale of the 1918 Philadelphia Liberty Loan Parade that took a different approach in the midst of a pandemic.

In 1918, influenza, or Spanish Flu as it was also known, made its appearance as World War I was nearing its end. Attacking the respiratory system, the virus offered little in the way of countering it.

According to the History Channel website, “the most likely origin of the 1918 flu pandemic was a bird or farm animal in the American Midwest. The virus may have traveled among birds, pigs, sheep, moose, bison and elk, eventually mutating into a version that took hold in the human population.”

“The first flu cases were reported in January 1918 among soldiers at Midwestern military posts,” Daniel Patrick Sheehan explained in a Morning Call newspaper article last year. “Some experts believe those cases may have been the worldwide point of origin for the illness, with soldiers carrying the infection to European battlefields.”

By June, the History Channel website says, “the flu seemed to have mostly disappeared from North America, after taking a considerable toll.” But the disappearance was misleading. By August it had returned. Sheehan notes that those who contracted the virus early and recovered “developed immunity that protected them when the flu returned in August…” Everyone else was susceptible.

And this brings us to the Philadelphia parade. The event was part of the Liberty Loan campaign, which encouraged citizens to purchase Liberty Loan bonds to help the government pay for the war. It would not be an exaggeration to say that Philadelphia immersed itself in the effort.

According to The Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP) South Philadelphia Women’s Liberty Loan Committee Records, “Neoclassical statues of winged women were installed throughout the city, both to remind Philadelphians of the loan drives and in some cases to indicate where loan subscriptions could be purchased.”

More than 100 booths were set up throughout the city “to accept subscriptions,” and the Mummers were “involved in public awareness campaigns for the Liberty Loan and participated in publicity events throughout the city.”

Parades were also a part of the promotion, and three had already been held in the city, the most recent on April 6, 1918 during the first wave of the flu. That event managed to avoid any health issues. The next wouldn’t be so fortunate.

The fourth parade was scheduled for September 28. According to a thoroughly researched 2019 phillyvoice.com series by John Kopp and Bob McGovern, “the city had been tasked with raising $259 million for the Philadelphia boys fighting in Europe,” but “the influenza epidemic had reached Philly in early September when a Navy ship from Boston arrived at the [Philadelphia] Navy Yard. By the Liberty Loan parade, 525 people had come down with the illness. Seventy had died.”

According to John M. Barry, historian and author of The Great Influenza, who was interviewed by Kopp and McGovern, “There were multiple letters from physicians not just asking, but demanding, that they cancel that parade.”

But on September 28, the parade proceeded as planned, and an expected crowd of 10,000 turned into a throng of 200,000 in Center City. Within the next two days, more than 600 fell ill.

Three days later, hundreds more were reported sick and fatalities began climbing. The Smithsonian Magazine points out that “with many of the city’s health professionals pressed into military service, Philadelphia was unprepared for this deluge…”

After five days, with hospitals overflowing with patients, the city finally began closing schools, churches, theaters and bars. Kopp and McGovern report that “such drastic action…[was] met with considerable skepticism in Philadelphia. The Inquirer led the charge, accusing city officials of going daft.”

The HSP records identify that, in tallying the results of the fourth Liberty Loan drive which included the infamous parade, “Philadelphia contributed $598,763,650,” more than double the amount it was expected to raise.

Along with that, according to Sheehan, “Philadelphia would emerge with the highest death rate of any American city” during the 1918 influenza epidemic.