Get the Kids Outside

We have the means to reverse the trend of a generation losing touch with nature.

Back in 2005 Richard Louv wrote a book that revealed a nation’s youth that is living a life separated from nature. The book was titled Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. It was on the New York Times bestseller list and received the Audubon Medal “for sounding the alarm about the health and societal costs of children’s isolation from the natural world—and for sparking a growing movement to remedy the problem.” It has become an iconic blueprint for natural, environmental, and conservation groups, as well as for educators.

As a child most of my contact with nature was simply through playing in a wooded area by our home or wading in a stream. We would dam a small waterway to make a shallow pool in which to cool off. Our wooded patch was just a quarter mile away, but my eight-year-old legs made it seem at least two miles from home instead. We were unsupervised; we made our own decisions and learned through our successes and blunders. Our play was not planned and organized by adults; it was spontaneous and self-guided. And on weekdays our parents usually dropped us off at school in the morning and we walked a mile home at dismissal. It was the 1960s.

Sure, I was in Girl Scouts and my father was instrumental in introducing me to nature and the out-of-doors. We hiked, fished, paddled, sailed, played catch and tennis, caught butterflies, and more. But I had lots of exploratory time to myself and with my friends. I tasted berries both poisonous and edible, slipped on rocks, climbed trees, made soapbox cars, sailed, paddled, windsurfed, swam in lakes, learned to ride a bike, and lots more. And I want to stress, I did survive to tell of these activities and so did most kids I knew. Life is not guaranteed but it is to be lived.

Between 1970 and 1990 the radius around the home where children were allowed to roam shrank by 90 percent. Today children can identify cartoon characters better than native species of trees, birds, bugs, and mammals. Many studies link the prescribing of antidepressants to computer use, television watching, and lack of time outdoors. People with depression have a higher chance of having a vitamin D deficiency. The best way to prevent this deficiency is diet and adequate sun exposure.

The radius has shrunk because of our being “plugged in” to devices, but also because of fear. In fact the world is not less safe; it is just our perception that it is. Granted, you know your neighborhood better than I do, and pockets of crime exist. I get that. But in general, crime statistics show the world has not become more dangerous. I’m not suggesting reckless abandon, but we need to loosen up.

What Louv labeled as “nature-deficit disorder” is not a specific medical condition, but rather a description of man’s alienation from nature. His recommended solution, to which many professionals subscribe, is to get children outside. He compiled studies that showed nature to be a powerful combatant of depression, obesity, and attention deficit disorder. This was the first book to cite cutting-edge research that linked contact with the natural environment as essential for healthy childhood development. Immersion in nature builds a healthy physical, emotional, and spiritual character.

Nonprofit groups like the Children and Nature Network were created to get kids outside. Children and Nature Network has a number of adages that express its mindset, like “More green, less screen.” They believe that nature makes kids healthier, happier and smarter. One statement I found especially true was “Kids won’t remember their best day of YouTube.” But they do remember a great out-of-doors experience. Often when I speak to adults about their best school memories a trip beyond the classroom is recalled. Also if you ask someone if they remember a field trip, in my experience everyone does.

During the COVID pandemic, particularly between March 2020 and December 2021, many schools turned to remote learrning, but some remained open and held classes outside. Teachers who relied on teaching didn’t need to make the transition to outdoor learning, but rather advised traditionally taught indoor schools how they could bring learning outside.

Beverly Amico of Waldorf Schools addressed the history of outdoor learning and its foundation in schooling children who were ill. “Learning primarily outdoors in our modern day has its history in mid 20th century Europe—a movement inspired by open-air schools developed in the early 1900s for sick children.” Tuberculosis in particular and then the flu pandemic of 1918 encouraged many educators to take learning outdoors. In fact, the Spanish flu prompted Neil S. MacDonald to write a book promoting the open-air school movement, saying that in much of the U.S. “there is practically no temperature problem and no reason why all schools should not be open-air schools all the year round.”

You don’t need to be sick to benefit from outdoor learning.

Numerous educational resources discuss the benefits of outdoor education for promoting effective learning. The advantages fall into some broad categories—creativity and imagination, improved mood, more physical activity, freedom, and building leadership skills.

Outdoor education is generally experiential, involving hands-on exploration, experimentation, and context. Continually reiterated is the enhancement of mental health and how students generally feel less stress when learning outside.

Students tend to be very reliant on the adults around them and self-reliance is more easily achieved in an outdoor context. Freedom builds self-confidence both physically and mentally.

Many subjects come to life outside and concepts can be given greater meaning. For instance earth sciences, science, physical education, and the arts are all greatly enhanced outdoors. For many students a concept is more fully grasped with either a combination of learning styles or a specific style, whether books, audio visuals, and real-life experiences. A living classroom offers a broad-spectrum approach.

Most importantly students get a better understanding of their “oneness with nature” and how they fit in. By way of example, reading about how a bird achieves flight is vastly different from watching a bird fly in its own environment. Making distinctions between species in a guide is different from applying it to “live” birds in the field. Hearing a bird sing is an experience. When children’s lessons are conducted outdoors, they are given the chance to know nature, not just as an observer, but as a part of it—a participant.

The end game for conservationists like myself is that children enjoy nature; once introduced to it they want to experience it again and again. They ultimately understand that their very own survival is reliant on a healthy environment. They build connections not only with nature but with those who share the world with them, both animal and human. And they advocate for its protection. Most will never achieve this last stage. But they may make wiser personal choices, and that’s a plus for Mother Earth.

