Hanging On

American beech holds its leaves through winter, rustling like paper chimes on breezy days—until the spring growth displaces them with new leaves.

It’s fall and I’m all charged up about the changing colors. Locales without seasons would never work for me. Okay, truth be told, in February or March I’m ready for four to seven days of warm weather. But nothing beats fall and spring in the northeast. Clearly I’m not alone in this enthusiasm; people spend upwards of $3 billion annually to enjoy nature’s fall display of colors.

Photosynthesis, or leaves processing chlorophyll to take hydrogen from water and carbon from the atmosphere to create or liberate oxygen, is what makes life on earth possible! Leaves are the lungs of the planet. That’s why the news that the Amazon’s forests are aflame or are being sacrificed for agriculture is so very disconcerting; this also contributes to global warming. We must protect forests because our very survival depends on trees.

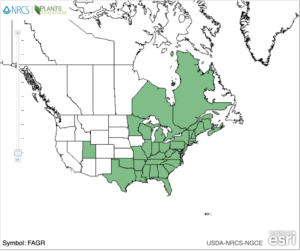

When the chlorophyll returns to the roots we can see the leaves’ true colors, and the drama of fall unfolds. This is a great time to salute the trees for their gifts to us. Some oaks drop their leaves later than other species but the American beech, Fagus grandifolia, wins the deciduous tree competition when it comes to holding on to them.

Most trees have what is known as the abscission layer—a soft spongy spot where the leaf attaches to the branch. This grows over time and eventually pushes the leaf from the branch and sends it to the ground. But the beech does not have the abscission layer; rather it holds its leaves over the winter, and the spring growth then displaces last year’s crop. (Thus, they are a favorite of forestry students who haven’t yet learned to identify the tree by its bark or buds.)

When you walk through the woods in the winter you may notice the coppery-tan leaves of beeches still fluttering from their limbs. Depending on the light they can show an ash-blonde shade that gives them a strikingly lovely appearance. On breezy days the dry leaves on the branches make a crisp sound like the rustle of paper chimes.

Beech trees are considered rather slow-growing; in 20 years some will still be only 13 feet tall. Tolerant of shade, they are normally present in wooded areas that have been established for a few decades, or in what is defined as the final stages of succession. In other words, these spaces transformed to a young forest after some disturbance. Remember that most of our trees were totally harvested during the industrial revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries, when they were turned into charcoal and burned to power all manner of machines. By the early 1900s our forests were gone. So today’s wooded areas generally aren’t over 100 years old, and the forests of the northeastern United States are even newer in tree years.

Logged beech is a long-burning high-quality wood. It is also very malleable when steamed and therefore has been popular for bentwood furniture. In addition it is a popular wood for drums because the tonal qualities lie between maple and birch. Sadly, it is a popular wood for carving graffiti, because the thin bark is unable to heal and markings remain indefinitely.

The beech also produces a nut, although not in great quantity until about 40 years of age. Lots of creatures enjoy this mast—grouse, turkeys, foxes, racoons, white-tail deer, rabbits, squirrels, opossums, pheasants, bear, porcupines, and yes, people. Cornell University professor Jon M. Conrad, who studies economics and management of natural resources, contends that the now-extinct passenger pigeon is linked to the clearing of oak and beech forests.

Now for those of you who like spirits, evidently Beech Leaf Noyau is in vogue with gin fanciers. It involves soaking beech leaves in gin for three weeks and then adding a suggested mixture of sugar, water, and brandy. It is said to be a substitute for sloe gin. Beech leaves are evidently edible and were once used to alleviate rheumatism; possibly what the leaves don’t fix the gin will!

So besides evergreens there is one deciduous tree that keeps its leaves. Each year I appreciate their coppery glory as they declare their stubborn nature, refusing to succumb to the shortened days and that cause their confederates to lose their summer garb.