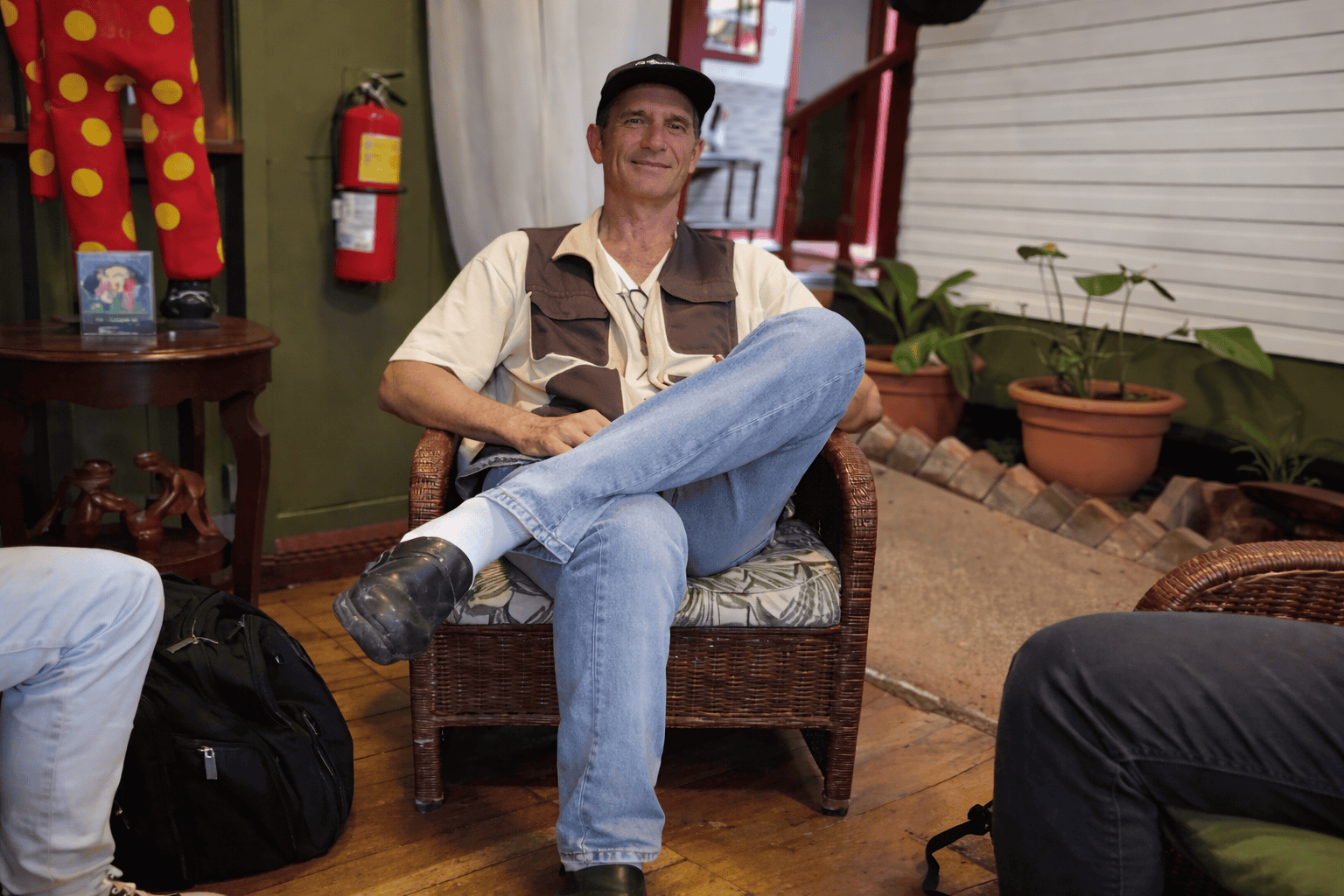

The local nonprofit CU Maurice River offers organized activities to get involved with nature, and they invite you and your family to join them in getting kids outside. Whether you take advantage of their programs or simply hike as a family you will richly benefit from being out-of-doors. n

Sources:

- Waldorf Education, Amidst Pandemic, Waldorf Schools See Resurgence of Outdoor Learning, Beverly Amico.

- When Fears of Tuberculosis Drove an Open-Air School Movement, Intended to curb the spread of tuberculosis, open-air schools grew into a major international movement in the early 1900s, History.com.

- Schools Beat Earlier Plagues with Outdoor Classes. We Should, Too. A century ago, children in New York City attended classes during a pandemic. It seemed to work. Ginia Bellafante, New York Times, July 2020.

- ChildrenandNature.com

Family-Friendly Fridays and More

CU Maurice River offers Family Friendly Fridays; these are programs designed for whole-family enjoyment. All require registration either by calling the office at 856-300-5331 or logging onto the website at cumauriceriver.org and selecting Calendar of Events. Clicking on an item from the calendar will provide you with more information as well as reservation opportunities.

The first three are Family Friendly Fridays:

- Creek Critters

July 19, at 6 p.m.

Prepare to get a close-up look at the creatures living in the waters of the National Wild and Scenic Menantico River. - Astronomy Party

August 23, at 7p.m.

Enjoy learning as a family under the stars at Belleplain State forest. - Map & Compass Orienting

September 20, at 6 p.m.

Grow your exploration skills with fun activities and challenges led by former Boy Scout Leader Gary Moellers.

Also:

- Nature Journaling

Where science, art, and play meet creativity.

Every Wednesday and Thursday in August 8:30–11 a.m.

Registration fee due by July 15. - Dragonfly Sampling

Thursday–Saturday, August 1-3 at 9 a.m.

Visit a Wild and Scenic stream to collect data as part of a national air and habitat quality study. No training required. All ages welcome.

CU Maurice River also offers a selection of walks, most of which are appropriate for youngsters accompanied by a parent or guardian.

Some programs have a cost associated with them. Most are free for members. CU family membership is $30 annually. Membership can also be secured at cumauriceriver.org.